Manual Restraint and Common Compound Administration Routes in Mice and Rats

Summary

Working safely and humanely with research rodents requires a core competency in handling and restraint methods. This article will present the basic principles required to safely handle and effectively administer compounds to mice and rats.

Abstract

Being able to safely and effectively restrain mice and rats is an important part of conducting research. Working confidently and humanely with mice and rats requires a basic competency in handling and restraint methods. This article will present the basic principles required to safely handle animals. One-handed, two-handed, and restraint with specially designed restraint objects will be illustrated. Often, another part of the research or testing use of animals is the effective administration of compounds to mice and rats. Although there are a large number of possible administration routes (limited only by the size and organs of the animal), most are not used regularly in research. This video will illustrate several of the more common routes, including intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and oral gavage. The goal of this article is to expose a viewer unfamiliar with these techniques to basic restraint and substance administration routes. This video does not replace required hands-on training at your facility, but is meant to augment and supplement that training.

Protocol

1. Safe Restraint and Gentle Handling of Animals is a Key Part of Experimental Procedures

- This video is designed to be a supplement to hands-on training provided by your institution.

- Always be sure that IACUC or ethics committee approval is in place before beginning any experimental procedure.

- Each person working on a protocol should know the details of procedures approved for that protocol, and any others on which they are working.

- Approach the rodent with confidence and handle the animals gently, but firmly. Both too- rough handling and tentative approaches may result in bites or scratches to the handler or injuries to the animal.

- When handling animals, there is always the possibility of accidental release or the animal being dropped. Most of these manipulations are best performed over a work surface so that if the animal is dropped or escapes, it is not injured and can be easily recaptured. Follow your institutional policies concerning animals that contact the floor.

- Never handle animals by the tip of the tail, as this may result in a degloving injury of the tail. Be especially careful with large rats or pregnant mice. Always use the other hand to support the body as you lift by the tail.

- Sharp needles work best when giving injections. Although needles for laboratory rodents are sometimes used for multiple injections, this is not advised for a number of reasons, the least of which is that the small gauge often used means that the needles dull quickly.

- Being bitten or scratched is always a possibility when working with animals. If working with a substance or an infectious agent that may cause injuries to humans, take extra precautions, such manipulating animals or agents in fume hoods or biosafety cabinets.

- Gentle approaches and acclimation to handling before attempting a procedure can pay off in animals that are less stressed by handling.

- Practice restraint before attempting compound administration, and practice administering substances to control animals before experimental animals.

- Practicing these techniques regularly instills confidence and confidence results in better handling, less stressed animals, and better scientific results.

- With any handling technique, if the animal is recalcitrant, try a different technique. The animal (and handler) may also benefit from putting the animal back in the cage and trying again later.

2. Manual Restraint

- One-handed mouse restraint

- Lift a mouse by the base of the tail and place it on the cage lid, wire bar cage top, or a similar rough surface.

- One handed mouse restraint is usually performed with the non-dominant hand, leaving the dominant hand free for use.

- An alternative method allows the technician to use their lab coat or uniform sleeve covering the forearm to position the animal prior to restraint.

- Tuck the base of the tail between the 3rd and 4th finger, while gently pulling back on the tail. This will cause the mouse to grasp the surface with all four paws and pull forward.

- Do not grasp mice by the tip of the tail, especially if suspending their entire bodyweight by their tail. This can cause a degloving injury in which the skin of the tail slips off.

- Next, firmly grasp the mouse by the scruff with the same hand that is holding the tail. Grasp with the index finger and thumb near the base of the head and extend the grasp down the mouse’s back by incorporating the middle and ring fingers.

- Be sure to apply just enough pressure, or firmness, to the skin around the neck to prevent the mouse from turning or twisting out of the restraint, but do not pull the skin so tightly that the animal cannot breathe.

- Control of the head is crucial. If the mouse can move its head, it can reach the handler’s fingers and may bite. This may occur when novice handlers grasp the mouse too far down the back, rather than right behind the skull.

- Lift a mouse by the base of the tail and place it on the cage lid, wire bar cage top, or a similar rough surface.

- Mouse restraint two-handed

- Lift a mouse by the base of the tail and place on the cage lid, wire bar lid, or rough surface.

- An alternative method allows the technician to use their lab coat or uniform sleeve covering the forearm to position the animal prior to restraint.

- Pull gently backwards on the tail and the mouse will grasp the surface with four paws and pull forward.

- Next, with the other hand quickly and firmly grasp the mouse by the scruff of the neck (see one handed restraint above).

- With the tail in one hand and the scruff in the other, lift the mouse and tuck the base of the tail between the palm and the 3rd or 4th finger of the hand holding the scruff.

- As with the one-handed method, firmly grasp the scruff to prevent the mouse from twisting or turning while not grasping so firmly that the animal cannot breathe.

- If the mouse is resistant to scruffing, gentle pressure on the mouse’s back can allow the hand to move up for a better grasp.

- Lift a mouse by the base of the tail and place on the cage lid, wire bar lid, or rough surface.

- Rat restraint; scruffing

- Rat scruffing is generally performed two-handed and only in smaller rats. It is not a commonly used technique because rats are less accepting of scruffing than mice, but it is useful in some blood collection situations.

- Grasp the rat by the tail with the non-dominant hand and pull gently backwards on a rough surface (as described above for mice).

- Be careful to grasp near the base of the tail, as the rat’s tail skin can come off if grasped near the tip.

- Hold the tail firmly in the hand and approach the scruff of the rat from the rear.

- For example, if the rat’s tail is in the handlers’ left hand, do not approach the rat from the nose to scruff it with the right hand. Instead, reach over the left hand, and approach the scruff from behind.

- Apply gentle pressure to the back of the rat, over the shoulder blades, then grasp the scruff close to the base of the skull between the fingers and the palm of the hand.

- Control of the head is important to prevent bites. Rat bites can cause serious injury.

- Rats may vocalize when restrained in this fashion.

- Rat restraint; over the shoulder grip

- Grasp the rat by the tail with the dominant hand and pull gently backwards on a rough surface (as described above for mice).

- An alternative method allows the technician to use their lab coat or uniform sleeve covering the forearm to position the animal prior to restraint.

- Be careful to grasp near the base of the tail, as the rat’s tail skin can come off if grasped near the tip.

- Place the non-dominant hand over the rat’s back, approaching from the rear.

- Grasp the rat around the thorax with the ring finger, pinkie, and thumb. The rat’s head should be between the index and middle fingers.

- Do not compress the thorax.

- The rat can be held in this manner with one hand, if the body is stabilized against the handler.

- Grasp the rat by the tail with the dominant hand and pull gently backwards on a rough surface (as described above for mice).

- Rat restraint; under the shoulders grip

- Grasp the rat by the tail with the dominant hand and pull gently backwards on a rough surface (as described above for mice).

- An alternative method allows the technician to use their lab coat or uniform sleeve covering the forearm to position the animal prior to restraint.

- Be careful to grasp near the base of the tail, as the rat’s tail skin can come off if grasped near the tip.

- Place the non-dominant hand over the rat’s back, approaching from the rear.

- Grasp the rat around the thorax, right under the shoulder blades. The rat’s forearms should be gently pushed up with the thumb and index finger.

- The forearms should cross under the rat’s chin, preventing it from biting.

- Do not compress the thorax.

- The rat can be held in this manner with one hand, if the body is stabilized against the handler.

- Grasp the rat by the tail with the dominant hand and pull gently backwards on a rough surface (as described above for mice).

- Decapicone

- A Decapicone is a flexible, cone-shaped piece of thin plastic with a hole in one end. The hole is small enough so the mouse or rat can get its nose out of the hole, but not the rest of the body.

- To restrain the animal, place the mouse or rat in a Decapicone of proper size.

- Push the animal forward until its nose protrudes from the hole in the Decapicone.

- Either hold the bag closed around the tail, or use a twist tie to seal the animal in the cone.

- The advantage of a Decapicone is that the thin plastic allows for injections through the material.

- The disadvantage is that the material does not breathe and animals can become overheated. Only keep an animal in a Decapicone for as long as it takes to perform the procedure.

- Acrylic/rigid plastic restrainer

- Plastic restraint devices are particularly useful when the animal’s tail must be accessed.

- These can be purchased commercially or made in the laboratory.

- The size should be appropriate for the animal to be restrained–the animal should not be able to turn around in the restraint.

- Place the animal in the restraint device by first gently restraining the animal, then releasing it, head-first, at the opening of the device.

- It may help to aim the device upward over the cage, as rodents will often scramble up into a secure structure, like a tube.

- Place the closure on the end of the device, being careful not to damage the animal’s tail, feet, or testicles.

- Minimize time spent in restrainers since animals may overheat.

- Animals may be restrained in other ways as well, such as by wrapping in a small towel, or by simply cupping a hand over the animal. Techniques can be adjusted to meet the needs of the animal and worker. Always take care to avoid bites and scratches and secure the animal from accidental release or falls from heights.

3. Compound Administration Methods

- This is by no means an exhaustive list and other routes are possible. This protocol seeks to illustrate the most commonly used routes. Other routes may require anesthesia of the animal and post-administration pain relief.

- Regardless of administration method used, be sure all materials are prepared before restraining animals.

- Aqueous materials are easier to inject than thicker materials, such as oil-based compounds. Always inject thicker compounds very slowly to avoid dislodging the needle from the syringe.

- General needle and syringe use considerations.

- Always store and dispose of syringes and needles properly.

- If you are new to using syringes and needles, practice handling the syringe and injecting before attempting to inject an animal. Ideally, you will be able to confidently manipulate the syringe and needle with one hand, leaving the other for restraint of the animal. A steady hand minimizes needle movement which minimizes tissue damage.

- Needles have a point, a bevel, a shaft, and a hub. Syringes have a tip, a barrel, and a plunger (Figure 1 a and b).

- Needles are sized by gauge and length. The larger the gauge number, the smaller the needle. Small needles are very prone to dulling (from a burr forming on the tip) and should not be used to pierce multi-dose vials (Figure 1 c). Always choose the shortest needle that will work to administer the compound.

- The needle is attached to the tip of the syringe by the hub. Some syringes have locking tips. Always be sure the syringe is securely attached to the needle.

- Needles are best inserted into the animal with the bevel up, especially for intravenous injections.

- Never recap needles by hand. This is a common cause of needle stick injuries. Dispose of needles and syringes properly in labeled sharps containers. If needles must be recapped, devices are available (Figure 1 d).

- Intranasal (IN)

- Restrain the animal as described above.

- Using a syringe or pipettor, place a small amount of the material to be inhaled at the nares of the animal.

- Watch for the material to disappear into the nares.

- Repeat as necessary until the desired volume has been administered.

- Intramuscular (IM)

- Restrain the animal as described above. Make sure one of the animal’s hind legs is free and stabilized for the injection. Restraint may take two people. If the animal can kick during the injection, muscle damage from the needle will result.

- The needle should be inserted perpendicular to the skin of the animal. Using an appropriately-sized syringe and needle, insert the needle approximately bevel-deep and inject the material into the animal’s quadriceps (the front of the thigh) or lateral thigh muscle mass.

- Do not inject into the posterior muscle mass as it is possible to damage the sciatic nerve.

- If animals are to receive multiple IM injections, alternate legs.

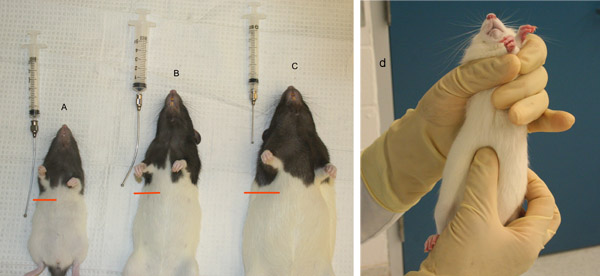

- Intraperitoneal (IP)

- Restrain the animal as described above.

- Tip the animal’s nose toward the floor, exposing the abdomen for injection.

- Locate the animal’s midline and mentally divide the abdomen into quadrants (Figure 2). The lower quadrants, especially the animal’s lower right quadrant, are the appropriate sites for intraperitoneal injections.

- The lower right quadrant is chosen due to the lack of anatomically important structures.

- Using an appropriately-sized syringe and needle, inject the material into the animal.

- If animals are to receive repeated IP injections, alternate the site of injection.

- Subcutaneous (SC, SQ)

- Restrain the animal as described above. The animal must be restrained loosely enough so that the skin may be mobilized.

- If animals are to be handled routinely after SC injection, do not use the scruff (nape of the neck). Instead, use the skin on the dorsal rump or the flank. If animals are to receive multiple SC injections, alternate sites of injection.

- Grasp the skin and gently pull it upwards, making a “tent”.

- If performing the injection solo, insert the needle and gently tent the skin upwards with the needle to confirm that the needle is in the subcutaneous space.

- Using an appropriately-sized syringe and needle, insert the needle at a 30-45° angle into the tented skin, and inject the material. Inject parallel to and away from the fingers holding the skin upwards.

- If the injection is successful, a small swelling under the skin will be seen.

- After injection, apply gentle pressure to prevent backflow of the material.

- Intradermal (ID)

- For intradermal injections, animals are often shaved so that the skin may be seen.

- Restraint of the animal for multiple intradermal injections may be difficult. In that case, chemical sedation may be necessary. The sites for ID injections are the same as those for SC.

- Insert an appropriately-sized needle into the skin at a 15-30° angle. The needle will not be inserted very far and the injection should meet with resistance.

- An alternative approach is to gently pinch the skin adjacent to the injection site and insert the needle at a very shallow angle. This is useful in mice since it prevents them from moving during the injection process.

- If the injection is successful, a small bleb will be seen. It will be paler than the surrounding skin.

- After injection, apply gentle pressure to prevent backflow of the material.

- Intravascular (IV)

- The left and right lateral tail veins are the most common vascular access route used in mice and rats.

- Other vascular access routes are possible in mice and rats, but generally require sedation and post-injection pain relief.

- For a tail vein injection, restrain the animal in a Decapicone or plastic rodent restrainer.

- Place the animal’s tail under a lamp, or on a protected warming device. This will promote vasodilation, allowing for easier injection.

- Do not overheat the animal.

- For large male rats, cleaning the skin scales off the tail may allow for better visualization of the vein. Cleaning should be gentle so the skin is not abraded.

- Hold the animal’s tail by the tip with the non-dominant hand. This will straighten the tail.

- Rotate the tail ¼ turn to place the tail veins dorsally for easier injection. The animal has two lateral tail veins and a ventral tail artery (Figure 3).

- Approach the tail with the needle at a 15-20° angle. Start at the distal portion of the tail.

- The veins are shallow and the needle should not be inserted much beyond the bevel.

- If the injection is begun as distally as possible, there is more undamaged vein to attempt the injection, should the first try fail.

- Inject the material. A successful injection will result in the material entering the vein with no resistance and blanching of the tail vein for the duration of the injection.

- Do not aspirate before injecting, as this will collapse the vein.

- Gentle pressure on the venipuncture site after injection will prevent bleeding.

- In an unsuccessful injection, the material will not flow easily. Instead, the tail skin will blanch or the material cannot be injected at all.

- Intragastric administration (oral gavage)

- Only perform gavage on restrained, awake animals. Anesthesia or sedation increases the risk of aspiration (material inadvertently entering the lungs).

- Select an appropriately sized oral feeding needle for use. These needles have ball tips at the end to prevent their passage into the trachea.

- Length needed can be determined by holding the restrained animal up and measuring from the corner of the mouth. The ball tip of the feeding needle should reach to the animal’s last rib (Figure 4). Needle gauge is determined by the weight of the animal.

- Restrain the animal so that its head and body are in a straight, vertical line. This straightens the esophagus, allowing for easier passage of the feeding needle.

- Insert the ball tip of the needle into the animal’s mouth, over the tongue. Once the needle is in place, bring the needle and syringe up, pressing gently against the palate, so the animal’s nose is toward the ceiling.

- In rats the needle may need to be redirected slightly as it passes the back of the throat. Any tension on the needle indicates the need to adjust position

- Continue to pass the needle until the predetermined distance is reached. The needle should pass easily, and the animal should not gasp or choke.

- Administer the substance. It should flow into the stomach. If there is resistance or the animal gasps, chokes, or turns blue, immediately stop and remove the needle. Animals that have aspirated may require euthanasia, depending on the compound being administered.

4. Representative Results

When animals are handled correctly, there is a minimum of stress for both animal and handler. Handlers do not get bitten or scratched, and animals are handled humanely and competently. Compounds are administered via the correct route with minimal damage to tissue and as little discomfort to the animal as possible.

If investigators are new to handling animals, working with a small stuffed animal may be helpful. There are also animal simulators available for some techniques, such as the Koken rat. For many investigators, there is little chance to gain familiarity with needles and syringes before working with animals. Representative parts of a needle and syringe are illustrated in Figure 1A and 1B. Before injecting animals for the first time, it can be useful to practice injecting before working with animals. Very fine needles, such as 28 and 30 g, are easy to damage. If withdrawing substances from multi-use vials, use a larger needle for that purpose and then replace it with the smaller gauge needle for injection. A burred needle is seen in Figure 1C. Basic safety precautions should be taken when working with needles, such as not recapping used needles by hand. Figure 1D shows a needle recapper in use. This can be valuable to investigators who need to remove needles to, for example, express blood from a syringe without the hemolysis seen when blood is pushed through a needle.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate landmarks for intraabdominal injection and the typical structure of the tail, illustrating the targets for injection. Figure 4 provides examples of proper sizing of gavage needles. Gavage needles should reach from the mouth of the animal to right below the last rib.

Figure 1. A) Needle and B) syringe parts, labeled. C) Burr on needle caused by repeated placement of the needle into a multi-use vial. D) Needle recapper in use.

Figure 2. Quadrants of the ventral abdomen. Only inject into the lower two quadrants, preferentially the right lower quadrant.

Figure 3. Schematic of the tail in cross-section, illustrating the relationship of the arteries and veins to the bony and tendenous structures.

Figure 4. Gavage needle sizing in rats. A) Gavage needle too long. B) Appropriately sized gavage needle. C) Gavage needle measurement too short, D) Palpating for the last rib to determine appropriate gavage needle size.

| Mouse | Rat | |||

| Route | Recommended volume | Recommended gauge and length of needle | Recommended volume | Recommended gauge and length of needle |

| Intranasal1 | 5-25 μl | N/A | 5-25 μl | N/A |

| Intramuscular1,2 | 0.00005 ml/g | <23 g, 0.5 to 0.75 in | 0.1 ml/kg | <21 g, 0.5 to 0.75 in |

| Intraperitoneal1,2 | 0.02 ml/g | <21 g, 0.75 to 1 in | 10 ml/kg | <21 g, 0.75 to 1 in |

| Subcutaneous1,2 | 0.01 ml/g | <22 g, 0.5 to 1 in | 5 ml/kg | <22 g, 0.5 to 1 in |

| Intradermal1 | 0.05-0.1 ml | <26 g, 0.5 in | 0.05-0.1 ml | <26 g, 0.5 in |

| Intravenous1,2 | 0.005 ml/g -0.025 ml/g* | <25 g, 0.75 to 1 in | 5 ml/kg-20 ml/kg* | <23 g, 0.75 to 1 in |

| Oral gavage1,2 | 0.01 ml/g | 20-22 g feeding needle | 5-10 ml/kg | 16-20 g feeding needle |

*The first number is the volume given as an intravenous bolus over approximately 1 minute. The second volume is the volume that may be given as a slow infusion over 5-10 minutes.

Table 1. Recommended doses and needle sizes for various routes of compound administration in mice and rats.

Discussion

This protocol should be viewed as an introduction to animal handling and substance administration meant to supplement hands-on training provided at the researcher’s facility. The means of restraint that will be used and the routes of substance administration should be considered in the experimental design and when the research protocol or ethics committee protocol is written.

Training in animal-related procedures is vital to the success of research. To perform most experiments, animals must be handled by research staff, and the better the animal handling, the less stressed the animal 3. Accustoming animals to gentle human contact can reduce stress and make animals more tractable research subjects 4,5. Handling stress has been shown to affect some types of research 6 and it is possible it can affect others as well. Restraint of rodents should be accomplished with careful, but firm handling (a tentative grip is likely to result in injury to rodent and handler) and should be for the shortest duration practical. Restraint methods are usually chosen based on the size of the animal or the access sought. For example, handling adult rats by the scruff, although possible, is often met with strong resistance by the rat, especially if the handler is inexperienced. Holding a mouse or rat by hand can make access to the tail veins difficult and a restraint device is often chosen to keep the animal as still as possible.

When researchers handle animals, they are often seeking to administer a compound or biologic for further study. The route of administration of substances can affect absorption, bioavailability, and suitability for a particular experiment. Familiarity with various routes should provide researchers with the ability to administer their substance in the best way possible for their research. For example, a route that promotes rapid absorption of a substance, such as intravenous or intraperitoneal, should not be used if the researcher wants to administer the substance in a slower-acting manner. Recent reviews of some of these techniques and considerations for volume, equipment, and solute may be found in two papers by Turner et al. 1,7

Whenever substances are to be administered to laboratory rodents, consideration should be given to the proper size of equipment and volume of substance (outlined in Table 1). Improperly sized equipment or large volumes may result in discomfort, injury, or death of the animal. Generally, substances administered parenterally are sterile, except where the research goals would make this impossible (i.e., bacterial studies). Compounds and biologicals should be in a solute or vehicle that will have the least effect on the animal. A physiologic pH (7.3 -7.4) is generally well-accepted, especially for subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intraperitoneal routes. Non-physiologic pH levels in substances administered by these routes may result in pain or necrosis and tissue damage. Wider ranges of pH are tolerated with intragastric and intravenous routes 7. In small rodents, another important consideration is the possibility of chilling if large volumes of room-temperature fluids are given. If fluids are being administered intravenously or intraperitoneally, especially in support of an ill animal, they should be warmed to body temperature (37 °C).

The routes of administration discussed in this protocol are ones commonly used in many research programs, are simple to master, and generally do not require anesthesia. An almost infinite variety of routes of administration are possible, however, including intracranial, intrathecal, epidural, intratracheal, intraosseous, and intraarticular to name but a few. Training in these specialized routes of administration should be sought from people who have extensive experience with the route and good outcomes.

In rodents, the intranasal route is typically used to study substances introduced to the lungs via a more “natural”; method than intratracheal instillation. Mice and rats are obligate nose-breathers, so inducing them to inhale very small amounts of fluid is not difficult, even in conscious animals. Since the nasal mucosa is well-supplied with blood vessels, intranasal administration of some substances can be similar to intravenous administration. This route is not recommended in animals with rhinitis, however, as that may compromise absorption. Attempts to administer large volumes by the intranasal route may result in dyspnea or drowning of the animal.

Intramuscular injections provide rapid absorption of substances. Intramuscular injections can be challenging in rats and mice due to their small size and correspondingly small muscles. They are performed in the hind legs. Due to the potential for damage of the sciatic nerve, the quadriceps femoris is the muscle of choice.

Although both the subcutaneous and intradermal routes involve the skin, there are differences between the bioavailability of substances placed in the skin vs the subcutis. Subcutaneous administration is often considered a “deposition” route, with slower absorption than other routes, such as intravenous or intraperitoneal. Intradermal administration is used for very small volumes of substances, typically immunostimulatory substances such as adjuvant-antigen mixtures. In both cases, the substances administered should be of physiologic pH and non-irritating. Intradermal or subcutaneous injections should not be performed in the scruff, since this is a commonly used site for restraining the rodent.

Intravenous and intraperitoneal administration are often considered equivalent in rodents. Intravenous routes of dosing provide more rapid uptake of compounds, however, while intraperitoneal administration should be considered roughly equivalent to oral administration 8. Care should be taken with compounds administered intraperitoneally as they may cause pain if improperly buffered. The common route of intravenous bolus administration in rodents is via the tail veins. If chronic intravenous administration of a substance is desired, implantation of venous or arterial cannulae should be considered. Substances administered intravenously should be delivered aseptically and should be shown to be safe to administer intravenously. For example, substances that may induce hemolysis ,thrombosis, or vasculitis are not appropriate for intravenous administration.

The intragastric or oral gavage route is often used to mimic a common dosing route in humans. It also allows for precise dosing of substances when compared to oral administration through food or water. Bioavailability of compounds administered via gavage will vary based on the fed/fasted state of the animal, as well as the solute or vehicle of the compound or biological. Gavage or feeding needles should be of the appropriate size for the animal being used, and should be cleaned between animals, if disposable gavage needles are not practical. Injuries caused by gavage are not uncommon and include deposition of the substance into the lung or rupture of the stomach or esophagus. Training should be supervised by an experienced party and undertaken on euthanized animals first, then anesthetized animals (that will be euthanized) before gavage on awake animals is attempted. First gavage attempts on awake animals should involve average-sized animals and small volumes of a substance, such as saline, that will not cause injury if the procedure goes awry. Animals should be closely assessed for signs of distress, such as gasping, turning blue, bleeding, or excess salivation ,after gavage and euthanized if necessary. If euthanasia is required, the animal should be necropsied to determine why the gavage procedure failed.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The research presented here was supported by Charles River.

Materials

| Name of the reagent | Company | Catalogue number | Comments |

| Needles | Various | Various | Needles are sold by both gauge and length. Check both before ordering. |

| Syringes | Various | Various | Always choose an appropriate size for the volume to be administered. |

| DecapiCones | Braintree Scientific | DC-200, DCL-120, MDC-200 | Available in mouse and rat sizes. |

| Rodent restrainer | Harvard Apparatus, Braintree Scientific, Plas-Labs, others | Available in clear Plexiglas, adjustable plastic, and sized for mice and rats. | |

| 50 ml conical tube | Various | ||

| Feeding needles | VWR, Popper and Sons | Various | Fit the needle gauge and length to the animals as described above. Both disposable and reusable feeding needles are available. |

References

- Turner, P. V., Brabb, T., Pekow, C., Vasbinder, M. A. Administration of substances to laboratory animals: routes of administration and factors to consider. JAALAS. 50, 600-613 (2011).

- Diehl, K. H. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 21, 15-23 (2001).

- Hurst, J. L., West, R. S. Taming anxiety in laboratory mice. Nat. Methods. 7, 825-826 (2010).

- Maurer, B. M., Döring, D., Scheipl, F., Küchenhoff, H., Erhard, M. H. Effects of a gentling programme on the behaviour of laboratory rats towards humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 111, 329-341 (2008).

- Cloutier, S., Newberry, R. C. Use of a conditioning technique to reduce stress associated with repeated intra-peritoneal injections in laboratory rats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 112, 158-173 (2008).

- Romanovsky, A. A., Kulchitsky, V. A., Simons, C. T., Sugimoto, N. Methodology of fever research: why are polyphasic fevers often thought to be biphasic. Am. J. Physiol. 275, 332-338 (1998).

- Turner, P. V., Pekow, C., Vasbinder, M. A., Brabb, T. Administration of substances to laboratory animals: equipment considerations, vehicle selection, and solute preparation. JAALAS. 50, 614-627 (2011).

- Lukas, G., Brindle, S. D., Greengard, P. The route of absorption of intraperitoneally administered compounds. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 178, 562-564 (1971).

- AALAS. . Laboratory Mouse Handbook. , (2009).

- AALAS. . LAT Training Manual. , (2009).

- AALAS. . LATg Training Manual. , (2009).

- Barnett, S. W. . Manual of Animal Technology. , 440 (2007).

- Baumans, V., Pekow, C. A., Hau, J., Schapiro, S. J. . Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science. 1, 401-446 (2010).

- Bogdanske, J. J., Hubbard-Van Stelle, S., Riley, M. R., Schiffman, B. M. . Laboratory Mouse Procedural Techniques. , (2011).

- Danneman, P., Suckow, M. A., Brayton, C. . The Laboratory Mouse. , (2000).

- Sharp, P. E., La Regina, M. C. . The Laboratory Rat. , (1998).