A Murine Model of Stent Implantation in the Carotid Artery for the Study of Restenosis

Summary

A model of stent implantation in mouse carotid artery is described. Compared to other similar methods, this procedure is very rapid, simple and accessible, offering the possibility to study in a convenient way the vascular wall reaction to different drug-eluting stents and the molecular mechanisms of restenosis.

Abstract

Despite the considerable progress made in the stent development in the last decades, cardiovascular diseases remain the main cause of death in western countries. Beside the benefits offered by the development of different drug-eluting stents, the coronary revascularization bears also the life-threatening risks of in-stent thrombosis and restenosis. Research on new therapeutic strategies is impaired by the lack of appropriate methods to study stent implantation and restenosis processes. Here, we describe a rapid and accessible procedure of stent implantation in mouse carotid artery, which offers the possibility to study in a convenient way the molecular mechanisms of vessel remodeling and the effects of different drug coatings.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases caused by the progression of atherosclerosis are the leading cause of death in the industrialized nations. Atherosclerosis is a focal, inflammatory fibro-proliferative response of the vascular wall to endothelial injury1, resulting in the formation of an extended plaque into the lumen of the vessel, affecting the blood flow through coronary arteries. Over 75% of myocardial infarctions result from the rupture of the thin fibrous cap of the inflamed plaque2. Since this complication can be fatal, a percutaneous transluminal (coronary) angioplasty (PTCA) with stent implantation became the first-choice therapy in the current medical practice. The method allows the dilatation of the narrowed coronary artery and thus the restoration of blood flow. Simultaneously, it causes an extent injury to the endothelium and vessel wall3. However, the long-term effect of this therapy is limited by an excessive arterial remodeling and restenosis4.

By employment of stents, the PTCA became more effective in the treatment of complicated lesions, allowing revascularization after an acute vessel closure5. This method decreases the incidence of in-stent restenosis to less than 10%6. Beside these benefits, this first-choice therapy for coronary revascularization bears also the life-threatening risks of in-stent thrombosis and restenosis.

In-stent thrombosis is caused by a de-endothelialization of the vessel, followed by a massive adhesion of platelets and fibrin to the injured site. 26% of patients suffer from in-stent thrombosis and 63% die of myocardial infarction7. Restenosis refers to the process of wound healing after mechanical injury to the vessel wall, involving neointimal hyperplasia (migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), and remodeling of the vessel. Often, an invasive re-intervention becomes necessary to dilatate severely narrowed atherosclerotic vessels due to in-stent thrombosis and restenosis.

To prevent in-stent thrombosis, a long-term treatment with anti-thrombotic drugs is necessary8. To prevent restenosis, new generation of drug-eluting stents elute anti-proliferative agents such as immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. sirolimus, everolimus, zotarolimus) and anti-cancer drugs (e.g. paclitaxel) from a polymer coating for several months9,10. Although these drugs decrease the neointima formation and restenosis, they maintain a high risk of in-stent thrombosis by inhibiting the re-endothelialization.

After arterial injury, the maintenance of the endothelial compartment is essential to prevent thrombotic complications. Under physiological conditions, the human endothelium shows a small turnover rate11. Under pathological conditions, however, the endothelial integrity is impaired, so that a rapid recovery by surrounding mature endothelial cells and circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) is required12,13.

The study of these complex molecular mechanisms in larger animals14-16 or in mouse aortic artery is a very difficult procedure, offering limited data17-19. To test the efficiency of novel stent-coatings to reduce in-stent thrombosis and restenosis new models are imperative.

Nitinol represents the ideal platform for stents because of its’ high elasticity, shape-memory effect and good tolerance in patients, being successfully used as bare-metal stents in clinical use. This alloy made it possible to create a miniaturized stent with an external diameter of 500 μm, which can be coated20 and implanted into the carotid artery of mice. The development of a miniaturized nitinol stent for mouse carotid artery, allows the study of precise molecular mechanisms induced by stent implantation and offers the possibility to test quickly and efficiently the effects of different drug-coatings to prevent restenosis. Moreover, the existence of different knock-out mice strains represents a huge advantage in clarifying the role of different molecules involved in neointima growth and in-stent thrombosis.

Protocol

1. Stent Preparing and Implantation

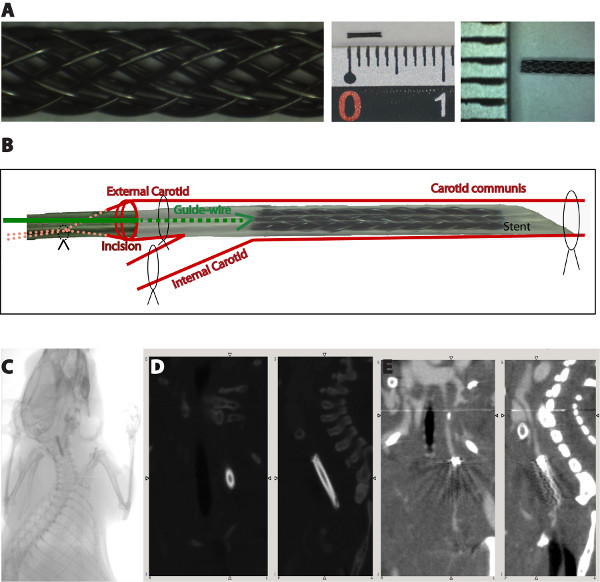

- The stent-struts (Fort Wayne Metals, Castlebar, Ireland) were braided and then cut to the desired size at the Institute for Textile Technology and Mechanical Engineering, RWTH Aachen University in Germany (Figure 1A).

- Before implantation, the stents must be transferred into a 2 cm silicon tube, using forceps, and placed 2 mm at one terminal end, referred front end (Figure 1A).

- The front end should be cut obliquely, to ensure a sharp tip for implantation.

- Before implantation, the stent should be abundantly watered, to ensure slippage.

2. Stent Implantation

- 10-12 weeks old male C57Bl/6 wild type mice, 25-27 g are anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. Proper anesthetization is confirmed prior to surgery by the lack of reflexes and beard movement. To prevent dryness while under anesthesia, the mouse eyes are covered by a film of bepanthene cream.

- After shaving and proper disinfection of the ventral neck area, a small median incision of 1 cm is performed under a stereomicroscope, using scissors. After separating the 2 fatty bodies with sterile curved forceps, the left common carotid artery can be seen pulsing along with the trachea.

- 1 cm of the left common carotid artery and the bifurcation should be free prepared. 1 knot using a 5/0 silk thread will be bound around the left common carotid artery, 2 knots using 7/0 silk threads will be bound around the left external carotid artery, and 1 knot using a 7/0 silk thread will be bound around the internal carotid artery (Figure 1B).

- The blood flow is then interrupted by binding the knots on the internal carotid artery and the proximal external carotid artery firmly, as well as by pulling the knot surrounding the common carotid artery. The vessel should be fixed in a way that the common and external carotid artery are in a straight line.

- A small incision at the external carotid artery is performed, near the proximal knot, using a Vannas scissor. The silicon tube containing the stent is introduced into the external carotid artery, with the sharp end in front, using a guide-wire. After the stent reaches the desired position, the silicon tube is pulled back over the guide-wire and allows the shape-memory expansion of the stent (Figure 1B).

- The distal knot on the external carotid artery is bind tightly to close the site of incision and the knots at the internal and common carotid artery are removed, thereby restoring the blood flow.

- The skin incision is closed using 3-4 Michel suture clips and a Michel forcep. The mouse is placed under the red light until full recovery. An analgesic treatment is not necessary.

- The plaque can be analyzed after 1-3 weeks. To study the re-endothelialization, an earlier end-time point is necessary (3-4 days). We observed in our model of stent implantation that 4 weeks after this surgical intervention, especially by the use of specific coatings to biofunctionalize the miniaturized stents, neoangiogenesis occurs in approximately 30% of specimen. This is a hind for remodeling and regenerative processes, with different mechanisms and representing another pathological problem. To concentrate on neointima formation, in-stent stenosis and/or analysis of mechanisms underlying these side-effects after stent implantation an end-time point of 3 weeks would be beneficial not to mix up with the regenerative effects induced by the onset of neoangiogenesis.

3. Analysis of Plaque Formation

- At the end-time point, the animals are anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. Proper anesthetization is confirmed prior to surgery by the lack of reflexes and beard movement.

- The animals are killed by intracardial exsanguination. The serum blood is collected for further analysis.

- After opening the thoracic cavity and PBS washing via intracardial punction, a body-perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution is performed for 5 min. The left carotid artery containing the stent is dissected, directly placed in a 4% PFA solution and at least 16 hr later embbeded in plastic.

- 50 μm thick sections are performed from plastic-embedded samples using a diamond band saw.

- To measure the plaque size, Giemsa staining is performed.

- To analyze the rate of re-endothelialization within the stented area of the vessel, immunohistochemistry for von Willebrand factor (vWF) is performed.

Representative Results

- The implantation of a miniaturized nitinol stent into the left carotid artery of mice takes 25-30 min and shows a mortality rate of 10% mostly due to the damage of the vessel during the intervention. A better survival rate is observed in mice having a weight more than 25 g at the time of stent implantation (mortality rate of 5%). Therefore, we chose for the implantation mice with a weight between 25-27 g. After surgery, the mice recover from anesthesia within 2-5 min and no physical impairments, like e.g. paralysis, are observed. Micro-Computer Tomography (Micro-CT) imaging performed one week after stent implantation showed that the stents are not dislocated by blood flow (Figure 1C). Unfortunately, analysis of neointima formation in these images is not possible due to the metal-derived artifacts (Figure 1D, 1E).

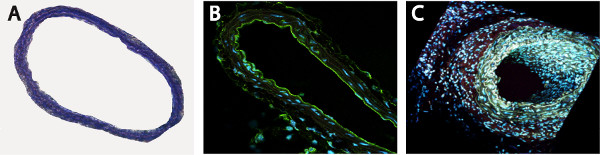

- We didn’t observe any vessel or endothelial damages of unstented area of the vessel, immediately below the stent, as detectable by histological (Figure 2A) and by specific staining for endothelium (Figure 2B, anti-mouse CD31 antibody). For a better overview, the section was scanned using a two-photon laser scanning microscopy (Figure 2B, 2C).

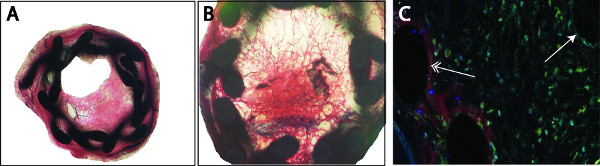

- In the stented vessel, a permanent dilatation of 15% is detected (ratio stent:artery, 1,15:1) by mice with a weight between 25-27 g. Neointima formation and thrombus-formation can be analyzed by classical histological stainings (e.g. Hematoxilin-eosin, Giemsa, Movat, Toluidin Blue, Masson-Trichrom-Goldner, Figure 3A, 3B). Since the lamina externa and interna are not visible anymore, plaque size was calculated as the difference of the external and the luminal areas (mean plaque area: 234566 ± 3315 μm2, mean luminal area: 12036 ± 2662 μm2). External circumference was also measured (mean: 1799 ± 14 μm). For analysis of the cellular composition, the sections need to be deplastified and stained with specific markers. For the re-endothelialization, we used a Cy3-conjugated anti-CD31 antibody and for smooth muscle cell proliferation a FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (Figure 3C). Re-endothelialization was calculated as percentage of CD-31 positive stained to the total luminal surface (mean: 23.07 ± 3.14 %) one week after stent implantation.

Of course, an unlimited number of specific staining is possible, depending on each laboratories’ experience. Analysis of myosin heavy chain, for a better characterization of SMCs, but also analysis of infiltrated cells (monocytes, lymphocytes), or stainings for different inflammatory cytokines can also be performed, depending on the aim of the study.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the surgical procedure (A). The blood flow is interrupted by binding the knots on the internal carotid artery and the proximal external carotid artery firmly, as well as by pulling the knot surrounding the common carotid artery. The silicon tube containing the stent is introduced into the external carotid artery through a small incision at the external carotid artery. After the stent reaches the desired position, the silicon tube is pulled back over the guide-wire and allows the shape-memory expansion of the stent. Micro-CT images showing the stent position one week after surgical implantation (B). Due to the material-derived artifacts, an analysis of the neointima growth is not possible (C,D).

Figure 2. Unstented area of the vessel is not affected by the surgical procedure, as shown by Toluidin Blue (A) and endothelial-specific CD31 staining (B, C).

Figure 3. Analysis of the plaque can be performed by classical histological stainings (e.g. Masson-Trichrom-Goldner) (A). The organized thrombus can be detected by black-stained fibrin depositions inside the neointima, in some cases a complete occlusion of the vessel is observed (B). Re-endothelialization (Cy3, red) or smooth muscle cell proliferation (FITC, green) was detected by double immunofluorescence staining using specific markers. Counterstaining was performed with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) (C). We noticed a completed re-endothelialization of the stent struts (left, double arrow) compared to an incompleted luminal re-endothelialization (right, single arrow).

Discussion

To reduce the risk of in-stent thrombosis and restenosis and to sustain the development of new coatings for drug-eluting stents, an easy, simple and accessible method of stent implantation in an animal model is needed. Mice deliver the ideal system to study the complex mechanisms of arterial remodeling after stent implantation and the efficiency of such drugs. Existing models for in-stent restenosis in mouse are difficult, require high surgical skills and imply high risks of complications as bleeding or paralysis17-19. For example, in the model of the stent- implantation into thoracic aorta of a donor mouse after balloon-dilatation of the vessel and then transplantation of the stented segment into carotid artery of a recipient mouse17, the study of the patho-mechanisms is not influenced only by recipient reaction to donor material, but also by the massive damaging of vasa vasorum and adventitia. Implantation of a stainless steel stent directly into abdominal aorta after balloon-dilatation19 is followed by a high mortality rate (35%) because of hind leg paralysis after thrombosis or bleeding from abdominal aorta on site of arteriotomy. Implantation of a spiral-shaped self-expanding nitinol-stent into abdominal aorta via femoral artery18 needs high surgical skills, mostly due to blindly directing the stent along the branching from femoral artery to aorta to place the stent at the right position. This procedure is followed by a high risk of damaging the femoral nerve, therefore paralysis of the hind leg. Compared with these procedures, our model of stent implantation in mouse does not need high surgical skills.

Our model offers a simple, easy and efficient method to analyze the effects of different drug-coatings on arterial remodeling, the placing of the stent is made under sight, and there are no risks of damaging nerves or other structures. The complex molecular mechanisms can be investigated easier in our model of mouse carotid artery stenting, not only by direct accessibility of the vessel, but also due to the existence of different knock-out mice strains.

As one limitation, comparing with the clinical procedure, our model uses healthy mice/arteries and doesn’t perform stenting on pre-existing plaques (not in-stent restenosis, but in-stent stenosis). We also don’t perform balloon-dilatation prior to stent-implantation. However, due to the massive damage of the vessel wall in both models, the reparatory processes are similar. Unfortunately, due to the metal-derived artifacts, an in vivo monitoring of the neointimal growth is not possible by existing imaging methods as ultrasound or computer-tomography. Another limiting factor is the thin sectioning of metal-based stents, which requires some expertise in the metal processing.

Using this method, we were able to show, that neutrophil-instructing biofunctionalized miniaturized nitinol-stents coated with LL-37 reduce in-stent restenosis, providing a novel concept to promote vascular healing after interventional therapy21.

Despite these limitations, this model seems to be, until now, the most suitable system, thereby money- and time-saving, to investigate new drug-coatings for stents and their effects on the molecular events during arterial remodeling. Moreover, this model can be easily adapted to the hamster, which is more similar to the human, so that every therapeutical hypothesis can be verified before applying to larger animals or human to avoid unpleasant and unexpected effects.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Angela Freund for the excellent technical assistance in sectioning the plastic embedded stents. We thank also Mrs. Roya Soltan and Mrs. Angela Freund for the professional help with immunohistochemistry staining.

Materials

| Name of the reagent | Company | Catalogue number | Comments (optional) |

| nitinol-stents (self-made from nitinol-struts) | Fort Wayne Metals, Castlebar, Ireland NiTi#1, superelastic, straight annealed, light oxide, diameter 500 μm | custom-made product | Institute for Textile Technology and Mechanical Engineering |

| silicon tube | IFK Isofluor, Germany | custom-made product | diameter 500 μm, section thickness 100 μm, polytetrafluorethylene catheter |

| stereomicroscope | Olympus | SZ/X9 | |

| forceps | FST, Germany | 91197-00 | standard tip curved 0.17 mm |

| Ketamine 10% | CEVA, Germany | ||

| Xylazine 2% | Medistar, Germany | ||

| Bepanthene | Bayer, Germany | ||

| Scissors | FST, Germany | 91460-11 | Straight |

| Vannas scissor | Aesculap, Germany | OC 498 R | |

| 5/0 Silk | Seraflex | IC 108000 | |

| 7/0 Silk | Seraflex | IC 1005171Z | |

| guide-wire | Abbott Vascular | 1001782-HC | 0.014-inch angioplastie guide-wire |

| Michel suture clips | Aesculap, Germany | BN507R | 7.5 x 1.75 mm |

| Michel Forcep | Aesculap, Germany | BN730R |

References

- Ross, R., et al. Response to injury and atherogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 86, 675-684 (1977).

- Virmani, R., et al. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 13-18 (2006).

- Farb, A., et al. Pathology of acute and chronic coronary stenting in humans. Circulation. 99, 44-52 (1999).

- Weber, C., Noels, H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat. Med. 17, 1410-1422 (2011).

- Lenzen, M. J., et al. Management and outcome of patients with established coronary artery disease: the Euro Heart Survey on coronary revascularization. Eur. Heart J. 26, 1169-1179 (2005).

- Babapulle, M. N., et al. A hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. Lancet. 364, 583-591 (2004).

- Wiviott, S. D., et al. Intensive oral antiplatelet therapy for reduction of ischaemic events including stent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: a subanalysis of a randomised trial. Lancet. 371, 1353-1363 (2008).

- van Werkum, J. W., et al. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: the Dutch Stent Thrombosis Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 1399-1409 (2009).

- Finn, A. V., et al. Vascular responses to drug eluting stents: importance of delayed healing. Arterioscler. Thromb Vasc. Biol. 27, 1500-1510 (2007).

- Joner, M., et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 193-202 (2006).

- Cines, D. B., et al. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 91, 3527-3561 (1998).

- Hristov, M., Weber, C. Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization, pathophysiology, and possible clinical relevance. J. Cell Mol. Med. 8, 498-508 (2004).

- Rabelink, T. J., et al. Endothelial progenitor cells: more than an inflammatory response?. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 834-838 (2004).

- Schwartz, R. S., et al. Preclinical evaluation of drug-eluting stents for peripheral applications: recommendations from an expert consensus group. Circulation. 110, 2498-2505 (2004).

- Schwartz, R. S., et al. Differential neointimal response to coronary artery injury in pigs and dogs. Implications for restenosis models. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14, 395-400 (1994).

- Schwartz, R. S., et al. Restenosis and the proportional neointimal response to coronary artery injury: results in a porcine model. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 19, 267-274 (1992).

- Ali, Z. A., et al. Increased in-stent stenosis in ApoE knockout mice: insights from a novel mouse model of balloon angioplasty and stenting. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 833-840 (2007).

- Chamberlain, J., et al. A novel mouse model of in situ stenting. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 38-44 (2010).

- Rodriguez-Menocal, L., et al. A novel mouse model of in-stent restenosis. Atherosclerosis. 209, 359-366 (2010).

- Costa, F., et al. Covalent immobilization of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) onto biomaterial surfaces. Acta Biomaterialia. 7, 1431-1440 (2011).

- Soehnlein, O., et al. Neutrophil-derived cathelicidin protects from neointimal hyperplasia. Science Translational Medicine. 3, 103ra198 (2011).