Task Interruption and Resumption Paradigm for Testing the Activation and Pursuit of an Abstract Thinking Goal

Summary

This protocol was designed to test the activation and pursuit of cognitive goals (e.g., an abstract thinking goal) using the task interruption and resumption paradigm. The protocol is suitable for cognitive goals that are automatically pursued once activated, as the distraction procedure prevents goal pursuit during the interruption period.

Abstract

This protocol is based on the task interruption and resumption paradigm, the premise of which is that active goals lead to persistent behavior and thus a higher resumption rate after a period of delay or interruption. The task interruption and resumption protocol described in this research is tailored to test the activation of cognitive goals (e.g., a goal to think more abstractly). Cognitive goals may be pursued even during the interruption period; thus, to prevent this, the protocol involves cognitive distraction. The protocol consists of several stages. Specifically, the initial stage includes the goal activation process, where the treatment (versus control) condition receives a manipulation to activate the cognitive goal being tested by the researcher. In the next stage, participants are presented with the introduction of a task that is perceived to either satisfy or not satisfy the cognitive goal of interest. Importantly, this task is interrupted a few seconds after it begins. The task interruption forces a delay period and introduces a cognitive distraction to prevent the automatic pursuit and fulfillment of the cognitive goal. After the interruption period, participants are given a choice between resuming the interrupted task and abandoning the interrupted task to complete an alternative task instead. Among participants whose cognitive goals had been activated at the earlier stage, the task resumption rate should be higher if the task was perceived as an opportunity to satisfy (versus not satisfy) the goal. Such a finding would provide empirical evidence that the cognitive goal has been activated and pursued. In previous research, this protocol has been used to test whether causal uncertainty activates an abstract thinking goal. Adapting the protocol to test the activation of other cognitive goals is also discussed.

Introduction

Goal pursuit can take many forms, from educational attainment to healthy diets to finding happiness. Much research on goal pursuit investigates factors that moderate motivation levels or goal commitment1,2,3,4,5, while others focus on examining the consequences of active goals6,7,8,9,10. The methodology described and discussed in the current paper was specifically developed to test the activation and pursuit of cognitive goals and the associated consequences. A cognitive goal (or thinking goal) is defined as a desired state of mind11. Cognitive goals may encompass specific thought outcomes, such as those related to motivated reasoning12 or confirmation bias13, or they may be about achieving a certain mode of thinking, whether it is to be more accurate14 or to think more creatively15 or at a higher level11. While the antecedents and consequences of various cognitive goals have been examined in various empirical settings, the activation of these motivational states has often been implied rather than directly tested. For example, several studies have indirectly manipulated the need for cognitive closure by manipulating time pressure, but the actual activation of the motivational state was implied based on prior research16,17,18,19.

The setup of this methodology is based on one of the principles of goal pursuit6,10,20: that unsatisfied active goals lead to persistence, so individuals have a high tendency to resume if they have been interrupted during goal pursuit. In contrast, if the interrupted task is unrelated to goal pursuit, the rate of resumption amongst individuals would be relatively lower. To illustrate, an individual shooting hoops to reach a certain success rate is highly likely to resume the activity after being interrupted by a lunch break, even if there are other available activities that could be more appealing (e.g., playing a video game or taking a nap). In contrast, if the individual is shooting hoops simply because it is a convenient activity at the time, there is a lower chance that this person would resume after taking a lunch break, especially if other appealing activities are available.

A cognitive goal, when activated, would also result in a higher resumption rate if the individuals are interrupted during goal pursuit. However, there is a critical difference between interrupting a behavioral goal pursuit and interrupting a cognitive goal pursuit. Interrupting a behavioral goal pursuit typically means that the interruption is successful in pausing the goal pursuit process because, for instance, just as it is difficult to shoot hoops and eat lunch at the same time, it is challenging for people to be physically engaged in two separate tasks simultaneously. This is not the case, however, when interrupting the pursuit of cognitive goals. People can continue to have and develop thoughts, even during periods of interruptions, which is why people often find themselves persistently pondering unresolved issues, even when forced to step away to eat a meal or take a shower. In fact, recent studies have demonstrated that people engage in complex cognitive processes even when asleep21,22,23. The protocol introduced in the current research is designed to address this unique characteristic of cognitive goal pursuit: that people can continue to pursue and potentially even satisfy the activated cognitive goal during the interruption period. Specifically, this protocol includes an activity that distracts participants during the interruption stage to prevent automatic goal pursuit.

The gist of this protocol involves: (1) manipulating the activation of a proposed cognitive goal, (2) presenting an "unrelated" cognitive task that participants anticipate would either satisfy or dissatisfy the activated cognitive goal, (3) interrupting the cognitive task while creating a distraction, and (4) observing participants' choices to resume or abandon the interrupted task. The underlying premise of the protocol is that participants would be more likely to resume an interrupted task if the task is perceived as an opportunity to satisfy the activated cognitive goal; therefore, a higher resumption rate in this condition provides empirical evidence that the proposed cognitive goal is indeed being actively pursued.

When implementing the protocol, participants are told that they will be completing three supposedly unrelated tasks. In reality, participants complete the first task but then have to choose between doing only the second or third task. In addition, the tasks are actually related, and each task serves an important purpose for the experiment. The first task manipulates cognitive goal activation. The second task (which is interrupted) manipulates whether or not that task is expected to satisfy the activated cognitive goal. The third task serves as an attractive alternative for when participants later choose between completing only the second task (resuming the interrupted task at the cost of a more enjoyable task) or completing only the third task (abandoning the interrupted task for a more enjoyable task). The interruption introduced at the beginning of the second task involves typing nonsense words. While participants are warned about this interruption at the beginning of the overall session, they are also told that the timing will be random. This is to enhance the feeling of disruptiveness.

While this protocol can be adapted to test the activation of a variety of cognitive goals, the example of a recent study, which tested whether causal uncertainty (i.e., uncertainty about why something happened) activates a goal to think more abstractly11, is used here in an attempt to provide more details and contextual background on the protocol. The theory was proposed and demonstrated as an extension of prior work showing that abstract thinking (considering central, overarching themes and similarities across events as opposed to peripheral, lower-level details and differences between events) reduces causal uncertainty24. As individuals recurrently experience the benefit of abstract thinking, they develop a tendency to activate a goal to think more abstractly when experiencing causal uncertainty. The survey is available online34.

Protocol

This research was approved with a full waiver of informed consent by the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board (IRB 2011-02-0021).

1. Beginning and Introducing the Session

- Ask participants to begin the session online.

NOTE: The session can take place in a lab or on participants' own computers (desktop or laptop) outside the lab. The study requires a digital survey platform that has a time-based automatic proceeding feature (e.g., Qualtrics). - Ask participants to read basic descriptions of the overall survey procedure (e.g., expected duration, required survey-taking device, and anonymity of responses) and an online consent form, if applicable. Ask participants to click the "Continue" button at the bottom of the screen to proceed when ready.

2. Foreshadowing the Interruption and Providing Task Overview

- Present participants with the "Important Notice" message on the screen (Figure 1). Use the notice to inform participants that, at some point during the session, they will be interrupted briefly but suddenly by the "Natural-Typing Task," designed to measure participants' natural typing speeds. Inform participants that this task will involve typing 49 nonsense words with no meaning (e.g., tregran or mip).

- Below the notice, present a question asking whether the participants have carefully read all the information about the interruption. Ask participants to select "Yes" and click the "Continue" button to proceed to the next page.

Figure 1. Informing Participants about a Future Interruption. Participants are informed that they will suddenly be interrupted sometime during the session with a "Natural-Typing Task." Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- On the next page, present an overview of the three tasks that participants will supposedly be doing (Figure 2). Provide a brief description and the expected duration of each task. Ask participants to click the "Continue" button after reading the overview information to proceed to the next page.

NOTE: It is critical that the expected duration information is consistent, because participants will later choose between completing either the second task or the third task.

Figure 2. Task Overview. Participants are shown an overview of all tasks that they would possibly be completing. The expected duration is provided and kept constant so that it does not affect participants' choices later, when they have to choose between the second and third tasks. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Activation of the Proposed Cognitive Goal

- Inform participants that they will now start the "Relationship Conflict Task," and have them click the "Continue" button to proceed.

NOTE: The purpose of the first task is to manipulate the presence or absence of a cognitive goal. In the work by Namkoong and Henderson11, the "Relationship Conflict Task" was designed to manipulate either high or low causal uncertainty, because it was proposed that this would activate or not activate a goal to think more abstractly. The following steps use this particular procedure as an example. - Ask participants to recall a recent relationship conflict they had with someone they are close to. Use an open-ended format (i.e., "What was the conflict about?").

- Below the open-ended question, ask questions about this incident, such as who the conflict was with and how intense the conflict was. Then, ask participants to click the "Continue" button to proceed to the next page.

NOTE: The reason for asking questions about the recalled incident is to ensure that participants come up with a specific conflict (as opposed to general dissatisfaction) in a relationship.

- Below the open-ended question, ask questions about this incident, such as who the conflict was with and how intense the conflict was. Then, ask participants to click the "Continue" button to proceed to the next page.

- Manipulate high or low causal uncertainty by asking participants to elaborate on the recent relationship conflict, with a focus on high or low causal uncertainty, respectively (Figure 3). Ask participants to type their responses inside a textbox and, when finished, click the "Continue" button to proceed to the next page.

- Ask manipulation check questions (i.e., experienced causal uncertainty).

- Specifically, ask participants to use seven-point scales to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following two statements: "I feel like there are many things about this conflict that I still don't fully understand" and "I feel like I have a very good understanding about why the conflict happened" (reverse-coded) before clicking the "Continue" button to go to the next page.

Figure 3. Instructions in the High Versus Low Causal Uncertainty Conditions. In the high causal uncertainty condition (top), participants are asked to write about the things they do not understand about the conflict in terms of why it happened. In the low causal uncertainty condition (bottom), participants are asked to write about the things they understand well about the conflict. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

4. Manipulating Expectations to Satisfy the Cognitive Goal

- Inform participants that they will now start the "Picture Impression Task" and have them click the "Continue" button to proceed.

NOTE: To test the activation of an abstract thinking goal, the "Picture Impression Task" and the description shown to participants involve either abstract thinking (i.e., similarity-focus; expected to satisfy the cognitive goal) or concrete thinking (i.e., difference-focus; expected to dissatisfy the cognitive goal) based on prior work25,26 and a pilot study result11. - Describe to participants what the "Picture Impression Task" entails. In the similarity-focus (difference-focus) condition, inform participants that they will see five pairs of pictures and that, for each pair, they must identify one thing that makes the pictures similar to (different from) each other (Figure 4). Ask participants to click the "Continue" button to proceed to the next page after reading the descriptions.

- Show participants an incomplete image to make the screen appear as if the first pair of pictures of the "Picture Impression Task" is being loaded, without showing any parts of the pictures (Figure 5). After 2 – 3 s, have the screen automatically proceed to a different page to start the task interruption procedure.

Figure 4. "Picture Impression Task" Instructions in the Similarity- Versus Difference-Focus Conditions. In the similarity-focus condition (top), participants are told that they will be looking for similarities between pictures; in the difference-focus condition (bottom), participants are told that they will be looking for differences between pictures. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5. Loading Images. Participants see a screen that is apparently loading the first pair of pictures. This figure belongs to the similarity-focus condition. It is important to note that, before any parts of the pictures appear, participants are interrupted and their screen changes to the "Natural-Typing Task" screen shown in Figure 6. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

5. Task Interruption

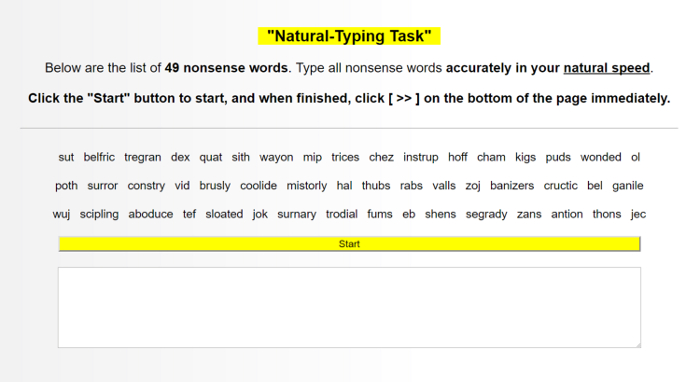

- Instruct participants to complete the "Natural Typing Task" by clicking the "Start" button, typing the 49 nonsense words presented on the screen, and clicking the "Continue" button when finished (Figure 6).

NOTE: Researchers should record the duration of the interruption (i.e., how much time participants spent on the interruption page typing the words on the screen) to check if it varied as a result of any of the manipulations. Interruption duration should also be considered as a control variable in the main analyses because it can affect task resumption rate27.

Figure 6. Task Interruption. Participants are interrupted with the "Natural-Typing Task." Here, they are asked to type 49 nonsense words so the researchers can measure their natural typing speed. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

6. Task Resumption as a Dependent Variable

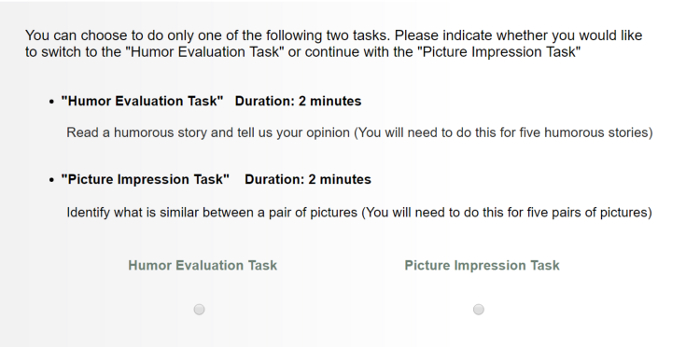

- Inform participants that, instead of completing all tasks as originally planned, they must choose between the second task and the third task. Specifically, instruct participants to choose between resuming the interrupted "Picture Impression Task" (which means giving up the "Humor Evaluation Task") or completing the "Humor Evaluation Task" (which means abandoning the "Picture Impression Task").

NOTE: The dependent variable observed is the rate of task resumption. The premise is that participants will be more likely to resume the interrupted task at the cost of engaging in a more enjoyable alternative if the interrupted task is perceived as an opportunity to satisfy the active cognitive goal.- On the same screen, show the task descriptions (Figure 7). Remind participants that both tasks will 2 min and will involve five trials (five pairs of pictures or five humorous stories, depending on the condition) to prevent them from choosing the task that simply seems easier or quicker to finish.

NOTE: A pilot test should be performed to verify that the third task is indeed expected by participants to be more enjoyable than the second task in the absence of the cognitive goal11. This will also help to avoid a ceiling effect, which is a potential concern because task-resumption motivation is generally high, even without the activation of a particular cognitive goal, as demonstrated by Zeigarnik28.

- On the same screen, show the task descriptions (Figure 7). Remind participants that both tasks will 2 min and will involve five trials (five pairs of pictures or five humorous stories, depending on the condition) to prevent them from choosing the task that simply seems easier or quicker to finish.

Figure 7. Recording Task Resumption. Participants are told that they can now do only one of the two remaining tasks. They can either resume the "Picture Impression Task" (and not the "Humor Evaluation Task") or jump to the "Humor Evaluation Task" (and abandon the "Picture Impression Task"). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

7. Concluding the Session

- Conclude the session by allowing the participants to complete the task of their choice and by asking demographics questions of interest. Debrief the participants.

NOTE: The dependent variable data was collected in the previous stage, so the actual task activities (how participants answer questions in the "Picture Impression Task" or the "Humor Evaluation Task") are no longer relevant from an empirical perspective, as long as the tasks appear realistic to participants.

Representative Results

The above method was implemented by Namkoong and Henderson11 in their first study, which consisted of two data sets. The two data sets were combined for the analysis because the pattern of results was consistent across both. Participants were 297 college students from two different public universities (168 females; age range 17 to 48 years, mean (M) age = 20.43 years, standard deviation (SD) = 3.78 years), and they completed the survey in exchange for extra course credit.

To examine whether the manipulation of causal uncertainty was successful, we averaged participants' responses to the two questions on experienced causal uncertainty (see protocol step 3.4). A t-test result showed that the manipulation was successful, as participants in the high causal uncertainty (HCU) condition experienced more causal uncertainty (MHCU = 3.32, SDHCU = 1.55) than those in the low causal uncertainty (LCU) condition (MLCU = 2.54, SDLCU = 1.35; t(295) = 4.64, p < 0.0001, d = 0.54). The amount of time participants spent completing the "Natural-Typing Task" ranged from 47 s to 240 s, with an average of 112 s (SD = 39 s). An ANOVA test revealed that participants' typing time did not vary as a function of any of the manipulated variables or their interaction (ps > 0.3). Overall, 69% of the participants resumed the interrupted task.

To recap, the experiment was a 2 (causal uncertainty: low versus high) x 2 (task construal: difference-focus versus similarity-focus) between-participants design. Both manipulated factors were effect-coded for analysis. Specifically, for the causal uncertainty factor, low causal uncertainty (N = 149) was coded as -1 and high causal uncertainty was coded as 1 (N = 148). For the task construal factor, the difference-focus was coded as -1 (N = 146) and the similarity-focus was coded as 1 (N = 151). Since the dependent variable was binary (0 if the task was abandoned and 1 if the task was resumed), a binary logistic regression analysis was performed with both manipulated factors and their interaction term as predictors.

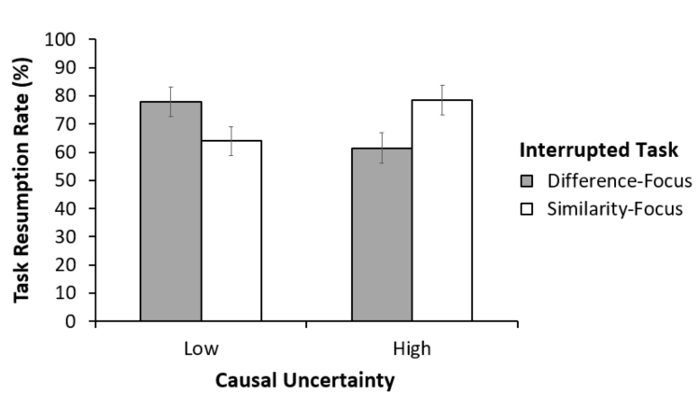

The analysis revealed that the interaction term, which was the main variable of interest, had a coefficient (B) of 0.377 with a standard error (SE) of 0.13 and had a significant impact on task resumption rate, as indicated by the Wald chi-square value35 (Wald) of 7.98 and the 2-tailed p-value (p) of 0.005. Only the interaction term was significant in the model. As predicted, in the high causal uncertainty condition, a significantly larger number of participants resumed the task in the similarity-focus condition (78.46% resumption rate) compared to the difference-focus condition (61.45% resumption rate). A simple effects analysis revealed that this difference was statistically significant (B = 0.41, SE = 0.19, Wald = 4.82, and p = 0.03). In the low causal uncertainty condition, there was a marginally significant effect in the opposite direction, as the task resumption rates for participants in the similarity-focus and difference-focus conditions were 63.95% and 77.78%, respectively (B = -0.34, SE = 0.19, Wald = 3.24, and p = 0.07). Figure 8 shows the task resumption rate for each condition. See a discussion about this finding in Namkoong & Henderson11.

Figure 8. Causal Uncertainty x Task Construal on Task Resumption Rate. A binary logistic regression revealed a significant interaction between causal uncertainty and task construal in predicting the rate of task resumption. This chart shows how the percentage of participants that resumed the task is affected by the interaction. Specifically, in the high causal uncertainty condition, the task resumption rate was greater if the interrupted task was about similarity (versus difference) focus. The effect of task construal or focus was not significant in the low causal uncertainty condition. The error bars represent the standard errors. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

In sum, participants' task resumption patterns differed between the high (versus low) causal uncertainty conditions. With greater causal uncertainty, the task resumption rate for the similarity-focus task became higher, while that for the difference-focus task became lower. Because similarity-focus coincides with abstract thinking and difference-focus coincides with concrete thinking, the demonstrated results support the proposed theory that causal uncertainty activates a goal to think more abstractly.

Discussion

The methodology detailed in this paper allows researchers to test the activation and pursuit of a cognitive goal in a simple and economical way. It is especially suitable for automatic cognitive goals because automatic goal pursuit is more efficient29, and the typing interruption (i.e., the "Natural Typing Task") prevents goals from being fulfilled through unconscious cognitive processes. Cognitive goals that are activated outside of participants' awareness are also less susceptible to demand effects.

Some of the critical considerations in adapting and implementing this protocol relate to task selection. Researchers should make sure that the second, interrupted task is seen as an opportunity to satisfy or not satisfy the cognitive goal being tested. The second task should also be free of confounds so that participants are not resuming the task to satisfy a related goal that is not the goal of research interest. For example, participants experiencing high causal uncertainty may resume the task to satisfy a mood-enhancement goal (rather than an abstract thinking goal); thus, it is critical to show that similarity focus is not seen as more enjoyable than difference focus when introducing the "Picture Impression Task." It is also important that the interruption task is not seen as an opportunity to satisfy the cognitive goal being tested; this may be a relevant concern if the goal being tested relates to a need for completion or achievement because, if participants feel satisfied as a result of the interruption task, the resumption rate will decrease when, in fact, it should increase to demonstrate goal activation with this protocol. The same logic applies when choosing the third task in the participants' list, because that task is the participants' alternative to resumption.

The appropriate tasks have been suggested by prior work and can be evaluated through pilot testing. For example, Namkoong and Henderson11 ruled out these concerns and potential alternative explanations by conducting a pilot test, which showed that the similarity-focus "Picture Impression Task" was perceived to be more difficult than both the difference-focus task and the "Humor Evaluation Task." In addition, the similarity-focus task was not seen as any more enjoyable than the difference-focus task but was seen as significantly less enjoyable than the "Humor Evaluation Task." Furthermore, if anything, the typing interruption should have decreased the resumption rate in the high (versus low) causal uncertainty condition if completing the typing task provides a sense of satisfaction. However, in the focal comparison, which is among the similarity-focus conditions, task resumption increased with higher causal uncertainty, demonstrating the pursuit of an abstract thinking goal.

It is also important to design the experiment so that participants whose cognitive goal is activated only have the expectation to fulfill the goal, but not the actual opportunity to do so before or during the interruption period. This is why, in the "Picture Impression Task," no areas of the pictures are shown to participants before the interruption and also why the interruption involves cognitive distraction.

Theoretically, a variety of cognitive goals can be activated and tested by adjusting the protocol. Studies on cognitive motivations, such as the need for cognitive closure30,31 or the need for cognition32, or creativity motivations33 have examined the constructs by measuring them at the individual level as antecedents or consequences. However, temporarily activating these cognitive motivations may allow researchers to observe the associated effects without the concern of confounding variables. The current protocol can be used as a manipulation check or an empirical test to verify the activation of the cognitive goal of interest. For example, to adapt this protocol for a research question about whether an external factor activates a need for cognition, the first task can manipulate the external factor and the second task can be a series of puzzle-solving activities where the puzzles are explained to participants as involving complex cognitive thinking (perceived goal satisfaction potential) versus emotional intelligence (perceived lack of goal satisfaction potential). Individual-level factors may also be measured and used as a moderator to see whether the cognitive goal being tested by the protocol is activated differentially depending on personal traits.

Beyond academia, practitioners in various fields who are interested activating cognitive goals may also find this protocol valuable. For example, marketers, managers, politicians, and educators often try to influence consumers, employees, constituents, and students, respectively, to adopt a certain mindset or to develop a particular way of thinking. For instance, if a manager wants to know whether a new training program facilitates a creativity motivation amongst employees, the idea may be tested by manipulating the extensiveness of the training program and then subsequently introducing a task that is seen as a creative (versus non-creative) activity, only to interrupt the task and measure the resumption rate afterwards.

A potential limitation of the protocol is the necessary adaptation that must take place to fit specific research needs. Depending on the cognitive goal being tested, a significant adjustment may be required to adapt the protocol, and these adjustment decisions should be based on theory and prior research, as well as on findings from carefully designed pilot tests. However, with proper adjustments, the protocol is highly versatile and can be applied to a wide range of academic and applied contexts, as discussed above. Another limitation of the protocol is that it does not allow researchers to measure the strength of goal activation, because the dependent variable is a binary decision outcome. To understand goal strength, researchers could potentially manipulate the severity or duration of the interruption to compare task resumption rates between conditions.

Divulgations

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements.

Materials

| Computer | N/A | N/A | The survey requires a computer and cannot be implemented using a paper-and-pencil format. |

| Qualtrics Insight Platform | Qualtrics | N/A | Qualtrics is only one example. Both online and offline survey platforms are appropriate as long as a time-based automatic proceeding feature is available. |

| IBM SPSS Statistics | IBM Corporation | N/A | Other statistical software may be used. |

References

- Amir, O., Ariely, D. Resting on laurels: The effects of discrete progress markers as subgoals on task performance and preferences. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 34 (5), 1158-1171 (2008).

- Koo, M., Fishbach, A. Dynamics of self-regulation: How (un) accomplished goal actions affect motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94 (2), 183-195 (2008).

- Locke, E. A., Latham, G. P., Erez, M. The determinants of goal commitment. Acad. Manage. Rev. 13 (1), 23-39 (1988).

- Fishbach, A., Eyal, T., Finkelstein, S. R. How positive and negative feedback motivate goal pursuit. Soc. Person. Psychol. Compass. 4 (8), 517-530 (2010).

- Zhang, Y., Fishbach, A., Dhar, R. When thinking beats doing: The role of optimistic expectations in goal-based choice. J. Cons. Res. 34 (4), 567-578 (2007).

- Förster, J., Liberman, N., Friedman, R. S. Seven principles of goal activation: A systematic approach to distinguishing goal priming from priming of non-goal constructs. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11 (3), 211-233 (2007).

- Förster, J., Liberman, N., Higgins, E. T. Accessibility from active and fulfilled goals. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 41 (3), 220-239 (2005).

- Gollwitzer, P. M., Moskowitz, G. B., Higgins, E. T., Kruglanski, A. W. Chapter 13, Goal effects on action and cognition. Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. , 361-399 (1996).

- Hassin, R. R., Aarts, H., Eitam, B., Custers, R., Kleiman, T., Morsella, E., Bargh, J. A., Gollwitzer, P. M. Chapter 26, Non-conscious goal pursuit and the effortful control of behavior. Oxford Handbook of Human Action: Social Cognition and Social Neuroscience. 2, 549-566 (2009).

- Bargh, J. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., Lee-Chai, A., Barndollar, K., Trötschel, R. The automated will: Nonconscious activation and pursuit of behavioral goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81 (6), 1014-1027 (2001).

- Namkoong, J. -. E., Henderson, M. D. Wanting a bird’s eye to understand why: Motivated abstraction and causal uncertainty. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 64, 57-71 (2016).

- Kunda, Z., Sinclair, L. Motivated reasoning with stereotypes: Activation, application, and inhibition. Psychol. Inq. 10 (1), 12-22 (1999).

- Nickerson, R. S. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2 (2), 175-220 (1998).

- Agrawal, N., Maheswaran, D. Motivated reasoning in outcome-bias effects. J. Cons. Res. 31 (4), 798-805 (2005).

- Amabile, T. M. Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. Cal. Manag. Rev. 40 (1), 39-58 (1997).

- Chiu, C. -. Y., Morris, M. W., Hong, Y. -. Y., Menon, T. Motivated cultural cognition: The impact of implicit cultural theories on dispositional attribution varies as a function of need for closure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78 (2), 247-259 (2000).

- Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L. When similarity breeds content: Need for closure and the allure of homogeneous and self-resembling groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83 (3), 648-662 (2002).

- Shah, J. Y., Kruglanski, A. W., Thompson, E. P. Membership has its (epistemic) rewards: Need for closure effects on in-group bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75 (2), 383 (1998).

- Neuberg, S. L., Judice, T. N., West, S. G. What the Need for Closure Scale measures and what it does not: Toward differentiating among related epistemic motives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72 (6), 1396-1412 (1997).

- Martin, L. L., Tesser, A., Moskowitz, G. B., Grant, H. Chapter 10, Five markers of motivated behavior. The psychology of goals. , 257-276 (2009).

- Kouider, S., Andrillon, T., Barbosa, L. S., Goupil, L., Bekinschtein, T. A. Inducing task-relevant responses to speech in the sleeping brain. Curr. Biol. 24 (18), 2208-2214 (2014).

- Walker, M. P., Stickgold, R. Sleep, memory, and plasticity. Annual Review of Psychology. 57, 139-166 (2006).

- Stickgold, R., Walker, M. To sleep, perchance to gain creative insight. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8 (5), 191-192 (2004).

- Namkoong, J. -. E., Henderson, M. D. It’s simple and I know it! Abstract construals reduce causal uncertainty. Soc. Psychol. Person. Sci. 5 (3), 352-359 (2014).

- Fujita, K., Roberts, J. C. Promoting prospective self-control through abstraction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46 (6), 1049-1054 (2010).

- Burgoon, E. M., Henderson, M. D., Markman, A. B. There are many ways to see the forest for the trees: A tour guide for abstraction. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8 (5), 501-520 (2013).

- Altmann, E. M., Trafton, J. G. Memory for goals: An activation-based model. Cogn. Sci. 26 (1), 39-83 (2002).

- Zeigarnik, B. Das Behalten erledigter und unerledigter Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung. 9, 1-85 (1927).

- Bargh, J. A., , ., , . The four horsemen of automaticity: Intention, awareness, efficiency, and control in social cognition. Handbook of Social Cognition. 1, 1-40 (1994).

- Webster, D. M., Kruglanski, A. W. Cognitive and social consequences of the need for cognitive closure. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 8 (1), 133-173 (1997).

- Kruglanski, A. W., Webster, D. M. Motivated closing of the mind: ‘Seizing’ and ‘freezing’. Psychol. Rev. 103 (2), 263-283 (1996).

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Feinstein, J. A., Jarvis, W. B. G. Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychol. Bull. 119 (2), 197-253 (1996).

- Birdi, K. S. No idea? Evaluating the effectiveness of creativity training. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 29 (2), 102-111 (2005).

- . Qualtrics Survery Software Available from: https://mccombs.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_dnDvKjR8hO5qP0V (2017)