Online Explorative Study on the Learning Uses of Virtual Reality Among Early Adopters

Summary

This article describes the profile of Spanish early adopters of virtual reality and their interests and preferences regarding learning and educational applications for this technology. To this aim, we designed an online questionnaire and interviewed 117 users of the main virtual reality forum on the Internet.

Abstract

Virtual reality (VR) has shown great educational potential because it makes it possible to simulate any desired situation or event, thus playing an important role in addressing current educational challenges. Despite the unlimited learning possibilities that VR may offer, unless users are willing to apply virtual devices to education, the investment of time, money, and effort will be fruitless. It is therefore crucial to assess the educational interest of the first generation of VR users and to identify their current needs. To this end, in this study we designed an online questionnaire and applied it through the SaaS (Software as a service) of a private server. The sample consisted of 117 early VR adopters recruited via a main portal of communication and information technologies in Spain. In order to engage participants, we posted a thread in the main forum, which is dedicated to the advances and potential uses of VR. Once the responses were gathered, we analyzed the relationship between 12 variables (mean contrasts with Snedecor's F, and contingency analysis with chi-square and Sommer's d). The results showed that the current profile of a VR user is a male over 35 years old, with university studies, and who has purchased his viewer recently (<1 year). As for the learning and teaching applications that these users were interested in, only 13.7% of the participants in this study use VR for educational purposes, although 28.2% were interested, indicating that perhaps the lack of applications or learning experiences may be hampering the use of VR within education. Almost half of the early adopters surveyed would like to learn using VR technology and are somehow optimistic about the relationship between VR and education, particularly those who are younger.

Introduction

Information and communication technologies are evolving rapidly to make it easier for human beings to communicate and relate to each other, and the distance and time that someone needs to contact and interact with someone else is reduced. However, this connection, when made through technology, is still much poorer and limited than face-to-face contact1.

VR provides a major advance in simulating physical experiences, allowing us to interact within a computer environment that feels real, giving us a sense of presence and closeness. This is one of the main reasons why VR occupies a privileged place in the plans of technology development of important companies. However, if they want to meet the needs of their potential customers, research on VR is essential to accomplish this goal2.

In Spain, as in most Western societies, the emergence of the first commercial head-mounted displays (HMD) capable of providing acceptable immersion experiences3 increased the interest in VR, leading to the development of software and VR experiences. For instance, some of the most important VR studies are currently Spanish, such as Vertical Robot, awarded multiple times for its products4, or the Tessera Studios and Dual Mirror Games, all of them of international prestige. The educational and scientific spheres have also experienced a whole explosion of research and applied educational experiences from 2015 onwards, as shown in the review by Aznar-Díaz, Romero-Rodríguez, and Rodríguez-García5.

Most universities are already aware of the crucial role that VR will play not only in the business and industry sector, but also in many scientific disciplines. Therefore, they are working on several research and innovation lines. For example, the Alfonso X el Sabio University is a pioneer worldwide in the use of VR simulation and augmented reality for training future doctors at the "UAX Virtual Simulation Hospital", unique in the world. Furthermore, this university applies VR in social, psychological, and educational research6.

Since the popularization of the Internet a few decades ago, different educational methodologies have evolved towards the so-called e-learning that a growing number of universities are adopting7,8. This online learning system is aimed at developing distance learning through technological means, some of which were developed specifically for it, while others were incorporated and adapted for educational purposes. However, e-learning is not exempt from limitations when it comes to social interaction. In this sense, VR considerably reduces some of these shortcomings, making interaction between people easier and much more realistic than any other technology. Also, it takes advantage of all the possibilities that technology offers us, creating an almost infinite world of opportunities3. For instance, VR would allow us to travel through the universe, or along the seabed, to see dinosaurs, to observe the microscopic world, or even to live emotions associated with certain experiences and social events in a simulated way. Therefore, VR could be a vital educational resource, helping teachers in their struggle to engage students with classroom topics 9,10,11.

However, not every aspect of VR is positive, and some downsides must be considered. As mentioned above, it would be useless to develop new and educational applications for VR if the potential trainees and students were not willing to use it or preferred other forms of e-learning, which could be narrower yet more aligned with their true interests and preferences. This is why the desired relationship between VR and learning not only depends on a world of exciting possibilities, but more importantly, on building this relationship upon real social needs and demands. We must bear in mind that VR was recently targeted by companies, and that less than 1% of the total worldwide population has used it. VR is also a technology that is still in its infancy and that cannot be understood if someone has not used it. This last point explains why VR is surrounded by so many prejudices that result either from ignorance or from the social fear of novelty12,13.

To bridge this gap between potential uses of VR and actual demand, it is necessary to find out the expectations of those early adopters that purchase HMDs as soon as they are available in the market. These users are so powerfully attracted to technological innovations that they do not fear purchasing new products that may succeed or fail commercially. Therefore, unlike the rest of the population, the uncertainty that surrounds these new products does not affect them. For this reason, they are the first to discover the real possibilities of VR technology not yet established in the market. Consequently, they can provide information at a real user level, making them a valuable source for this study.

As a sampling method, we designed an online examination questionnaire that was filled out by a representative convenience sample of early adopters. Participants were recruited from a VR forum in a Spanish portal for communication and information technologies, digital leisure, and video games with more than 460,000 users and ten million monthly visits14 (Table of Materials). We created a thread that received 2,000 visits in less than 2 months. The participants who accessed the questionnaire through the hyperlink responded to all the questions raised.

So far, in Spain this is the only website with a specific VR forum and more than 400 threads. Around 76,000 early VR adopters contributed messages and posts talking about all HMDs and platforms on the market15. For this reason, it is the best place to locate a homogeneous convenience sample of early VR adopters. According to Jager, Putnick, and Bornstein16, when a subgroup is homogeneous on one or more sociodemographic factors, we can estimate results with clearer generalizability, providing more accurate accounts of population effects and subpopulation differences. It also eliminates possible biases common in heterogenous convenience sampling.

Our research goals were: (1) to study the profile of early adopters; (2) to examine the current state of VR as an educational technology, determining its degree of implementation; (3) to assess the acceptance of VR as a learning tool among early adopters.

Protocol

The protocol was submitted to the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Nebrija University, in which a group of external experts reviewed and validated the process. To be able to participate in the study, we required a written acceptance informed consent as recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki17, and it was made clear to the participants that they were not going to be involved in any experimental condition.

1. Design of the research instrument

- Design a first draft of the questionnaire to meet the goals of the study (see a sample draft of the questionnaire provided as Supplementary File 1).

NOTE: The draft is created with Microsoft Word so it can be easily shared and modified. Questions included single, multiple, and open answers that were grouped in different thematic pages:

- Page 1: Accept a written informed consent obligatorily.

- Page 2: Demographic and social data of participants.

- Page 3: Descriptive information of previous VR experience as well as frequency of usage.

- Page 4: Subjective opinions and attitudes regarding VR.

- Page 5: Beliefs about the future of VR in education3.

- Send a draft to three social scientists and experts in technology that are external to the research team. The task of this committee is to review the experimental design, including ethical aspects and study design according to scientific guidelines. Also, they must validate the tool, considering aspects such as item comprehension (both questions and possible answers) in relation to the research goals.

- Design a definitive version of the questionnaire (see Supplementary File 2), considering the suggestions made by the group of experts, so it can be submitted to a scientific and ethical committee along with a research report of the project.

NOTE: We obtained a positive evaluation both in the scientific and ethical areas of the Nebrija University committee (see the positive evaluation of the Nebrija University committee provided as Supplementary File 3). Also, there was a follow-up of the entire research process conducted by the same committee.

2. Adapting the questionnaire to the online specification of a secure server

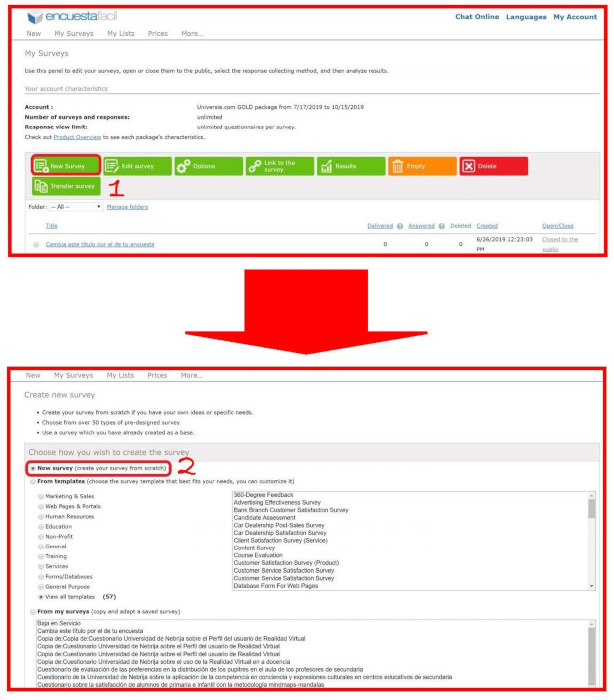

- Go to the main page of the software as a service (SaaS) with a private server (see Table of Materials) as a registered user of the platform (a registration process that must be done previously by adding personal data) and select Create your survey from scratch (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: How to create the questionnaire from scratch. (1) Click on New Survey icon; (2) Select Create Your Survey from Scratch. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

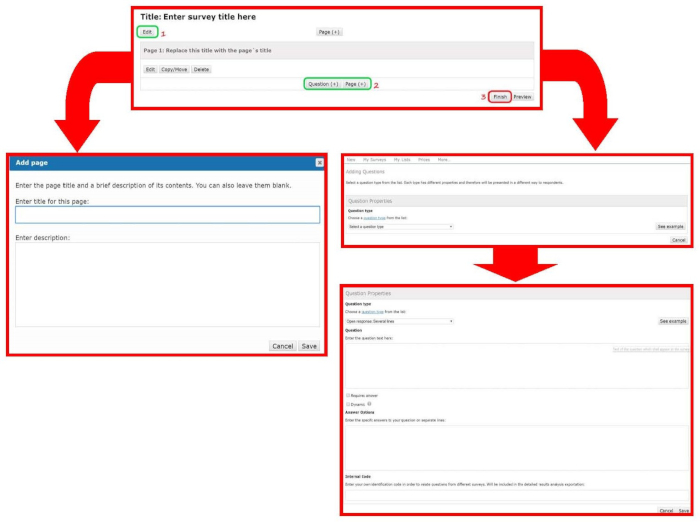

- Create several pages of the questionnaire with the questions as well as with possible answers through the SaaS with a private server.

NOTE: In this step it is important to follow the recommendations received during the validation process by the group of experts. Also, in the instructions to the participants explain the question posed correctly and the type of answer (e.g., open, closed, one- or multiple-choice, etc.) that must be filled out (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: How to design the questionnaire. (1) Edit the survey; (2) Add and configure pages and questions; (3–5) Develop pages, questions, and answers. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

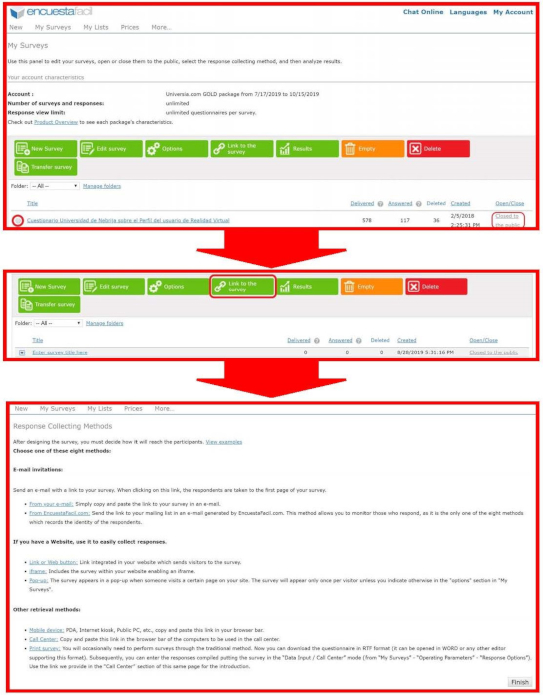

- Once the survey is created and saved (see the final questionnaire in Supplemental File 2), return to the main menu of the platform, select the questionnaire, and click on the icon Open | Close Public Survey to make it available to participants. After that, click on the icon Obtain a Link to the Survey, choosing one of several options by which participants will access the survey (e.g., a link embedded in an email or in a website, an iframe in a website, a pop up in a website, a link to computers of a call center, see Figure 3).

NOTE: The criterion to develop the final tool were that (1) the questionnaire had to be completed with any electronic device with Internet access (e.g., tablets, personal computers, smartphones); (2) participants had to fill out the questionnaire just one time (to this end, the chosen system must be able to keep the information of users who have already participated by identifying the IP of the device that was used to access and complete the survey); (3) the selected system had to guarantee the anonymity of the participants at all times, allowing the data to be stored on a secure private server.

Figure 3: How to obtain a link to the survey. (1) Open the survey; (2) Click on Obtain a Link to the Survey icon; (3) Select the chosen method. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Sampling method

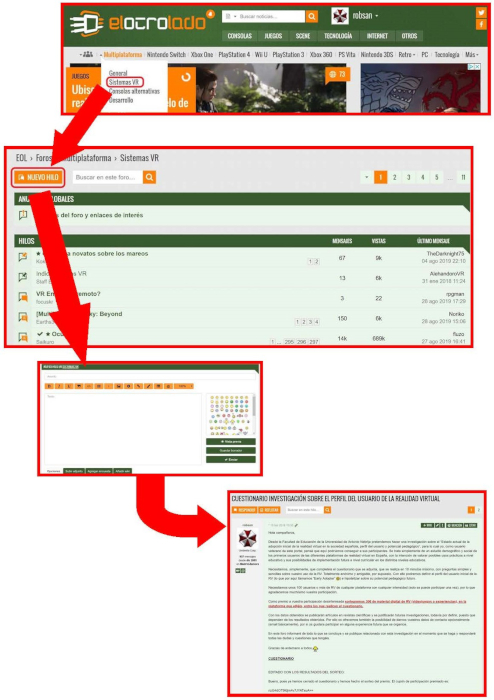

- Go to the internet portal as a registered user (registration that must be done before completing all the personal data) and create a thread in the VR forum to detail the study (see Table of Materials). Post a hyperlink to the survey hosted in the online private server (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: How to launch a thread in the VR forum. (1) Click on the Sistemas VR icon; (2) Click on NUEVO HILO icon; (3,4) Write a post with the questionnaire link included. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

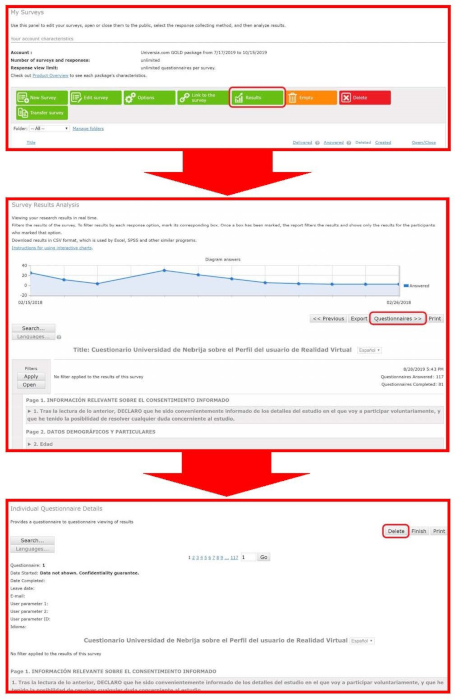

- Go to the main page of the SaaS as a registered user of the platform, select the questionnaire created, and click on Ergebnisse. On the pop-up menu, click on the icon Questionnaire to access the filled-out questionnaires directly. Eliminate all the incomplete or erroneous questionnaires through the SaaS (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: How to eliminate all the incomplete or erroneous questionnaires. (1) Click on Ergebnisse icon; (2) click on Export icon; (3) Eliminate all the incomplete or erroneous questionnaires. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Once the questionnaires reach the minimum number of participants (>100) after excluding incomplete questionnaires, go to the main page of the SaaS as a registered user of the platform, select the questionnaire, and click on the icon Open/Close Public Survey to finish the survey, so no one else can participate again (see step 1 in Figure 3 again).

NOTE: The participants of this study were 117 VR users (21 females and 96 males) who owned a VR HMD (any available in Spain). Note that the final sample of 117 participants resulted from a screening and filtering of 578 questionnaires, of which we excluded many undelivered cases, as well as 36 questionnaires that were incomplete, without applying any other filter to the data. As for the mean age of the participants, μ = 36.91 years old with a standard deviation of σX = 6.39 (μ = 36.19 and σX = 7.50 for females, and μ = 37.07 and σX = 6.15 for males).

4. Statistical analyses

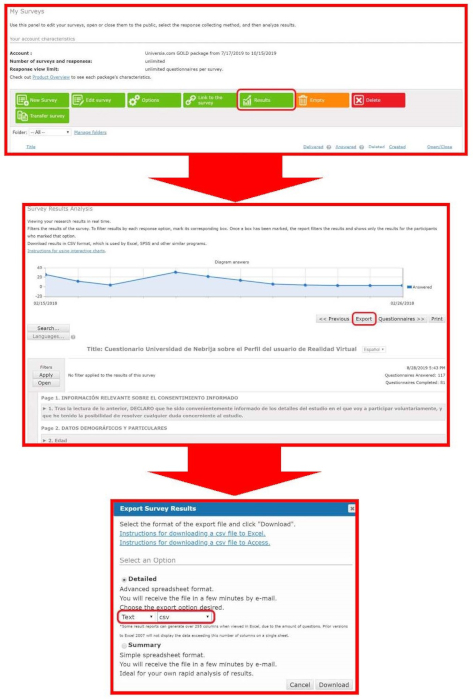

- Go to the main page of the SaaS as a registered user of the platform, select the survey created and click on the icon Ergebnisse. On the pop-up menu, click on Export and select the pop-up options of the report detailed (advanced spreadsheet format), in Text and with .csv extension (see Figure 6). Once the questionnaires are completed by the participants, export them to an email account in .csv format, so these can be kept in a safe, private, and protected place.

Figure 6: How to export data to use in the statistical software package. (1) Click on Ergebnisse icon; (2) Click on Questionnaires icon; (3) Select Text and csv in the Detailed option. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

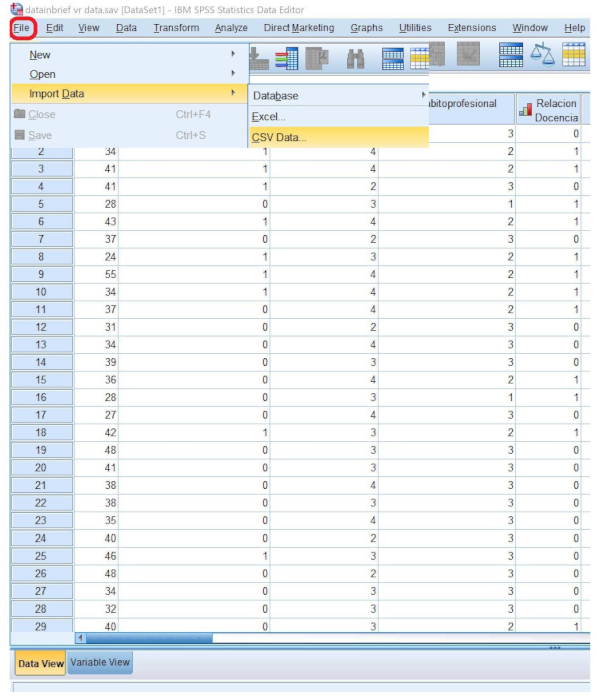

- Open the statistical software (see Table of Materials) and select File Menu | Import Data | CSV Data. Select the.csv file previously saved. This process allows transformation of the anonymous data into the analysis format required by the statistical software package (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: How to import data in the statistical software package. Select File Menu | Import Data | CSV Data. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Select the variables to analyze statistically ("Gender", "Age", "Educational Qualification", "Current Direct Relationship with Formal Education", "Previous Experiences with Sophisticated VR HMD", "Level of the Private VR HMD", "Number of Years Using VR", "Usage Frequency", "VR Usage for Educational Purposes", "Interest in VR for Educational Purposes", "Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of Virtual Reality" and "Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of Virtual Reality") and delete the rest of the information imported by the .sav file generated by the statistical software package.

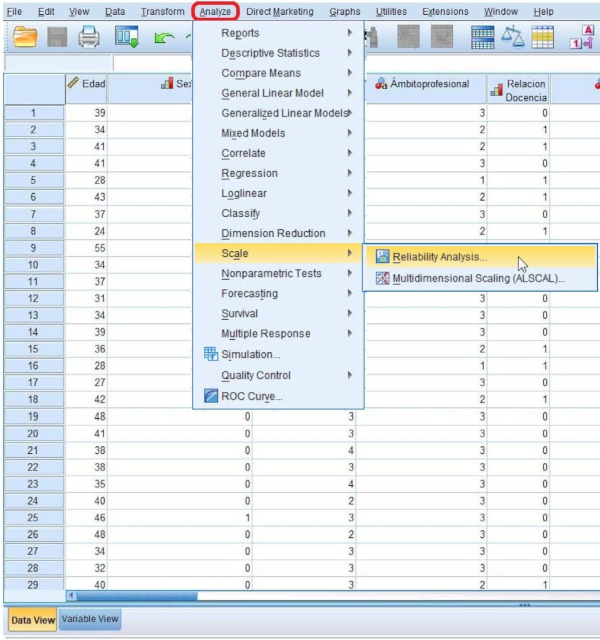

- Assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire with the Alpha's Cronbach with the statistical software package. To this end, select the Analyze Menu | Scale | Reliability Analysis, and transfer all the variables to the Reliability Analysis dialogue box. Finally, click on the OK icon to generate the desired output (see Figure 8).

NOTE: The questionnaire had a high reliability and internal consistency, measured through the Alpha's Cronbach (α = 0.826).

Figure 8: How to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire. Select Analyze Menu | Scale | Reliability Analysis. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

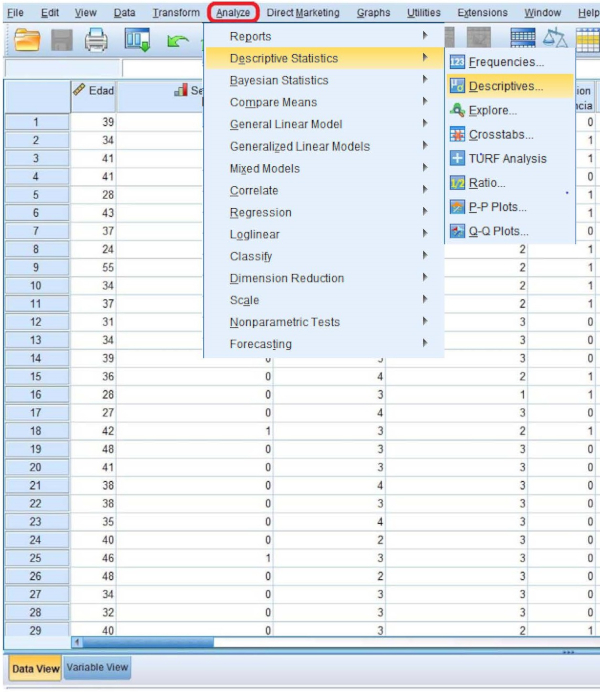

- Carry out the descriptive analysis with the statistical software package. Explore descriptive statistics such as the arithmetic mean and the standard deviation for the quantitative variable "Age". Study frequency distribution in the rest of the variables. To carry this analysis out, select Analyze Menu | Descriptive Statistics | Frequencies and, after the output, Analyze | Descriptive Statistics | Descriptive (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: How to carry out the descriptive analysis of the data. Select Analyze Menu | Descriptive Statistics | Frequencies and, after the output, Analyze | Descriptive Statistics | Descriptive. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

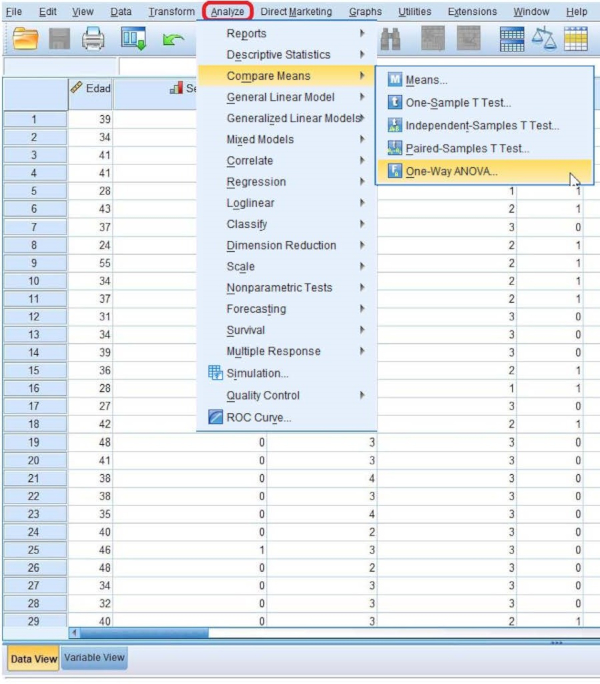

- Conduct One-Way ANOVA analysis with the statistical software package. To this end, select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | One-Way ANOVA, and in the One-Way ANOVA dialogue box put "Age" as the factor and the rest of the variables as dependent variables (see Figure 10).

NOTE: This process should be done for each of the nominal ("Gender", "Current Direct Relationship with Formal Education", "Previous Experiences with Sophisticated VR HMD", "VR Usage for Educational Purposes", "Interest in VR for Educational Purposes", "Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of Virtual Reality", and "Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of Virtual Reality") and ordinal variables ("Educational Qualification", "Level of the Private VR HMD", "Number of Years Using VR", and "Usage Frequency"). The output shows the statistical significance of "Age" as a discrete quantitative variable by comparing means with the Snedecor's F distribution (non-considering equality of variances).

Figure 10: How to conduct One-Way ANOVA analysis. Select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | One-Way ANOVA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

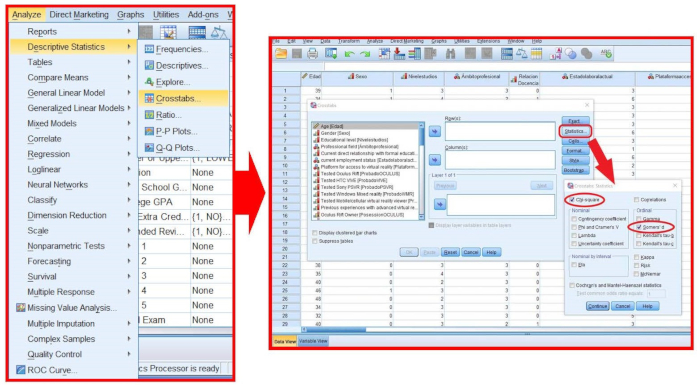

- Conduct the Chi-squared test on contingency tables to test whether or not there is a relationship between the variables, and Somers' d to reflect the strength and direction of the associations. To this end, go to Analyze menu | Descriptive Statistics | Crosstabs and, in the Crosstabs dialogue box, click on Statistik and select options Chi-squared and Somers' d and click on Weitermachen (see Figure 11).

- In the Crosstabs dialogue box, transfer one of the nominal or ordinal variables as rows and the rest as columns. This process must be repeated for each of the variables in the rows, eliminating the ones already analyzed, to obtain all the correlations between them.

Figure 11: How to conduct Chi-squared and Somers d test. (1) Select Analyze Menu | Descriptive Statistics | Crosstabs; (2) Select Chi-squared and Somers' d options. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Representative Results

Table 1 presents the frequency distribution of the categorical variables (nominal, dichotomous, and ordinal variables) along with the mean and standard deviation of the interval scale variable "Age".

| CATEGORICAL VARIABLES | |||

| Gender | Levels | Frequency | Percentage |

| It is a dichotomous variable i.e., being man or woman. | Man | 96 | 82.1 |

| Woman | 21 | 17.9 | |

| Educational qualification | |||

| Education was treated as an ordinal categorical variable following four levels: primary, secondary, university and postgraduate. | Primary | 3 | 2.6 |

| Secondary | 39 | 33.3 | |

| University | 49 | 41.9 | |

| Postgraduate | 26 | 22.2 | |

| Current direct relationship with formal education | |||

| This was treated as a Y/N dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant was either a teacher or student, and NO for the rest of cases). | None | 90 | 76.9 |

| Teacher or student | 27 | 23.1 | |

| Previous experiences with sophisticated VR HMD | |||

| Response to the question “Which kind of virtual reality platforms have you try?”. It was treated as a Y/N dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant was familiar with special viewer for video game or personal computers, and NO if s/he was only familiar with VR in mobile phones). | No | 21 | 17.9 |

| Yes | 96 | 82.1 | |

| Level of the private VR HMD | |||

| Response to the question “Which kind of virtual reality platform do you have?”. It was treated as an ordinal and categorical variable with three possible options: mobile phone, video game console and personal computer. | Mobile phone | 26 | 22.2 |

| Video game console | 54 | 46.2 | |

| Computer | 37 | 31.6 | |

| Number of years using VR | |||

| Response to the question “How long have you been using virtual reality?”. It was treated as an ordinal categorical variable with four options: less than 1 year, 1-2 years, 2-3 years and more than 3 years. | Less than one year | 72 | 61.5 |

| Between one and two years | 35 | 29.9 | |

| Between two and three years | 4 | 3.4 | |

| More than three years | 6 | 5.1 | |

| Usage frequency | |||

| Response to the question “How often do you use virtual reality?”. It was treated as an ordinal categorical variable with four options (Just occasionally, Once a week, Several times a week, and one or more daily hours). | Occasionally | 43 | 36.8 |

| Once a week | 25 | 21.4 | |

| Several times a week | 40 | 34.2 | |

| One or more hours each day | 9 | 7.7 | |

| VR Usage for educational purposes | |||

| Response to the question “In which of the following purposes do you tend to use virtual reality more?”. It was treated as a dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant uses VR for learning and gaining knowledge, and NO, otherwise). | No | 101 | 86.3 |

| Yes | 16 | 13.7 | |

| Interest in VR for educational purposes | |||

| Response to the question “Which of the following leisure genres regarding virtual reality are of your interest?”. It was treated as a Y/N dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant is interested in its educational potential, and NO, otherwise). | No | 84 | 71.8 |

| Yes | 33 | 28.2 | |

| Optimism regarding the future pedagogical possibilities of virtual reality | |||

| Response to the question “For which of the following purposes would you like to use virtual reality in the future?”. It was treated as a Y/N dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant sees her/himself in the future learning with this technology, and NO, otherwise). | No | 57 | 48.7 |

| Yes | 60 | 51.3 | |

| Optimism regarding the future pedagogical possibilities of virtual reality | |||

| Response to the question “In which areas do you forecast the future of virtual reality?”. It was treated as a Y/N dichotomous variable (YES, if the participant believes that VR will play a major role in the educational field in the next years and NO, otherwise). | No | 62 | 53.0 |

| Yes | 55 | 47.0 | |

| TOTAL | 117 | 100.0 | |

| QUANTITATIVE VARIABLES | |||

| Age | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Number of years old as an interval scale variable. | 36.91 | 6.39 | |

Table 1: Frequency distribution of the variables considered in the study. This table has been modified from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9.

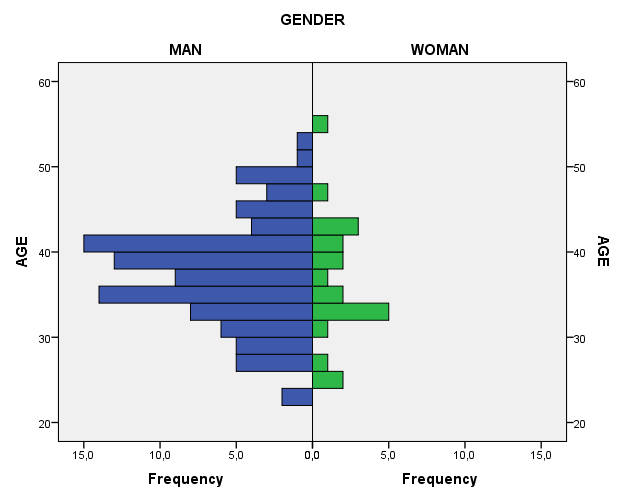

Results at first glance give us a profile of the users, shown in Table 1: males (82.1%), with university studies (64.1% postgraduates), related to education (76.9%), having previous experience with VR HMD (82.1%), who acquired a viewer during the last year (61.5%). As for the use of this technology, they were players of video game consoles VR HMD (46.2%), who use VR at least once a week (63.2%), but not for learning purposes (86.3%) and who did not seem to be interested in using this technology for learning (71.8%), although they did show interest in using it for educational purposes in the future (51.3%) despite the fact that they are not very optimistic about its future pedagogical possibilities (47%)6. Regarding the age of the participants, we can see in Figure 12 that the mean was μ = 36.91 with a standard deviation of σX = 6.39.

There were no statistically significant age and gender differences, as observed in Table 2. Only "Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of VR" varied significantly with "Age": Those who felt more optimistic about the future educational possibilities were younger (μ = 35.56 and σX = 5.74) than those who did not (μ = 38.11 and σX = 6.74)9.

Figure 12: Age and gender pyramid. This figure has been republished from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9 Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Variables | Sum of squares | df | Root mean square | F | p-value |

| Gender | 13,418 | 1 | 13,418 | .327 | .569 |

| Educational qualification | 165,879 | 3 | 55,293 | 1,367 | .256 |

| Current direct relationship with formal education | 20,616 | 1 | 20,616 | .503 | .480 |

| Previous experiences with sophisticated VR HMD | 27,568 | 1 | 27,568 | .673 | .414 |

| Level of the private VR HMD | 161,535 | 2 | 80,768 | 2,013 | .138 |

| Number of years using VR | 169,738 | 3 | 56,579 | 1,400 | .246 |

| Usage frequency | 57,568 | 3 | 19,189 | .464 | .708 |

| VR Usage for educational purposes | 51,353 | 1 | 51,353 | 1,261 | .264 |

| Interest in VR for educational purposes | 33,517 | 1 | 33,517 | .820 | .367 |

| Interest in the use of VR in formal education in the future | 4,044 | 1 | 4,044 | .098 | .754 |

| Optimism regarding the future pedagogical possibilities of VR | 189,408 | 1 | 189,408 | 4,792 | .031* |

Table 2: Age comparison of means over the rest of the variables through ANOVA test. Abbreviations, df = Degrees of Freedom; F = Snedecor's F; p-value = probability value or significance. *Comparison of means is significant at the level of 0.05. This table has been modified from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9.

Table 3 reports the values of the contingency tables using the Chi-squared test and the Somers' d, showing whether the correlations observed were significant and their direction (positive or negative).

| Gender | EQ | CRFE | PEV | LPV | YUV | UF | UEP | IEP | IUF | OFP | |

| Gender | – | 14.55** | 12.38** | 20.6** | 30.29** | 10.06* | 27.1** | 18.463** | 1.24 | .352 | .177 |

| .3** | .32** | -.42** | -.17 | -.083 | -.35** | .395** | .1 | .053 | -.038 | ||

| EQ | 14.55** | – | 15.32** | 6.70 | 13.63* | 15.37 | 17.45* | 3.62 | .25 | 3.99 | 3.2 |

| .3** | .3** | -.17* | -.17 | -.02 | -.26** | .14 | .03 | .1 | .11 | ||

| CRFE | 12.38** | 15.32** | – | 12.38** | 22.57** | 5.11 | 8.04* | 4.46* | 1.35 | .138 | .018 |

| .32** | .3** | -.32** | -.31** | -.06 | -.18* | .19 | .11 | -.03 | .0.12 | ||

| PEV | 20.60** | 6.7 | 12.38** | – | 59.88** | 1.56 | 17.82** | 4.81* | .33 | .012 | .82 |

| -.42** | -.17* | -.32** | .47** | .0.8 | .28** | -.2 | -.05 | -.01 | .08 | ||

| LPV | 30.29** | 13.62* | 22.57** | 59.88** | – | 12.02 | 31.92** | 19.07** | 2.35 | .64 | 2.06 |

| -.17 | -.17 | -.31** | .47** | .05 | .3** | -.09 | -.05 | -.03 | .11 | ||

| YUV | 10.06* | 15.37 | 5.11 | 1.56 | 12.02 | – | 23.39** | 18.18** | 6.35 | 2.88 | 5.25 |

| -.08 | -.02 | -.06 | .0.76 | .05 | .16 | .05 | .09 | -.081 | .179* | ||

| UF | 27.1** | 17.45* | 8.04* | 17.82** | 31.92** | 23.39** | – | 2.98 | 3.44 | 7,296 | 2,957 |

| -.35** | -.26** | -.18* | .28** | .3** | .16 | -.04 | .13 | -.044 | .142 | ||

| UEP | 18.46** | 3.62 | 4.46* | 4.81* | 19.07** | 18.18** | 2.98 | – | 32.18** | 4.17* | 3.52 |

| .39** | .14 | .19 | -.20 | -.09 | .05 | -.043 | .51** | .18* | .16 | ||

| IEP | 1.24 | .25 | 1.35 | .33 | 2.35 | 6.3 | 3.43 | 32.18** | – | 11.02** | 5.1* |

| .1 | .0.3 | .11 | -.05 | -.05 | .09 | .13 | .51** | .31** | .21* | ||

| IUF | .35 | 3.99 | .14 | .01 | .64 | 2.88 | 7.3 | 4.17* | 11.02** | – | 10.62** |

| .05 | .1 | -.03 | -.01 | -.03 | -.08 | -.04 | .18* | .31** | .3** | ||

| OFP | .18 | 3.2 | .02 | .82 | 2.06 | 5.25 | 2.96 | 3.52 | 5.1* | 10.62** | – |

| -.04 | .11 | .0.12 | .08 | .11 | .18* | .14 | .16 | .29* | .3** |

Table 3: Contingency table using the chi-squared test (first value in each cell) and Somers' d (second value in each cell). Abbreviations, EQ = Educational Qualification; CRFE = Current Direct Relationship with Formal Education; PEV = Previous Experiences with Sophisticated VR HMDs; LPV = Level of the Private VR HMD; YUV = Number of Years Using VR; UF = Usage Frequency; UEP = VR Usage for Educational Purposes; IEP = Interest in VR for Educational Purposes; IUF = Interest in the Use of VR in Formal Education in the Future; OFP = Optimism Regarding the Future Pedagogical Possibilities of VR. * Correlation is significant at the level of 0.05. ** Correlation is significant at the level of 0.01. This table has been modified from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9.

Notice that a number of nominal variables were recoded and given ordinal values. This was done to see the relationship between gender (male/female) and other variables. In other words, the integer given to each condition does not transform the variable into a quantitative one, but simply serves to know instantly the trend shown by the results towards one or another condition. Otherwise it would be impossible to establish if being a man or a woman was directly or indirectly associated with the rest of the variables. A similar process was done with every binary variable, giving the higher score to the category "Yes"9.

The Chi-squared test and Somers' d tests run on the contingency table outline the relationship that exists between some variables. For instance, females were educated at a higher level, a larger number of women were also related to the field of formal education, and more females reported using VR for learning purposes too. As for males, they used VR more frequently, and have tried the sophisticated VR HMDs.

A positive and significant relationship between formal education and the level of studies was found, as well as a significant and negative association between having tried a sophisticated VR HMD, viewer devices owned, and the frequency of VR usage. It was clear that the frequency of usage was significantly and directly associated to having tried a sophisticated VR HMD and to the number of viewer devices owned. The same variable was significantly and inversely associated to the educational qualification of the VR user. There was also a significant, strong, and direct relationship between having tried a sophisticated VR HMD and the number of viewer devices owned 9.

As for the variables that were directly related to the usage and inclinations for VR as a learning tool, we can see a strong and positive correlation, since a "Yes" answer to having an interest in the usage of VR as a learning tool was significantly and directly associated to learning through VR in formal education. They were also associated with currently using VR as a learning tool and being optimistic about the future educational possibilities of VR9.

The contingency table also shows a statistically significant and nonlinear (or second-degree) association with the Chi-squared analyses but not with Somers' d. This situation was due to some of the categories of a variable having a partial influence over another variable, such as "Number of Years Using VR". As for the variables that assessed which users had used VR recently, results showed that the interest in VR is still developing. More specifically, we can see that the usage frequency was high, but interest or preferences change depending on the willingness to try all the VR possibilities.

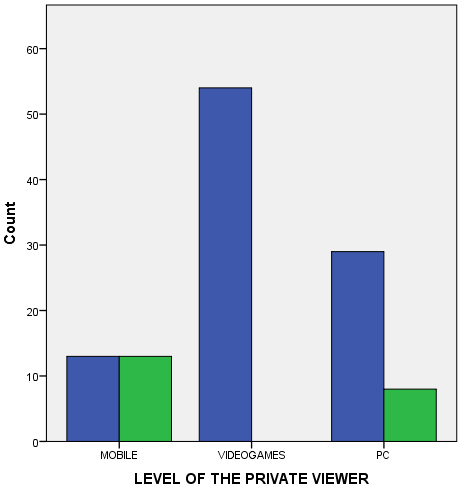

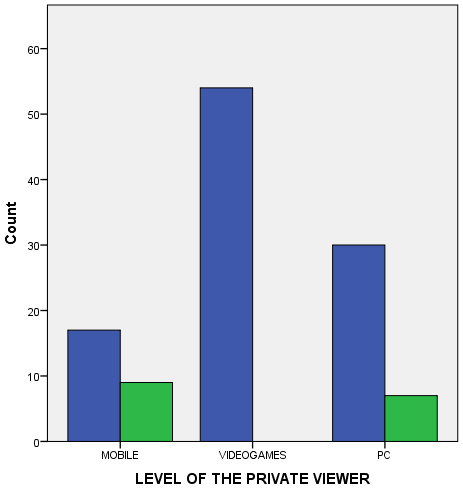

As for the "VR HMD Devices Owned" we can see gender differences in "Video Game Console" (see Figure 2), and in "Current Use of VR as a Learning Tool" (see Figure 3). Among users of game consoles VR HMD (e.g, Sony PSVR) there were no women, and they were not interested in the use of the VR as a learning tool. This points to a strong gender difference in entertainment and leisure9.

Figure 13: VR HMD devices owned and gender. Green = Woman; Blue = Man. This figure has been republished from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 14: VR HMD devices owned and current use. Green = Current use of virtual reality as a learning tool; Blue = No current use of virtual reality as a learning tool. This figure has been republished from Sánchez-Cabrero et al.9. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Supplementary File 1: Sample Draft. Please click here to view this file (Right click to download).

Supplementary File 2: Questionnaire. Please click here to view this file (Right click to download).

Supplementary File 3: Evaluation. Please click here to view this file (Right click to download).

Discussion

This study explores the profile of Spanish early adopters of VR, assessing their interest in the use of VR as a learning tool. Therefore, along with other studies, it offers a fresh perspective on the real possibilities of VR and its applications to the classroom9.

The users of VR devices live literally everywhere, so there is not a physical place to identify and locate them. For this reason, the only possible way to find them is through VR forums and websites that VR users visit to find information. In conclusion, not only did we need to use the virtual space to survey VR users, but it was also mandatory to proceed with an online questionnaire.

Finding the sample was complex because the first VR HMDs have been on the market for less than 3 years. It is worth mentioning that we should not mistake the consolidation of technology for its popularity: VR may be fairly popular despite most people having never tried it. This narrowed the population and sample to be studied. Finding VR users was another difficulty to overcome, because they form a heterogeneous group with different interests and socio-demographic characteristics and are hard to reach and locate. Also, they use different VR head-mounted displays (e.g., PlayStation VR: PSVR, Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, Windows Mixed Reality: WMR) and platforms (e.g., personal computers, Sony PlayStation 4, smartphones)9 which makes it even harder to find them.

An online questionnaire was the only possible way to examine early VR adopters' preferences and interests in the use as a learning tool, because the dispersion of users in different locations and systems makes any face-to-face consultation or any other methodology common in the social sciences, such as interviews or focus groups, impossible. However, this method is not without limitations, since the participants' answers were limited to the questions, most of which were structured.

In addition to this, the real number of Spanish VR early adopters is difficult to know because most manufacturers do not make the information about their sales public for fear of discouraging potential investors or clients. Nonetheless, we can estimate this number if we have a look at indirect sources. For instance, in 2018 less than 4 million VR HMDs were sold on the worldwide market18, which makes users of these technological applications, software, and video games less than 1% of the total population19 (i.e., approximately 42% of the worldwide population20. Therefore, less than 5 per thousand of the population can be regarded as early adopters.

One of the main implications of this study lies in the relationship between the educational field and VR, which is at a critical moment21. VR technology is now taking its first commercial steps, a fact that explains why efforts are currently directed at entertainment and leisure18,19. The results of this study show that users' interest in entertainment is much greater in VR HMDs than in video consoles (PSVR). Also, this interest is stronger in males who use their laptops or computers more frequently. As for the early adopters, learning is not a priority for them, and those who are interested find themselves with very few VR options. This can be seen, for instance, in the Oculus Store that has a very small number of VR educational applications22. Yet, its current usage is far from being insignificant, with 13.7% of use.

According to some indicators analyzed by the IDC Corporate USA21, the sales of VR devices has increased 27.2% during the first quarter of 2019 compared to the same period of 2018. This has occurred despite the fact that it was believed that the sector had stagnated. This shows how the VR industry is growing at an even faster rate than expected. And this is surely due to the existence of new viewers such as the Standalone VR HMD Oculus Quest that was launched to the market in the beginning of 2019.

Our results also indicate that interest in using VR for educational purposes is much higher than its actual use. Also, half of the users felt optimistic when asked about the educational possibilities of VR. This, along with the fact that VR is still entering education despite unideal conditions, may be taken as a positive fact. This conclusion is similar to that of Yildirim's11 or Fernández-Robles10, who also found that students were interested in the use of VR as an educational tool. According to our results it can be concluded that the lack of VR educational applications may be impeding advances and somehow affecting the interest of potential users. Consequently, the future of the relationship between education and VR may depend on the growth and evolution of new applications within this field. Without them, we run the risk of wasting an excellent opportunity.

However, how this relationship between education and virtual reality will progress in the future depends on application development and on the evolution of this sector. Our results show that, on the one hand, the lack of applications may hinder the interest of users. On the other hand, without the applications, these first opportunities could quickly disappear.

VR accessibility is another major issue, because most teachers who participated in this study showed a preference for low-cost kits and reported a sporadic use. Perhaps if costs were reduced, professionals in the educational field would prefer better equipment and would also increase the time of use, which, in turn, could change their minds about VR as a learning tool9. However, given that VR is just emerging within education, it may be too soon to make any conclusive statements. Consequently, we must wait for the consolidation of this technology if we are to make more accurate evaluations of its virtues, potentials, and shortcomings.

Offenlegungen

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very thankful to the managing team of Elotrolado.net, because without their help this study would have been impossible to conduct. We are also grateful to Encuestafacil.com, which offered us their services free of charge so that we could create the questionnaire and use their servers to gather the data. Finally, we appreciate the feedback and support received from the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Nebrija University and from Alfonso X el Sabio University.

Materials

| Encuestafacil.com Saas (Software as a Service) | Encuestafacil.com | 2019 | Software as a Service in the Encuestafacil.com private data server |

| Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) | IBM | 24 | Software package used in statistical analysis of data |

| VR Forum in Elotrolado.net online portal | New EOL, S.L. | 2019 | The elotrolado.net is a Spanish website for communication and information technologies, digital leisure and video games, with more than 460,000 users and ten million of monthly visits. So far, it is the only Spanish website with a specific VR forum with more than 400 threads. Around 76,000 early VR adopters contribute with messages and posts talking about all HMD, and platforms on the market. |

Referenzen

- Norman, K. L. . Cyberpsychology: An introduction to human-computer interaction. , (2017).

- Cipresso, P., Giglioli, I. A. C., Raya, M. A., Riva, G. The past, present, and future of virtual and augmented reality research: a network and cluster analysis of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology. 9, (2018).

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., et al. Demographic data, habits of use and personal impression of the first generation of users of virtual reality viewers in Spain. Data in Brief. 21, 2651-2657 (2018).

- Aznar-Díaz, I., Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Rodríguez-García, A. M. La tecnología móvil de Realidad Virtual en educación: una revisión del estado de la literatura científica en España. EDMETIC, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC. 7 (1), 256-274 (2018).

- Tecnología y Medicina, una fusión para mejorar la salud. El Mundo Available from: https://www.elmundo.es/promociones/native/2018/06/22 (2018)

- Kentnor, H. E. Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue. 17 (1), 21-34 (2015).

- Moreira, F., Pereira, C. S., Durão, N., Ferreira, M. J. A comparative study about mobile learning in Iberian Peninsula Universities: Are professors ready. Telematics and Informatics. 35 (4), 979-992 (2018).

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., et al. Early virtual reality adopters in Spain: sociodemographic profile and interest in the use of virtual reality as a learning tool. Heliyon. 5 (3), 01338 (2019).

- Fernández-Robles, B. Factores que influyen en el uso y aceptación de objetos de aprendizaje de realidad aumentada en estudios universitarios de Educación Primaria. Edmetic, Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC. 6 (1), 203-219 (2017).

- Yildirim, G. The users’ views on different types of instructional materials provided in virtual reality technologies. European Journal of Education Studies. 3 (11), 150-172 (2017).

- Rosedale, P. Virtual reality: The next disruptor: A new kind of worldwide communication. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. 6 (1), 48-50 (2017).

- Sherman, W. R., Alan, B. C. . Understanding virtual reality: Interface, application, and design. , (2018).

- Traffic overview of Elotrolado.net. Similarweb Available from: https://www.similarweb.com/website/elotrolado.net (2019)

- Foro de Sistemas VR in Multiplataforma. Elotrolado.net Available from: https://www.elotrolado.net/foro_multiplataforma-sistemas-vr_224 (2018)

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., Bornstein, M. H. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 82 (2), 13-30 (2017).

- WMA Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. World Medical Association Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects (2013)

- Statista. Unit shipments of virtual reality (VR) devices worldwide from 2017 to 2018 (in millions), by vendor. Technology & Telecommunications Consumer Electronics Global virtual reality device shipments by vendor 2017-2018 Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/671403/global-virtual-device-shipments-by-vendor/ (2019)

- Newzoo’s 2017 Report: Insights into the $108.9 Billion Global Games Market. Newzoo Available from: https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/newzoo-2017-report-insights-into-the-108-9-billion-global-games-market/ (2019)

- AR & VR Headsets Market Share. IDC Corporate USA Available from: https://www.idc.com/promo/arvr (2019)

- Educational experiences/apps for the Oculus Rift. Unimersiv Available from: https://unimersiv.com/reviews/oculus-rift (2019)