Loneliness Assuaged: Eye-Tracking an Audience Watching Barrage Videos

Summary

The study proposes an activation-match model to study how loneliness is mitigated when a lonely audience watches barrage videos of rational and emotional appeals. The protocol uses eye tracking to document duration and fixation, accounting for the degree of satisfaction when emotional needs are appeased by content and barrage.

Abstract

Researchers usually theorize media exposure based on assumptions of legacy media. However, a new interactive video viewing format, in this case barrage video where viewers’ comments are overlaid over visual content, challenges past perspectives. This study proposes an activation and match satisfaction model to study viewing behaviors of lonely people and to challenge previous claims. It presents a protocol to examine the mechanism of how loners use barrage videos by combining eye tracking and self-report measures. Eye tracking documents the audience's conscious and subconscious watching behaviors in real time and allows for inference of the amount of allocated cognitive resources in response to rational and emotional content. The self-report gauges the amount of satisfaction obtained. Overall, results from the measures supported an activation and match satisfaction model regarding loners and their barrage video viewing behaviors. Implications are discussed.

Introduction

Eye-tracking technique

The eye is often referred to as a window of the mind1,2. Eighty percent of human information intake is obtained visually3. Since the 19th century, people began to study human psychological activities by directly observing eye movements of participants. Miles invented the peephole to make observations when participants read4. In the study, the experimenter sat opposite a participant and observed the participant’s eye movements through a small hole in the middle of the reading material. Since then, technology has vastly improved. Currently, state-of-the-art eye-movement tracking devices mainly focus on electric current-recording, magnetic-induction and optical-recording, which includes corneal reflection and iris-scleral reflection methods5,6,7. The noninvasive features widely prevalent today make eye movement recording more natural, enhancing ecological validity. Today, eye movement techniques generally refer to the use of computer-controlled eye tracking to record and analyze the positioning of the participant's eye and the forms of eye movements during viewing of visual material.

Many theoretical perspectives regarding eye movements have matured over the years. These include the vision buffer processing model, the parafoveally processing model, the E-Z Reader model, the immediately processing model and the eye-mind processing model8,9,10. The immediately processing model holds that the processing of viewing content at all levels is not delayed, but occurs in real-time. The eye-mind processing model focuses on text information and holds that as long as one is processing a word, one would look at it. Put in another way, the word that one processes is exactly the very word one is looking at. The processing time of a word is the total fixation time of the participant’s eye.

There are three basic types of human eye movements: fixation, saccades and pursuit movements8,11,12. The fixation duration and fixation count usually reflect the extent to which the participant exerts cognitive resources to the content being viewed. Saccade refers to the movement from one gaze point to another. Retrospective saccade can be used as an indicator of the processing sophistication in the encoding process. Regression saccade indicates a deeper processing of an area after the first gaze of the key areas, reflecting the difficulty or interest of the content in that area. Pursuit movements are usually performed when there is visual noise, and the eye seeks out a point of interest.

On the other hand, we can also measure pupil size and blink frequency; both reflect people’s psychological activities13,14,15. For example, there is a relationship between pupil size and the specific task difficulty, motivation, interest, attitude, and fatigue. At present, the relationship between pupil size and emotional valence is not clear16. However, if a researcher combines pupil size with other indicators, such as electroencephalogram (EEG), the accuracy would be greatly improved17. For blink indicators, according to the hedonic-blink hypothesis, the decrease of blink frequency is usually associated with happy emotional thoughts, while the increase of blink frequency is associated with unhappy emotional states18.

The application of eye-tracking technology is extremely broad, including reading strategies, visual information processing, compulsive behaviors, to even artistic intentions. The application in the field of reading is the most mature. In communication, eye-tracking is useful in news consumption studies and advertising effectiveness research. For example, a large number of eye movement experiments have explored both exogenous and endogenous factors in advertising19,20, with the former exploring the physical characteristics of advertisements such as size, pattern, color, position, originality and repeated presentations21,22, and the latter exploring individual factors such as product involvement, product motivation, prior knowledge and brand familiarity23,24,25,26,27.

In addition, eye tracking technology is widely used in many other fields, such as human-computer interaction and usability research28,29,30,31; skills transfer32; infant and child development research33,34,35,36; marketing and online consumer behavior research37,38,39; and packaging design40,41, among others.

In addition to being used alone, eye tracking is often combined with other multimodal measurement techniques. For example, researchers can combine eye movement data with other physiological indicators such as EEG, skin electrical response, heart rate, skin temperature, facial expression, etc. In this way, users' emotional responses to different kinds of information can be studied more effectively42.

Eye movement technology can also be integrated into other technologies. For example, it is being used with augmented reality technology30. At present, the integration of eye movement technology and virtual reality (VR) technology is worthy of attention. On the one hand, such integration can promote the rapid development of VR related equipment. For example, the graphics processing unit (GPU) of most VR equipment is overburdened and consumes a lot of energy. Eye tracking technology can detect the audience's fixation point in real time. VR devices only need to focus on rendering this area and ignore other areas. This can significantly reduce power consumption and GPU rendering load. On the other hand, the combination can enhance its interaction features, and improve the immersion and involvement of VR users. For example, players can use eye movement instead of hands to complete operations in a game43. In addition, researchers can implement eye movement testing in a simulated environment. For example, in consumer behavior research, researchers do not need to take subjects to a real shopping mall or use real products, but test them in virtual research scenarios, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Virtual research scenario Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Barrage video

Barrage is a term originating from the military. In order to intercept moving targets, multiple artillery guns are used to fire and to form a curtain composed of high-density projectiles before the moving targets44. The term "barrage" is used in video viewing to describe a format and a phenomenon in which audience members of a particular video comment and displaying such comments on the video screen while watching a video, thus forming a comment wall curtain, as shown in Figure 2. This format of interacting and commenting is also referred to as overlaid comments45,46. Barrage videos first appeared on the "niconico" video website in Japan. The most popular websites in China are AcFun (Station A, www.acfun.cn) and Bilibili (Station B, www.bilibili.com). Many other streaming video sites in China, such as Youku, Tencent, LeTV and iQiyi, have also added the barrage sending and viewing functions. Barrage videos have attracted many Chinese viewers, and the attention of researchers in many disciplines.

Figure 2: Comment wall curtain Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Viewers of barrage videos can watch and interact with others by commenting to possibly meet a few psychological needs. The audience of such videos may share similarities in age, background and interests, so they may develop a sense of identity and belonging. There is research, for example, that shows AcFun and Bilibili are home to the “quadratic element” genre enthusiasts, with its audience being mainly between 17 and 25 years old47,48. These two websites have set up an extremely strict membership review system in that membership is only granted after acing an entrance exam by answering questions such as "What is the height of the heroine of the Thousands of Defenders in Hurricane Butler?" "How many cruisers have been dispatched by Gonon in the Battle of Rum?" Such criteria basically weed out most of the "heterogeneous" audience who want to "invade" the group.

Related to this study, barrage video creates a sense of crowd watching, which is particularly meaningful for lonely individuals. Because the content of the barrage is highly related to the plot, and comments are immediate responses, it gives the audience an illusion of watching with others even though they may be watching alone physically. This sense of companionship has been shown to alleviate loneliness49.

Barrage videos can also afford entertainment of a different kind in that viewers are not only consuming but also creating video content by blending sometime serious film making with fun plays. Barrage viewers can also find a sanctuary away from reality50,51 in which they can vent their anxiety and engage in emotional catharsis in a safe environment52, or showcase their personalities, demonstrate narcissism by getting others’ attention, and even bypass conformist norms in the real world53.

Viewing mechanism of lonely audience on barrage video

Barrage video viewing is an ideal platform to study media use and loneliness for its emotional support afforded by the venue. In this study, the researchers find previous conceptualizations of media exposure to be inadequate and therefore offer an activation and match satisfaction model (AMSM) to explain the psychological underpinnings of viewing barrage, especially by loners. In previous research, there are two perspectives that explain media use. The deficiency paradigm holds that loners, for lack of companionship, would devote more cognitive resources to the barrage content during watching, to seek company and to compensate loneliness. The global-use paradigm maintains that media use is prevalent, and that it satisfies generic and interpersonal needs in general. So regardless of emotional state, all viewers would pay attention to barrage, and they obtain different gratifications54. However, AMSM posits that emotional content serves to activate lonely audiences' interpersonal needs, and they would take initiatives to search for interactive and interpersonal communication elements, such as barrage content in the viewing process, and devote more attention to such components. The degree that these elements satisfy their emotional needs determines the degree of satisfaction they obtain.

In order to understand the mechanism of barrage video watching by lonely people, one needs to know the amount of cognitive resources that loners invest in different media content and how they satisfy their needs. However, such data cannot be reliably obtained by traditional participative reporting methods. Cognitive resources allocation operates consciously and subconsciously. It is a tall order that audience members articulate to which parts of content they invest more cognitive resources. To accomplish this, a suitable research methodology is needed to record the viewing process, and to distinguish the amount of attention to different parts of content, in addition to measuring the corresponding satisfaction from the viewing process.

For these reasons, this project tracked participants’ eye movements, as measurements of attention and the degree of cognitive resources allocated. The follow-up Likert scale questions were designed to measure participants' degree of satisfaction from exposure. Eye-tracking is a noninvasive technology that has high temporal and spatial resolutions, allowing recording while participants process continuous visual stimuli without distraction55,56. In this study, duration time and fixation counts are used as measures of attention. Duration time refers to the length of attention, and fixation count refers to the number of gazes at a particular area of the video material. Both of these eye movement indicators have been shown to be valid measures of processing thoroughness, reflecting the cognitive resources allocated by individuals57,58. Results of gaze probability, for example, allow researchers to infer attributes in the video that were important to the participant. For self-reported measures, the researchers use a 7-point Likert scale, asked and answered immediately after watching.

Based on arguments from previous explicated perspectives, the researchers designed a 2 (audience type) x 2 (ad appeal) x 2 (barrage) mixed experimental study and hypothesized the amount of attention that normal and lonely participants would pay to barrage video. Audience type (lonely and normal) was a between factor. Ad appeal had two levels, with either emotional ads or rational ads. Barrage also had two levels, denoting video that either had barrage or not. The last two were within subject factors. The general hypotheses were that lonely audience would pay more attention to emotional ads than to rational ads, and they would pay more attention to barrage than to non-barrage, whereas for normal audience, there was no such difference. Satisfaction ratings followed the same patterns. The Chen et al.59 original paper detailed all these hypotheses.

Protocol

This protocol adheres to the Jinan University research guidelines. As only the medical school of the university has an IRB board, no other discipline is required to have IRB approvals. However, the researchers confirm that all ethical rules and regulations were followed. The project did not pose any physical or psychological harm to participants.

1. Participant screening for the experiment

- Recruit native Chinese speakers from a southern Chinese university with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no hearing impairments nor psychiatric history.

- Measure loneliness using the third edition of the UCLA scale60,61. Categorize those who score 44 or above in the scale as the lonely group and place the rest in the normal group. In terms of gender and age distribution, the group corresponds to the demographic characteristics of barrage viewers47.

2. Stimuli construction

- Use rational appeal ads and emotional appeal ads as video stimuli. Positive emotional ads provide emotional support for lonely audiences, where rational ads do not.

- Choose ads that are standalone video pieces that do not require contextual information to comprehend. The typical ad length is also ideal for quick variations, experimental manipulations, and for eye-tracking data collection62. The length of each video is about one minute.

- To ensure that emotional and rational appeals are manipulated successfully, have people watch and rate a pool of preselected ads based on these appeals. Here, thirteen coders majoring in advertising were used.

- To maximize manipulation, choose videos with the highest scores in either categories to be the experimental stimuli. The final selected ads represented eight kinds of products. The same product has an emotional ad and a rational ad.

- Make the barrage video. There are two ways to make a barrage video for research.

- Upload the video to a barrage website, such as the B station at Bilibili (https://www.bilibili.com/). Have participants log into their accounts to watch, and comment. The uploader controls the position of the barrage, usually at the upper third of the screen.

- Alternatively, use video editing software to convert barrage into subtitles, so comments can be manually added to the video barrage area. The ready-made video can then be called in the data-collection process. This experiment used the second method.

- Produce four presentation orders for the experiment to randomize presentational effects. In this design, each participant only saw one version of a particular video, either emotional or rational appeal of an ad, and each saw eight ads altogether.

3. Eye tracking protocol

- Eye tracking procedure

- Use a commercial eye tracker in the study. Set the default setting for the tracker gaze sample rate at 60 Hz per second.

- Place a 24-inch computer screen 50 cm from the participant’s chair. Attach the eye tracker to the computer.

- Invite the participant in the lab. Ask the participant to read and sign an informed consent form. Ask the participant to sit comfortably in front of the test computer.

- Have the experimenter check, and adjust the chair height if necessary, to make sure that the TV screen is at the participant’s eye level.

- Ask participants to sit still to complete a calibration task to ensure that data collected during the experiment are accurate. Inform participant that a 5-point calibration is necessary to achieve the highest accuracy in data collection, and to track participants’ gaze within 2° of accuracy.

- Ask participant to follow a moving red dot on the computer screen with both eyes and to fixate on it when it stopped. If a participant looks away during calibration, then repeat the process.

- Check the tracker software to see if a participant misses a calibration point. If so, repeat the calibration.

- Ask the participant to click the left mouse button to start an exercise test to familiarize them with the experimental procedure.

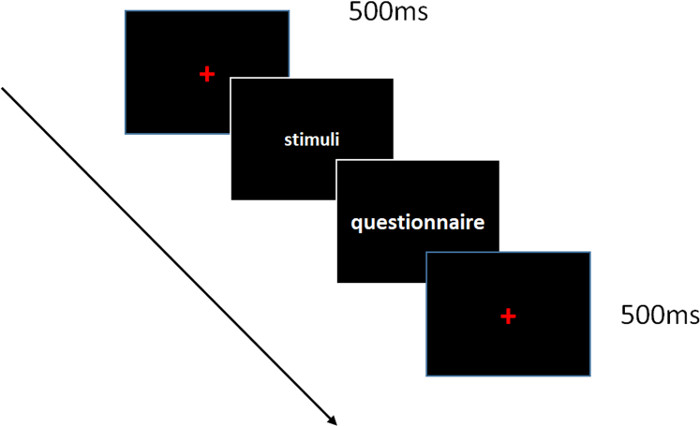

- Start the main experiment and tell the participant that he/she will see a red "+" sign in the middle of the screen, which lasts 500 ms, alerting to the start of the experiment.

- Ask participant to watch the first video while eye tracking is on.

- After the first video, ask participant to complete a questionnaire page, which automatically pops up. Have participants complete a battery of evaluative measures on satisfaction with the viewing by clicking the left mouse button and choosing ratings.

- Ask participant to take a break if desired or continue to another video (see Figure 3, credited to computers in Human Behaviors (CHB) for a flowchart of the experiment).

- Repeat the procedure seven more times for each participant to complete the entire protocol and the eight ads for each.

- Thank, debrief, and pay participant CN¥10.

Figure 3: Experimental flowchart Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Eye-tracking data and self-reported data analysis

NOTE: The eye tracker recorded the whole length of the experiment, including the segments of ad watching and questionnaire responding. In this recording, eye movement data were superimposed over video. Two measures were used in this study, including fixations and durations. A fixation is where the eyes were relatively still, with the central foveal vision being held in place so the human visual system could process the information in that point. A fixation in an eye-tracker was typically defined as a succession of raw gaze points where the velocity was below a pre-defined threshold in the tracker’s gaze filter. More than 60 ms of gaze would be considered as a fixation. Duration, on the other hand, was the length of time between the onset of first gaze point and the last gaze point that make up a fixation.- Slice the entire recording into eight segments corresponding to each ad watching segment. Each clip still contains the original ad and eye movement data.

- On the sliced video, use the tracker software to draw an area of interest (AOI) to distinguish between eye movement data in the barrage area and non-barrage area. The top third was the AOI for barrage, and the lower two-thirds were the AOI for non-barrage.

- First count the number of fixations for each video segment, and separate them into fixations on the barrage AOI and non-barrage AOI.

- Calculate durations.

- Compare duration and the number of fixations at the barrage AOI relative to the whole scene. These two measures allow researchers to infer where participants are focusing and what elements they are paying attention to while watching the videos.

- Analyze self-reported data to examine participants' satisfaction towards video

Representative Results

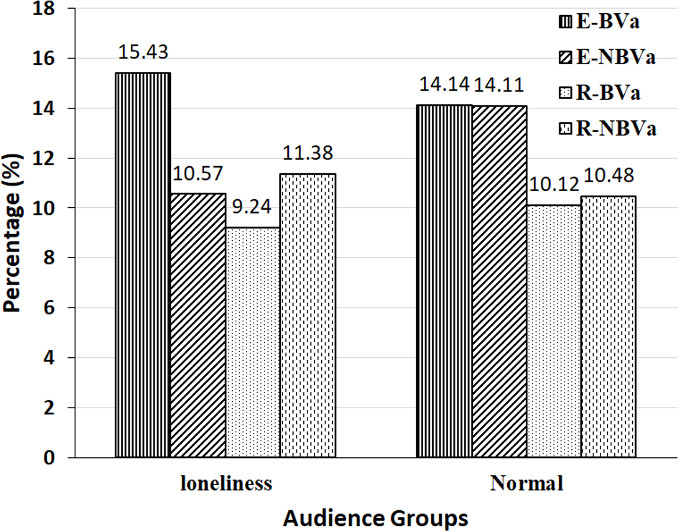

Repeated measures MANOVAs were conducted using duration and fixation as dependent variables, which indicated attention. Results confirmed proposed hypotheses that lonely participants’ gaze stayed on barrage longer than on non-barrage areas when the emotional ads were present. However, when the rational ads were viewed, there was no difference. Such data pattern did not replicate for the low loneliness participants, whose attention remained statistically non-significant when watching emotional ads and rational ads. That is, there was no difference between the gaze probability to the barrage area of interest and the gaze probability of the non-barrage area of interest. The patterns of eye movement data were only in line with the expectations of AMSM. Both duration and fixation count produced significant statistical results59. See Figure 4, credited to CHB, below for the representative fixation count results.

Figure 4: Percentage of fixation count in the barrage Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

For the significant interaction of loneliness, ad appeal, and barrage, pairwise comparisons were computed. The results showed that lonely subjects gazed at the emotional/barrage area the most, whereas a normal audience exhibited no gaze differences within either emotional or barrage condition.

Self-reported data and analyses

The participants’ satisfaction level was measured by using established satisfaction items from previous research63,64. Satisfaction with watched videos largely replicated the duration and fixation results, and as proposed by AMSM, and as shown in Table 1, credited to CHB59. Results showed that a lonely audience was more satisfied watching emotional ads than rational ads, and with barrage than non-barrage, whereas for a normal audience, there were no statistical differences for both interactions.

| Evaluation results of advertising videos (M ± SD) | ||||

| Story-base ads | Hard-selling ads | |||

| Audience type | Barrage video | Non-barrage video | Barrage video | Non-barrage video |

| Loneliness | 4.84±0.69 | 4.45±0.73 | 4.30±0.87 | 4.30±1.06 |

| Normal | 4.75±0.67 | 4.62±0.80 | 4.14±0.79 | 4.21±0.87 |

| Note: revised from Chen & Zhou (2019) published in CHB | ||||

Table 1: Evaluation results of advertising videos

Video 1: Sample barrage ad Please click here to download this video.

Discussion

In this study, eye tracking technology and self-reports are combined to test the validity of the proposed AMSM model. Previous studies mainly used self-reports to explore the relationship between loneliness and media use at the mercy of participants’ ability to articulate. These offline methods fail to understand the psychological processes while watching barrage videos. In this study, eye tracking technology was used to record duration and fixation so researchers could reliably infer how much cognitive resources the participants invested in different video content. The technology is noninvasive, so participants watched the videos without interruption. Results supported the proposed AMSM.

Specifically, this study provided evidence that lonely people gravitated toward emotional content. When emotional content was watched and being discussed (i.e., with barrage), it was more attention getting as measured in gaze duration and fixation counts. In contract, data did not show such effects on people who were not lonely. Equally important, satisfaction evaluation after exposure showed that lonely people were more satisfied with emotional, barrage video, whereas no such conclusion could be drawn for people low in loneliness.

Theoretically, data from this study did not support traditional models of media consumption, claiming either that people used media for the sake of compensating emotional needs, according to the deficiency model, or viewers consumed for broader, more general purposes such as learning and diversion, according to the general use model. Instead, data supported the proposed AMSM model, which posited that emotional content activated viewers’ affective needs, encouraging them to seek out interactive features such as barrage in media to fulfill such needs.

Methodologically, even though eye tracking has been used in communication in a variety of areas such as news consumption and advertising effectiveness, most of these studies explore physical attributes of media such as story placement, layout designs, and product features to explore attention-getting attributes. This study used eye-tracking creatively in the area of affect, by measuring personality variables related to loneliness, and manipulating media variables of emotional content and interactive barrage. It is the researchers’ belief that eye tracking did not have to focus on the obvious, it can also be used to investigate psychological processes. The new barrage format also offers a new and interesting arena for research.

However, this study also has some limitations. For the sake of manipulation convenience, ads were used instead of the usual entertainment content for barrage. Normally, barrage viewers were highly involved in story plots to engage in barrage viewing and participation. Viewing a number of ads seemed artificial. Also, because barrage was pre-produced before the experiment, participants of this study did not have a chance to really engage in barrage activities. As such, the activation process as proposed in AMSA was not specifically investigated. Future research may want to focus on the before and after emotional states to infer whether activation occurs. Also in this study, barrage appeared in the top part of the screen and its crawling direction was predetermined to be from left to right. In real life, barrage texts appear in different styles. Future research may need to allow natural barrage activity to increase external validity.

In sum, the combination of this approach—objective eye tracking data and subjective self-reporting data—allows the researchers to not only untangle the viewing mechanism of lonely on barrage videos, but also to identify the underlying mechanisms of attention allocation. Our hope is that it can serves as a starting point for more such studies.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China for the project (19ZDA332) entitled “Deep Convergence of Media and Innovation Model of Social Governance in the New Era;” a PhD Start-up Fund of the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2017A030310536); and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (19JNQM04). The authors would like to thank Dean/Professor Zhi Tingrong for support and investment in the eye tracking laboratory.

References

- Obersteiner, A., Tumpek, C. Measuring fraction comparison strategies with eye-tracking. ZDM. 48 (3), 255-266 (2016).

- Rauthmann, J. F., Seubert, C. T., Sachse, P., Furtner, M. R. Eyes as windows to the soul: Gazing behavior is related to personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 46 (2), 147-156 (2012).

- Feng, Z. . Eye-movement Based Human-Computer Interaction. , 45-58 (2010).

- Miles, W. The peep-hole method for observing eye movements in reading. The Journal of General Psychology. 1 (2), 373-374 (1928).

- Shi, J., Xu, J. Research progress on eye tracking technology. Optical Instruments. 41 (3), 87-94 (2019).

- Larsson, L., Nystrorm, M., Andersson, R., Stridh, M. Detection of fixations and smooth pursuit movements in high-speed eye-tracking data. Biomedical Signal Processing & Control. 18, 145-152 (2015).

- Yarbus, A. L. . Eye movement and vision. , (1967).

- Holmqvist, K., et al. . Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. , (2011).

- Schindler, M., Lilienthal, A. J. Domain-specific interpretation of eye tracking data: towards a refined use of the eye-mind hypothesis for the field of geometry. Educational Studies in Mathematics. 101 (1), 123-139 (2019).

- . Eye movements: Summing up adjacent angles Available from: https://youtu.be/tNVeYXR-pWI (2019)

- König, P., et al. Eye movements as a window to cognitive processes. Journal of Eye Movement Research. 9 (5), 1-16 (2016).

- Lynch, E. J., Andiola, L. M. If Eyes are the Window to Our Soul, What Role does Eye-Tracking Play in Accounting Research. Behavioral Research in Accounting. 31 (2), 107-133 (2019).

- Su, M. C., et al. An Eye-Tracking System based on Inner Corner-Pupil Center Vector and Deep Neural Network. Sensors. 20 (1), 25 (2019).

- Kassner, M., Patera, W., Bulling, A. Pupil: an open source platform for pervasive eye tracking and mobile gaze-based interaction. Proceedings of the 2014 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing: Adjunct publication. , 1151-1160 (2014).

- Van Slooten, J. C., Jahfari, S., Theeuwes, J. Spontaneous eye blink rate predicts individual differences in exploration and exploitation during reinforcement learning. Scientific Reports. 9 (1), 1-13 (2019).

- Ehinger, B. V., Gross, K., Ibs, I., Koenig, P. A new comprehensive eye-tracking test battery concurrently evaluating the Pupil Labs glasses and the EyeLink 1000. PeerJ. 7, 7086 (2019).

- Plöchl, M., Ossandón, J. P., König, P. Combining EEG and eye tracking: identification, characterization, and correction of eye movement artifacts in electroencephalographic data. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6, (2012).

- Osaki, M. H., et al. Analysis of blink activity and anomalous eyelid movements in patients with hemifacial spasm. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 258 (3), 669-674 (2019).

- Halliwell, E., Dittmar, H. Does size matter? the impact of model’s body size on women’s body-focused anxiety and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 23 (1), 104-122 (2005).

- Guitart, I. A., Guillaume, H., Diogo, H. Using eye-tracking to understand the impact of multitasking on memory for banner ads: the role of attention to the ad. International Journal of Advertising. 38, 1-17 (2018).

- Rieger, D., Bartz, F., Bente, G. Reintegrating the ad: effects of context congruency banner advertising in hybrid media. Journal of Media Psychology Theories Methods & Applications. 1, 1-14 (2015).

- Yang, Q., Wei, S. The Impact of Anthropomorphic Product Ads on Individual Attitude: Evidence from Eye Movements. Journal of Dalian University of Technology (Social Sciences). 40 (03), 49-55 (2019).

- Boerman, S. C., van Reijmersdal, E. A., Neijens, P. C. Using Eye Tracking to Understand the Effects of Brand Placement Disclosure Types in Television Programs. Journal of Advertising. 44 (3), 196-207 (2015).

- Lee, J. W., Ahn, J. Attention to Banner Ads and Their Effectiveness: An Eye-Tracking Approach. International Journal of Electronic Commerce. 17 (1), 119-137 (2012).

- Dutra, L. M., Nonnemaker, J., Guillory, J., Bradfield, B., Kim, A. Smokers’ Attention to Point-of-Sale Antismoking Ads: An Eye-tracking Study. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 4 (1), 631-643 (2018).

- Pfiffelmann, J., Dens, N., Soulez, S. Personalized advertisements with integration of names and photographs: An eye-tracking experiment. Journal of Business Research. 111, 196-207 (2019).

- Strandvall, T. Eye tracking in human-computer interaction and usability research. IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. , 936-937 (2009).

- Larradet, F., Barresi, G., Mattos, L. S. Effects of galvanic skin response feedback on user experience in gaze-controlled gaming: a pilot study. 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). , 2458-2461 (2017).

- Arabadzhiyska, E., Tursun, O. T., Myszkowski, K., Seidel, H. P., Didyk, P. Saccade landing position prediction for gaze-contingent rendering. ACM Transactions on Graphics. 36 (4), 1-12 (2017).

- Chadalavada, R. T., Andreasson, H., Schindler, M., Palm, R., Lilienthal, A. J. Bi-directional navigation intent communication using spatial augmented reality and eye-tracking glasses for improved safety in human-robot interaction. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 61, 101830 (2020).

- Khan, M. Q., Lee, S. Gaze and Eye Tracking: Techniques and Applications in ADAS. Sensors. 19 (24), 5540 (2019).

- Martin, C., Cegarra, J., Averty, P. Analysis of mental workload during en-route air traffic control task execution based on eye-tracking technique. International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics. , 592-597 (2011).

- Lin, D., et al. Tracking the Eye Movement of Four Years Old Children Learning Chinese Words. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 47 (1), 79-93 (2018).

- Paukner, A., Slonecker, E. M., Murphy, A. M., Wooddell, L. J., Dettmer, A. M. Sex and rank affect how infant rhesus macaques look at faces. Developmental Psychobiology. 60 (2), 187-193 (2017).

- Koch, F. S., et al. Procedural memory in infancy: Evidence from implicit sequence learning in an eye-tracking paradigm. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 191, 104733 (2020).

- Hernik, M., Broesch, T. Infant gaze following depends on communicative signals: An eye-tracking study of 5-to 7-month-olds in Vanuatu. Developmental science. 22 (4), 12779 (2019).

- Pham, C., Rundle-Thiele, S., Parkinson, J., Li, S. Alcohol Warning Label Awareness and Attention: A Multi-method Study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53 (1), 39-45 (2018).

- Khachatryan, H., Rihn, A., Campbell, B., Yue, C., Hall, C., Behe, B. Visual Attention to Eco-Labels Predicts Consumer Preferences for Pollinator Friendly Plants. Sustainability. 9 (10), 17-43 (2017).

- Mou, J., Shin, D. Effects of social popularity and time scarcity on online consumer behaviour regarding smart healthcare products: An eye-tracking approach. Computers in Human Behavior. 78, 74-89 (2018).

- Hurley, R. A., Rice, J. C., Koefelda, J., Congdon, R., Ouzts, A. The Role of Secondary Packaging on Brand Awareness: Analysis of 2 L Carbonated Soft Drinks in Reusable Shells Using Eye Tracking Technology. Technology and Science. 30 (11), 711-722 (2017).

- Varela, P., Antúnez, L., Silva Cadena, R., Giménez, A., Ares, G. Attentional capture and importance of package attributes for consumers’ perceived similarities and differences among products: A case study with breakfast cereal packages. Food Research International. 64, 701-710 (2014).

- Ding, Y., Guo, F., Zhang, X., Qu, Q., Liu, W. Using event related potentials to identify a user’s behavioral intention aroused by product form design. Applied Ergonomics. 55, 117-123 (2016).

- Miao, L. Eye-tracking virtual reality system in environmental interaction design. Packaging engineering. 39 (22), 286-293 (2018).

- Yang, Z., Ha, H. . Chinese Dictionary of military knowledge. , (1987).

- Hamasaki, M., Takeda, H., Hope, T., Nishimura, T. Network analysis of an emergent massively collaborative creation community: How can people create videos collaboratively without collaboration. Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social. , (2009).

- Ma, Z., Ge, J. Analysis of Japanese Animation’s Overlaid Comment (danmu): A Perspective of Parasocial Interaction. Journal of International Communication. 8, 116-130 (2014).

- Yang, J. . The new relationship of youth subculture and mainstream culture: “The Legend of Qin” will lead to Asian culture as an example. , (2015).

- Guo, L. . Research on the audience of barrage video websites in China. , (2015).

- Wang, Y. Analysis of the initiative of barrage video site audience: Taking AcFun and BiliBili net as examples. Journal News Research. 1, 54-55 (2015).

- Dai, Y. Barrage: Carnival ethical reflection Era. Editorial Friend. 2, 62-64 (2016).

- Jin, W. . Differences in the usage motives of live commenting video, and the impact of usage motives on the degree of participation as well as dependence. , (2015).

- Chen, Y. New Media, Representation and “Post-subculture” A Review and Rethinking on American Studies of Media and Youth Subculture in Recent Years. Journalism & Communication. 4, 114-124 (2014).

- Zhang, J. The integration of individual differentiation and social representation integration in the network era. Tianjin Social Sciences. 5, 80-83 (2013).

- Fang, J., Ge, J., Zhang, J. Deficiency Paradigm or Global-Use Paradigm – A Review on Parasocial Interaction Researches. Journalism & Communication. 03, 68-72 (2006).

- Pieters, R., Warlop, L., Wedel, M. Breaking through the clutter: Benefits of advertisement originality and familiarity for brand attention and memory. Management Science. 48 (6), 765-781 (2002).

- Bogart, L., Tolley, B. S. The search for information in newspaper advertising. Journal of Advertising Research. 28 (2), 9-19 (1970).

- García, C., Ponsoda, V., Estebaranz, H. Scanning ads: Effects of involvement and of position of the illustration in printed advertisements. Advances in Consumer Research. 27 (1), 104-109 (2000).

- Belanche, D., Flavián, C., Pérez-Rueda, A. Understanding interactive online advertising: Congruence and product involvement in highly and lowly arousing, shippable video ads. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 37, 75-88 (2017).

- Chen, G., Zhou, S., Zhi, T. Viewing mechanism of lonely audience: Evidence from an eye movement experiment on barrage video. Computers in Human Behavior. 101, 327-333 (2019).

- Russell, D. W. UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 66 (1), 20 (1996).

- Wang, D. F. The research on the reliability and validity of Russell’s UCLA scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 3 (1), 23-25 (1995).

- Liebermann, Y., Flint-Goor, A. Message strategy by product-class type: A matching model. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 13 (3), 237-249 (1996).

- Lutz, J., Kassarjian, H., Rovertson, T. Role of attitude theory in marketing. Perspective in Consumer Behavior. , 317-339 (1991).

- Ruiz, S., Sicilia, M. The impact of cognitive and/or affective processing styles on consumer response to advertising appeals. Journal of Business Research. 57 (6), 657-664 (2004).