Using Zebrafish Models of Human Influenza A Virus Infections to Screen Antiviral Drugs and Characterize Host Immune Cell Responses

Summary

Systemic and localized zebrafish infection models for human influenza A virus are demonstrated. Using a systemic infection model, zebrafish can be used to screen antiviral drugs. Using a localized infection model, zebrafish can be used to characterize host immune cell responses.

Abstract

Each year, seasonal influenza outbreaks profoundly affect societies worldwide. In spite of global efforts, influenza remains an intractable healthcare burden. The principle strategy to curtail infections is yearly vaccination. In individuals who have contracted influenza, antiviral drugs can mitigate symptoms. There is a clear and unmet need to develop alternative strategies to combat influenza. Several animal models have been created to model host-influenza interactions. Here, protocols for generating zebrafish models for systemic and localized human influenza A virus (IAV) infection are described. Using a systemic IAV infection model, small molecules with potential antiviral activity can be screened. As a proof-of-principle, a protocol that demonstrates the efficacy of the antiviral drug Zanamivir in IAV-infected zebrafish is described. It shows how disease phenotypes can be quantified to score the relative efficacy of potential antivirals in IAV-infected zebrafish. In recent years, there has been increased appreciation for the critical role neutrophils play in the human host response to influenza infection. The zebrafish has proven to be an indispensable model for the study of neutrophil biology, with direct impacts on human medicine. A protocol to generate a localized IAV infection in the Tg(mpx:mCherry) zebrafish line to study neutrophil biology in the context of a localized viral infection is described. Neutrophil recruitment to localized infection sites provides an additional quantifiable phenotype for assessing experimental manipulations that may have therapeutic applications. Both zebrafish protocols described faithfully recapitulate aspects of human IAV infection. The zebrafish model possesses numerous inherent advantages, including high fecundity, optical clarity, amenability to drug screening, and availability of transgenic lines, including those in which immune cells such as neutrophils are labeled with fluorescent proteins. The protocols detailed here exploit these advantages and have the potential to reveal critical insights into host-IAV interactions that may ultimately translate into the clinic.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), influenza viruses infect 5-10% of adults and 20-30% of children annually and cause 3-5 million cases of severe illness and up to 500,000 deaths worldwide1. Yearly vaccinations against influenza remain the best option to prevent disease. Efforts like the WHO Global Action Plan have increased seasonal vaccine use, vaccine production capacity, and research and development into more potent vaccine strategies in order to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with seasonal influenza outbreaks2. Antiviral drugs like neuraminidase inhibitors (e.g. Zanamivir and Oseltamivir) are available in some countries and have proven effective in mitigating symptoms, when administered within the first 48 hr of onset3,4,5. Despite global efforts, containment of seasonal influenza outbreaks remains a formidable challenge at this time, as influenza virus antigenic drift often exceeds current abilities to adapt to the changing genome of the virus6. Vaccine strategies targeting new strains of virus must be developed in advance and are sometimes rendered less than optimally effective due to unforeseen changes in the types of strains that eventually predominate in an influenza season. For these reasons, there is a clear need to develop alternative therapeutic strategies for containing infections and reducing mortalities. By achieving a better understanding of the host-virus interaction, it may be possible to develop new anti-influenza medicines and adjuvant therapies7,8.

The human host-influenza A virus (IAV) interaction is complex. Several animal models of human IAV infection have been developed in order to gain insight into the host-virus interaction, including mice, guinea pigs, cotton rats, hamsters, ferrets, and macaques9. While providing important data that have enhanced the understanding of host-IAV dynamics, each model organism possesses significant drawbacks that must be considered when attempting to translate the findings into human medicine. For example, mice, which are the most widely used model, do not readily develop IAV-induced infection symptoms when infected with human influenza isolates9. This is because mice lack the natural tropism for human influenza isolates since mouse epithelial cells express α-2,3 sialic acid linkages instead of the α-2,6 sialic acid linkages expressed on human epithelial cells10. The hemagglutinin proteins present in human IAV isolates favorably bind and enter host cells bearing α-2,6 sialic acid linkages through receptor-mediated endocytosis9,11,12,13. As a consequence, it is now accepted that in developing mouse models for human influenza, care must be taken to pair the appropriate strain of mouse with the appropriate strain of influenza in order to achieve disease phenotypes that recapitulate aspects of the human illness. In contrast, epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract of ferrets possess α-2,6 sialic acid linkages that resemble human cells14. Infected ferrets share many of the pathological and clinical features observed in the human disease, including the pathogenicity and transmissibility of human and avian influenza viruses14,15. They are also highly amenable to vaccine efficacy trials. Nevertheless, the ferret model for human influenza has several disadvantages principally related to their size and cost of husbandry that make acquisition of statistically significant data challenging. In addition, ferrets have previously displayed differences in drug pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and toxicity that make testing efficacy difficult. For example, ferrets exhibit toxicity to the M2 ion channel inhibitor amantadine16. Thus, it is clear that in choosing an animal model to study questions about human IAV infections, it is important to consider its inherent advantages and limitations, and the aspect of the host-virus interaction that is under investigation.

The zebrafish, Danio rerio, is an animal model that provides unique opportunities for investigating microbial infection, host immune response, and potential drug therapies17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. The presence of α-2,6-linked sialic acids on the surface of cells in the zebrafish suggested its susceptibility to IAV, which was borne out in infection studies and imaged in vivo using a fluorescent reporter strain of IAV19. In IAV-infected zebrafish, increased expression of the antiviral ifnphi1 and mxa transcripts indicated that an innate immune response had been stimulated, and the pathology displayed by IAV-infected zebrafish, including edema and tissue destruction, was similar to that observed in human influenza infections. Furthermore, the IAV antiviral neuraminidase inhibitor Zanamivir limited mortality and reduced viral replication in zebrafish19.

In this report, a protocol for initiating systemic IAV infections in zebrafish embryos is described. Using Zanamivir at clinically relevant doses as a proof-of-principle, the utility of this zebrafish IAV infection model for screening compounds for antiviral activity is demonstrated. In addition, a protocol for generating a localized, epithelial IAV infection in the zebrafish swim bladder, an organ that is considered to be anatomically and functionally analogous to the mammalian lung21,29,30,31, is described. Using this localized IAV infection model, neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection can be tracked, enabling investigations into the role of neutrophil biology in IAV infection and inflammation. These zebrafish models complement existing animal models of human IAV infections and are particularly useful for testing small molecules and immune cell responses because of the possibility of enhanced statistical power, capacity for moderate- to high-throughput assays, and the abilities to track immune cell behavior and function with light-microscopy.

Protocol

All work should be performed using biosafety level 2 (or BSL2) standards described by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and in accordance with directives established by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC). Please confer with the appropriate officials to ensure safety and compliance.

1. Zebrafish Care and Maintenance

- Spawn zebrafish and collect the required number of embryos for the experiments. When necessary, mass breeding tanks, like those described by Adatto et al.32, can be employed to collect large numbers of developmentally-staged embryos.

- Allow embryos to develop until desired developmental stage (48 hr post-fertilization for a systemic IAV infection [section 3] or 5 days post-fertilization for a localized, swim bladder infection [section 4]) in deep Petri dishes at low density (<100 embryos/dish) at 28 °C in sterile egg water containing 60 µg/ml sea salt (e.g., Instant Ocean) in distilled water.

- Remove dead embryos with plastic transfer pipets and change egg water daily to ensure optimal health and development.

2. Preparation of Materials and Reagents

- Prepare a 4 mg/ml stock solution of Tricaine-S (adjust pH to 7.0-7.4) in distilled water and autoclave. Store at 4 °C.

- Pull borosilicate glass capillaries with filaments using a micropipette puller (e.g. Micropipette Puller with the following settings: pressure setting =100, heat = 550, pull = [no value], velocity = 130, time = 110).

NOTE: Prior to trimming the needle, the length from where the needle begins to taper to the tip of the needle would be approximately 12-15 mm. This can vary, however, based on preference and application. A longer, more gradual taper may be more preferable because of the increased ability to pierce the embryo and the reduced risk of the needle bending or breaking. - Melt 2 g of agarose in 100 ml egg water using a microwave. Make plates on which to line up and inject the embryos by pouring melted agarose into deep Petri dishes and allowing it to solidify.

- Make a 10 mg/ml stock of Zanamivir in nuclease-free water. Aliquot and freeze at -20 °C.

- Melt 0.5 g agarose in 50 ml egg water using a microwave to make embryo mounting agarose. Maintain in water bath at 50 °C until ready to use during imaging.

3. Systemic IAV Infection (48 hr post-fertilization)

CAUTION: All research personnel should consult with their supervisors and physicians regarding vaccination prior to starting work with IAV.

- Manually dechorionate embryos on the day of the experiment using #5 forceps. Take care to remove and euthanize embryos that have been injured in the process in 200 µg/ml Tricaine solution.

- Preparation of IAV for Microinjection

NOTE: Strains that have been shown to infect zebrafish embryos are influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (APR8), influenza A X-31 A/Aichi/68 (H3N2) (X-31), and the fluorescent reporter influenza strain NS1-GFP33. Details about APR8 and X-31, and other strains, can be found at the Influenza Research Database- Propagate the NS1-GFP strain of IAV in embryonated chicken eggs as previously described34,35. Collect, aliquot, and titer the allantoic fluid containing IAV, and store at -80 °C. Pre-titered APR8 and X-31 viruses can be purchased commercially.

- Just prior to infection, rapidly thaw an IAV aliquot in gloved hands and then quickly place on ice to reduce loss of titer.

- Viral dilution

- If using the APR8 or X-31 viruses, dilute to 3.3 x 106 egg infective dose 50% (EID50)/ml in sterile, ice-cold PBS supplemented with 0.25% phenol red (to aid in visualization) in a laminar flow hood. Simultaneously set up a control containing sterile PBS with 0.25% phenol red.

- If using NS1-GFP strain33, dilute to ~1.5 x 102 plaque forming units (PFU) per nl in sterile, ice-cold PBS containing 0.25% phenol red (to aid in visualization) in a laminar flow hood. Simultaneously set up a control containing allantoic fluid from uninfected chicken eggs diluted like the virus in sterile PBS with 0.25% phenol red.

- Maintain IAV on ice until ready to use.

- Pipet virus solution into microinjection needles using microloader tips just prior to use. Insert microinjection needle into the appropriate holder of the injection apparatus (e.g. MPPI-3 pressure injection system).

- While viewing under the stereo microscope, gently clip the microinjection needle tip with sharp, sterilized #5 forceps.

NOTE: It is recommended that the microinjection tip be clipped gradually. - Depress the foot pedal of the pressure injection system and inject into a drop of microscope immersion oil on a calibration micrometer slide. Measure the diameter of the drop. Calculate the volume of the drop using the equation, V=4/3πr3, where V is volume in nl and r is the radius in µm.

NOTE: If the drop diameter is too small, additional glass may be clipped or pressure and timing settings can be adjusted. If the drop diameter is too large, pressure and timing settings can be adjusted. - Adjust pressure and timing settings on the pressure injector and/or reclip the needle tip until the desired injection volume is achieved (typically 1-3 nl). Pressure settings between 20 and 30 psi and pulse duration settings between 40 and 80 msec are typical. Adjust back pressure so that it counters capillary pressure but does not leak IAV (net zero pressure).

- Propagate the NS1-GFP strain of IAV in embryonated chicken eggs as previously described34,35. Collect, aliquot, and titer the allantoic fluid containing IAV, and store at -80 °C. Pre-titered APR8 and X-31 viruses can be purchased commercially.

- Align Embryos for Injection

- Anesthetize dechorionated embryos in 200 µg/ml Tricaine.

- Once movement ceases, transfer 10-20 embryos to a 2% agarose plate (prepared in section 2.3) with a plastic pipette. Use plastic pipette to remove excess liquid.

- Gently align embryos for microinjection with a fire-polished and sealed borosilicate glass capillary. Using a stereo microscope, gently orient embryos so that the duct of Cuvier or the posterior cardinal vein is in line with the microinjection needle (Figure 1A).

- IAV Microinjection

- Gently insert the microinjection needle into the duct of Cuvier or the posterior cardinal vein. Depress foot pedal to inject the desired volume of IAV into the circulatory system of the embryo (Figure 1A). Embryos can be injected more than one time if necessary.

NOTE: The injection bolus should be swept up into the circulation and distributed throughout the body. If injection volume collects at the site of injection, remove embryo from experiment and euthanize. - Repeat injections on different embryos with control solution specific to the strain of virus chosen. For APR8 and X-31, use the control described in section 3.2.2.1; for the NS1-GFP, use the control described in section 3.2.2.2.

- Gently insert the microinjection needle into the duct of Cuvier or the posterior cardinal vein. Depress foot pedal to inject the desired volume of IAV into the circulatory system of the embryo (Figure 1A). Embryos can be injected more than one time if necessary.

- Transfer embryos to labeled Petri dishes containing sterile egg water and place in incubators at 33 °C.

NOTE: Infected embryos should be grown at 33 °C to support enhanced viral replication. In addition, incubation at 33 °C more closely mimics the temperature of the human upper respiratory tract, which is in close contact with lower temperatures in the external environment and is where IAV infections occur. Embryos can acclimate to a broad temperature range34.

4. Localized, Swim Bladder IAV Infection in Tg(mpx:mCherry) Transgenic Zebrafish (5 days post-fertilization)

- Preparation of IAV for Microinjection

- Dilute the NS1-GFP strain and control injection solution as described in section 3.2.

- Prepare needles as described in section 2.2.

- Align Tg(mpx:mCherry)35 larvae containing inflated swim bladders as described in section 3.3 with the following exception. Align larvae in such a way that the needle can pierce the swim bladder and the virus can be deposited into the posterior of the swim bladder, as previously described36 (Figure 2A).

- IAV Microinjection

- Gently insert the microinjection needle into the swim bladder and inject the desired volume (e.g. 5 nl) towards the posterior of the structure (Figure 2A).

NOTE: The injection bolus should collect toward the posterior and the swim bladder's air bubble should be displaced forward. GFP expression should begin to be observed at 3 hr post-injection. - Repeat injections with control solution specific to the strain of virus chosen, as described in section 3.4.2.

- Gently insert the microinjection needle into the swim bladder and inject the desired volume (e.g. 5 nl) towards the posterior of the structure (Figure 2A).

- Transfer larvae to Petri dishes containing sterile egg water and place in incubators at 33 °C.

5. Antiviral Drug Treatment

NOTE: The protocol below describes the Zanamivir treatment previously shown in Gabor et al.19. This protocol can be modified to screen other antiviral drugs and has the potential to be modified to screen multiple compounds in a 96 well plate, high-throughput format.

- At 3 hr post infection, replace egg water of NS1-GFP- and control-infected fish with sterile egg water containing 0, 16.7, or 33.3 ng/ml Zanamivir.

NOTE: These concentrations were chosen in order to attempt to replicate the physiological levels achieved following administration of Zanamivir in human patients (100, 200, or 600 mg, i.v., twice daily or 10 mg inhaled, twice daily). The serum concentrations in human patients ranged from 9.83 to 45.3 ng/ml36. - Over the course of 5 days, change egg water every 12 hr and replace with sterile egg water containing the appropriate amount of Zanamivir.

- Track Course of Infection.

- Anesthetize zebrafish in 200 µg/ml Tricaine. Monitor GFP expression by stereo fluorescence microscopy to visually observe differences in infection patterns between IAV-infected and control fish and among the fish immersed in the different concentrations of drugs.

- Track morbidity and mortality over the course of 5 days.

- Record observations about infection dynamics related to disease pathology, including signs of lethargy and evidence of edema, differences in pigmentation, ocular and craniofacial deformities, and lordosis. Disease pathology typically becomes apparent in control infected fish at 24-48 hr post-injection, depending on the amount of virus injected. Collect images 24 hr post-injection.

- Every 24 hr for 5 days post-infection, record the number of dead, morbid, and healthy larvae. Death is defined by the absence of a discernible heartbeat. Plot data as desired. For example, plot data as a stacked bar graph, with percentages of healthy, morbid, or dead fish plotted on the y-axis and the treatment group on the x-axis.19

NOTE: Mortalities may be scored by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. Depending on application, it may be appropriate to develop alternative approaches for scoring fish morbidity, including a scoring matrix that may quantify the degrees of morbidity based on the aforementioned pathological features observed. - Consult with a statistician to apply the appropriate statistical analyses.

6. Neutrophil Migration

NOTE: The protocol below describes a method for tracking neutrophil migration to the swim bladder following a localized, epithelial IAV infection. The methods described can be modified to test the effects of genetic and chemical manipulations. Using this technique, it will be possible to characterize the mechanisms underlying neutrophil behavior during an IAV infection.

- Mounting Zebrafish for Imaging

- Anesthetize larvae to be imaged in 200 µg/ml Tricaine.

- Transfer an individual Tg(mpx:mCherry) larva that has been infected with NS1-GFP to a well of a 24 well, glass bottom plate in a small droplet of egg water (~50-100 µl). Repeat with other IAV-infected and control fish.

- Slowly add 1% agarose embryo mounting media to each well (section 2.5), taking care not to introduce large bubbles.

- Gently adjust the position of the larva so that it is mounted on its side. Goody and Henry37 describe how to make probes that function well in this application using insect pins that are mounted in borosilicate glass capillaries with filaments and superglued in place.

- Once the agarose hardens, gently fill the individual wells with egg water containing 200 µg/ml Tricaine.

- With a confocal microscope, capture a z stack series of brightfield and fluorescence images using a 20X objective focused on the swim bladder.

- Set the upper and lower limits so that they capture all visibly observable green and red fluorescence.

- Capture images at 2.0 µsec/pixel with steps that are ≤ 4 µm. Increasing time per pixel and reducing distance between steps (e.g. 0.5 – 1.0 µm) increases picture resolution and quality.

- Generate a two-dimensional image by merging layers.

- Compare the number of mpx-mCherry-positive neutrophils present in the swim bladders of IAV-infected and control-injected zebrafish.

Representative Results

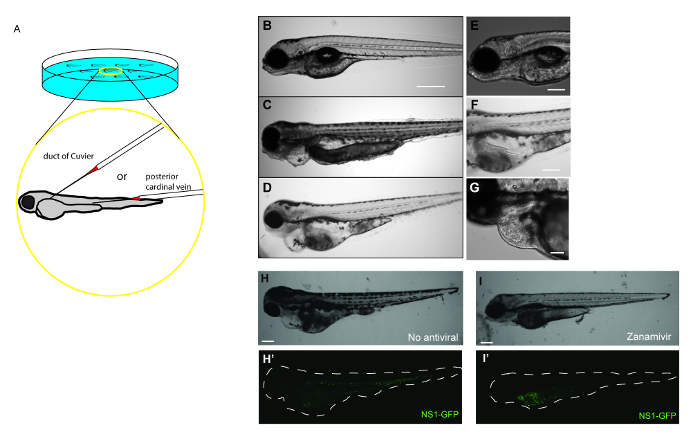

Here, data showing how systemic IAV infection in zebrafish can be used to test drug efficacy (Figure 1A) are provided. Embryos at 48 hr post-fertilization are injected with APR8 (Figures 1C, 1F), X-31 (Figures 1D, 1G), or NS1-GFP (Figures 1H-1I) via the duct of Cuvier to initiate a viral infection. Another cohort of embryos at 48 hr post-fertilization were injected to serve as controls for viral infection (Figures 1B, 1E). By 48 hr post-infection, zebrafish injected with IAV exhibited evidence of pericardial edema (Figures 1C, 1D) and circulatory arrest (Figure 1F), with erythrocytes present throughout the pericardium (Figure 1G). Using NS1-GFP, the initial expression of GFP by fluorescence microscopy as early as 3 hr post-infection was observed. At that point, zebrafish were exposed to a 33.3 ng/ml dose of the neuraminidase inhibitor Zanamivir. This dose is roughly equivalent to the 200 mg dose given to human patients. Control infected fish not exposed to Zanamivir (Figures 1H, 1H') exhibited features of edema and systemic GFP expression. Reduced gross pathology and GFP fluorescence (Figures 1I, 1I') in NS1-GFP-infected larvae exposed to Zanamivir were observed. The reduction in GFP was most noticeable in the bodies of larvae, while very little change was observed in the yolk sacs. Fish treated with Zanamivir exhibited less morbidity, as evidenced by improved swimming motility and reduced levels of edema in the heart, and improved survival. These findings complement a more comprehensive study19 and show the value of this model for drug screening.

A localized zebrafish swim bladder infection model31 has been adapted for IAV infection. NS1-GFP virus was injected into the swim bladders of 5 d post-fertilization Tg(mpx:mCherry) larvae to initiate a localized, epithelial infection (Figure 2A). PBS was injected into the swim bladder as a control to demonstrate the specificity of neutrophil recruitment toward IAV-infected cells. The recruitment of mCherry-labeled neutrophils into the swim bladder was tracked. At 20 hr post-infection, considerable migration of neutrophils into the swim bladders of IAV-infected fish relative to PBS-injected controls (Figures 2B, 2B', 2C, 2C') was observed. These data demonstrate that IAV can recruit neutrophils to the swim bladder, just as it recruits neutrophils to the human lung.

Figure 1: Antiviral drug treatment mitigates the severity of IAV infection in zebrafish. (A) Schematic demonstrating possible IAV injection sites to initiate systemic infections in a 48 hr post-fertilization embryo. Embryos can be injected at multiple sites in the vasculature to initiate a systemic infection, including the duct of Cuvier and the posterior cardinal vein just above the yolk extension. (B–I) Gross pathology and GFP fluorescence of zebrafish embryos injected into the duct of Cuvier with IAV. (B-G) Fish infected with IAV and examined at 48 hr post-infection for signs of viral infection and disease. (B–D) Single focal planes of control or IAV-infected fish were collected (side-mounted, anterior left, dorsal top, 4X magnification, scale bar = 500 µm). (B) Control fish were injected with PBS and display normal morphology. (C–D) Embryos infected with APR8 (C) or X-31 (D) commonly exhibited pericardial edema (filled arrow). Embryos also had necrotic tissue, evident in (C). (E) Control fish were injected with PBS and display no evidence of pathology (scale bar = 250 µm). (F) Embryos infected with APR8 displays circulatory arrest (notched arrowhead, scale bar = 250 µm). (G) Embryo injected with X-31 influenza displays both pericardial edema (arrow) and pooled erythrocytes throughout the pericardium (notched arrowhead, scale bar = 100 µm). (H,I) Representative images showing effects of an antiviral drug on IAV-infected zebrafish (scale bar = 200 µm). (H) Brightfield and (H') fluorescence image showing an embryo injected with NS1-GFP (no antiviral drug treatment). Notice edema and GFP expression especially in the common cardinal vein region. (I, I') Treatment with an antiviral drug reduced the infection, as evidenced by reduced pathology, including diminished edema, and diminished GFP expression within the white dashed outline of the body, particularly in the vasculature, which is indicative of reduced viral burden. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Neutrophils are recruited to sites of localized IAV infection. (A) Schematic demonstrating the injection approach needed to initiate a localized IAV infection in an inflated zebrafish swim bladder at 5 d post-fertilization. (B, C) Neutrophil recruitment to the swim bladder following NS1-GFP infection. Z-stack images (4 µm steps) were collected by confocal microscopy (20X magnification). Images were flattened into two-dimensions (side-mounted, anterior left, dorsal top). Tg(mpx:mCherry) zebrafish (5 d post-fertilization) were injected with (B,B') allantoic fluid diluted with PBS and 0.25% phenol red or (C,C') NS1-GFP (7.2 × 102 PFU/embryo) diluted in allantoic fluid and PBS with 0.25% phenol red. At 16 hr post-infection, neutrophils were present in an IAV-infected swim bladder (C, C': green fluorescence shows localized infection; C': red cells are neutrophils, white arrow identifies representative neutrophil). (B, B') No evidence of GFP expression indicative of IAV infection and no recruitment of neutrophils to the swim bladder was observed in the larvae injected with the allantoic fluid in PBS. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

To maximize the benefits gained from using a small animal to model human host-pathogen interactions, it is important to frame research questions and test hypotheses that capitalize on the inherent advantages of the model system. As a model for human IAV infection, the zebrafish has several strengths, including high fecundity, optical clarity, amenability to drug screening, and availability of transgenic lines that label immune cells like neutrophils. The zebrafish has been developed as an increasingly powerful alternative to the mouse model system for the study of inflammation and innate immunity. Because they lack a functioning adaptive immune response during the first 4-6 weeks of development, zebrafish mount innate immune responses to protect against injury and infection37. During this early period in development, it is possible to isolate and study mechanisms of the antiviral response arising from the innate immune response alone. This work has been facilitated by the development of transgenic zebrafish lines like Tg(mpx:mCherry), which labels neutrophils with a red fluorescent protein.

Zebrafish models for IAV infection that resemble human disease were recently described19. It was demonstrated that zebrafish possess α-2,6-linked sialic acid residues on their cells that provide IAV viruses the tropism to bind, attach, and enter cells. In this manuscript and in Gabor et al.19, it has been shown that two different strains of IAV (A/PR/8/34 [H1N1] and X-31 A/Aichi/68 [H3N2]), as well as the recombinant NS1-GFP strain that results in GFP translation in infected cells, could infect, replicate, and cause mortality when injected into the circulatory system of larval zebrafish. Injection of the virus is critical to this infection method, as exposure to IAV via immersion does not work reliably. Infected fish should be transferred to a 33 °C incubator to ensure viral replication. It is important to note that the human respiratory tract, where influenza infections occur, is typically 33 °C. Incubation at 28 °C, which is more typical temperature for zebrafish incubation, fails to produce a reliable infection. Further, it is essential to test each lot received from the manufacturer or batch of IAV produced prior to use in an experiment due to variability that affects infectivity and disease progression in the zebrafish. When the infective dose is titrated correctly, the vast majority of zebrafish infected with these strains of IAV should exhibit gross disease phenotypes typified by edema, as early as 24 hr post-infection, that progressively worsen, craniofacial abnormalities by 48 hr post-infection, lordosis by 72 hr post-infection, and approximately 50% should succumb to the infection by 5 d post-infection. Histopathology at 48 hr post-infection should include evidence of gill, head kidney, and liver necrosis, as well as indications of fluid in the pericardium. In establishing these findings as the predictable outcome of an IAV infection in zebrafish, it is possible to screen candidate anti-influenza drug compound candidates. With this in mind, a proof-of-principle protocol for screening an antiviral drug based on original findings described in Gabor et al.19 are demonstrated. Using the neuraminidase inhibitor Zanamivir, at a dose that is predicted to mimic levels observed in human blood, delayed onset of morbidity and reduced mortality through an apparent effect on viral replication/spread, as determined by NS1-GFP fluorescence, was observed. The zebrafish IAV model is ideally suited for moderate- to high-throughput small molecule screens. Because infections can only occur only through manual injection into the circulation via the duct of Cuvier or posterior cardinal vein, the size of the screens are limited by the number of technicians establishing the infections and their proficiencies in performing the technique. Nevertheless, it is possible to inject at least 200 zebrafish embryos per technician per hour. While successful in demonstrating antiviral activity for Zanamivir in a zebrafish infection model, it must be acknowledged that drug screening in all animal models, including zebrafish, must be carefully controlled38. The way a drug is absorbed and metabolized differs from animal-to-animal, and is difficult to predict. Nevertheless, as a method for screening new anti-influenza drugs, this zebrafish IAV infection model presents an exciting opportunity to survey many thousands of small molecules in an animal with organs orthologous to humans and with highly-conserved integrative physiology.

In addition to being a model for systemic infection, the zebrafish can also serve as a model for localized infection when IAV is injected into the swim bladder19, the functional analogue of the human lung21,29,30,31. When properly titrated, zebrafish that are infected with the NS1-GFP strain at 5 d post-fertilization should exhibit evidence of punctate fluorescence around the epithelia of the swim bladder by 1 d post-infection. Using this localized infection strategy, neutrophil behavior in response to the infection can be tracked. Like human neutrophils, zebrafish neutrophils are a principal cellular mediator in innate immunity, functioning during acute responses to tissue injury and infection and playing critical roles during chronic inflammation24. There is a growing recognition that neutrophils play a crucial role in the immune response to influenza infection. Indeed, it has become apparent that neutrophils function as "double-edged swords" in mediating the immune response. While essential to the antiviral response necessary to control influenza infections, neutrophils also contribute to an excessively inflammatory environment in the lung that can damage host tissues and increase the risk of mortality39,40,41,42,43. There is considerable conservation of gene synteny between the zebrafish and human genomes, and with this orthology, there is also significant functional conservation in neutrophil biology. Zebrafish neutrophils bear many similarities to human neutrophils, including a polymorphic nucleus, the presence of primary and secondary granules, and functional myeloperoxidase and NADPH oxidase22. In addition, zebrafish neutrophils can engulf bacteria and release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)44. Several transgenic zebrafish lines have been developed to help identify and dissect the functions of neutrophil biology27,45,46,47. This infection protocol is flexible and can be modified to test multiple neutrophil functions using these alternative tools. This localized zebrafish IAV infection model enables questions related to the host immune response to be addressed, and in particular those mediated by neutrophils.

Studies carried out in mammalian model species have yielded valuable information40,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, but few real-time experiments involving IAV infection have been performed, limiting the understanding of the complex interplay among the components of the vertebrate innate immune response in the host. Over the last decade, the use of the zebrafish animal model system has yielded a watershed of information regarding host-pathogen interactions21,47,56,57, and has also offered important information as a tool for drug discovery. A combination of molecular techniques and imaging microscopy have allowed a better understanding of innate immune responses and how these are manifested in vivo 17,18,27. The discovery that zebrafish can be infected with IAV19, and that the zebrafish shares important immunological similarities with mammalian systems, including human, has opened the door to the study of an important human viral pathogen. The protocols described are adaptable to other applications and have the potential to yield critical discoveries regarding host-virus interactions that may have profound clinical impacts on human health.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mark Nilan for zebrafish care and maintenance and Meghan Breitbach and Deborah Bouchard for propagating NS1-GFP and determining IAV titers. This research was supported by NIGMS grant NIH P20GM103534 and the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station (Publication Number 3493).

Materials

| Instant Ocean | Spectrum Brands | SS15-10 | |

| 100 x 25 mm sterile disposable Petri dishes | VWR | 89107-632 | |

| Transfer pipettes | Fisherbrand | 13-711-7M | |

| Tricaine- S (MS-222) | Western Chemical | ||

| Borosilicate glass capillary with filament | Sutter Instrument | BF120-69-10 | |

| Flaming/Brown micropipette puller | Sutter Instrument | P-97 | |

| Agarose | Lonza | 50004 | |

| Zanamivir | AK Scientific | G939 | |

| Dumont #5 forceps | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 72700-D | |

| Microloader tips | Eppendorf | 930001007 | |

| Microscope immersion oil | Olympus | IMMOIL-F30CC | |

| Microscope stage calibration slide | AmScope | MR095 | |

| MPPI-3 pressure injector | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | ||

| Stereo microscope | Olympus | SZ61 | |

| Back pressure unit | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | BPU | |

| Micropipette holder kit | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | MPIP | |

| Foot switch | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | FSW | |

| Micromanipulator | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | MM33 | |

| Magnetic base | Applied Scientific Instrumentation | Magnetic Base | |

| Phenol red | Sigma-Aldrich | P-4758 | |

| Low temperature incubator | VWR | 2020 | |

| SteREO Discovery.V12 | Zeiss | ||

| Illuminator | Zeiss | HXP 200C | |

| Cold light source | Zeiss | CL6000 LED | |

| Glass-bottom multiwell plate, 24 well | Mattek | P24G-0-13-F | |

| Confocal microscope | Olympus | IX-81 with FV-1000 laser scanning confocal system | |

| Fluoview software | Olympus | ||

| Prism v6 | GraphPad | ||

| Influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) virus | Charles River | 490710 | |

| Influenza A X-31, A/Aichi/68 (H3N2) | Charles River | 490715 | |

| Influenza NS1-GFP | Referenced in Manicassamy et al. 2010 | ||

| Tg(mpx:mCherry) | Referenced in Lam et al. 2013 | ||

References

- De Clercq, E. Antiviral agents active against influenza A viruses. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 5 (12), 1015-1025 (2006).

- von Itzstein, M. The war against influenza: discovery and development of sialidase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 6 (12), 967-974 (2007).

- Fiore, A. E., et al. Antiviral Agents for the Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis of Influenza. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. , 1-26 (2011).

- Krammer, F., Palese, P. Advances in the development of influenza virus vaccines. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 14 (3), 167-182 (2015).

- Ren, H., Zhou, P. Epitope-focused vaccine design against influenza A and B viruses. Curr Opin Immunol. 42, 83-90 (2016).

- Webster, R. G., Govorkova, E. A. Continuing challenges in influenza. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1323, 115-139 (2014).

- Bouvier, N. M., Lowen, A. C. Animal Models for Influenza Virus Pathogenesis and Transmission. Viruses. 2 (8), 1530-1563 (2010).

- Ibricevic, A., et al. Influenza virus receptor specificity and cell tropism in mouse and human airway epithelial cells. J Virol. 80 (15), 7469-7480 (2006).

- Skehel, J. J., Wiley, D. C. RECEPTOR BINDING AND MEMBRANE FUSION IN VIRUS ENTRY: The Influenza Hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 69 (1), 531 (2000).

- Rust, M. J., Lakadamyali, M., Zhang, F., Zhuang, X. Assembly of endocytic machinery around individual influenza viruses during viral entry. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11 (6), 567-573 (2004).

- Stencel-Baerenwald, J. E., Reiss, K., Reiter, D. M., Stehle, T., Dermody, T. S. The sweet spot: defining virus-sialic acid interactions. Nature Rev Microbiol. 12 (11), 739-749 (2014).

- Herlocher, M. L., et al. Ferrets as a Transmission Model for Influenza: Sequence Changes in HA1 of Type A (H3N2) Virus. J Infect Dis. 184 (5), 542-546 (2001).

- Belser, J. A., Katz, J. M., Tumpey, T. M. The ferret as a model organism to study influenza A virus infection. Dis Model Mech. 4 (5), 575-579 (2011).

- Cochran, K. W., Maassab, H. F., Tsunoda, A., Berlin, B. S. Studies on the antiviral activity of amantadine hydrochloride. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 130 (1), 432-439 (1965).

- de Oliveira, S., Boudinot, P., Calado, A., Mulero, V. Duox1-derived H2O2 modulates Cxcl8 expression and neutrophil recruitment via JNK/c-JUN/AP-1 signaling and chromatin modifications. J Immunol. 194 (4), 1523-1533 (2015).

- de Oliveira, S., et al. Cxcl8 (IL-8) mediates neutrophil recruitment and behavior in the zebrafish inflammatory response. J Immunol. 190 (8), 4349-4359 (2013).

- Gabor, K. A., et al. Influenza A virus infection in zebrafish recapitulates mammalian infection and sensitivity to anti-influenza drug treatment. Dis Model Mech. 7 (11), 1227-1237 (2014).

- Galani, I. E., Andreakos, E. Neutrophils in viral infections: Current concepts and caveats. J Leukoc Biol. 98 (4), 557-564 (2015).

- Gratacap, R. L., Rawls, J. F., Wheeler, R. T. Mucosal candidiasis elicits NF-kappaB activation, proinflammatory gene expression and localized neutrophilia in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 6 (5), 1260-1270 (2013).

- Henry, K. M., Loynes, C. A., Whyte, M. K., Renshaw, S. A. Zebrafish as a model for the study of neutrophil biology. J Leukoc Biol. 94 (4), 633-642 (2013).

- Mathias, J. R., et al. Live imaging of chronic inflammation caused by mutation of zebrafish Hai1. J Cell Sci. 120 (19), 3372-3383 (2007).

- Shelef, M. A., Tauzin, S., Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophil migration: moving from zebrafish models to human autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 256 (1), 269-281 (2013).

- Walters, K. B., Green, J. M., Surfus, J. C., Yoo, S. K., Huttenlocher, A. Live imaging of neutrophil motility in a zebrafish model of WHIM syndrome. Blood. 116 (15), 2803-2811 (2010).

- Yoo, S. K., et al. Differential regulation of protrusion and polarity by PI3K during neutrophil motility in live zebrafish. Dev Cell. 18 (2), 226-236 (2010).

- Yoo, S. K., Huttenlocher, A. Spatiotemporal photolabeling of neutrophil trafficking during inflammation in live zebrafish. J Leukoc Biol. 89 (5), 661-667 (2011).

- Yoo, S. K., et al. The role of microtubules in neutrophil polarity and migration in live zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 125 (23), 5702-5710 (2012).

- Winata, C. L., et al. Development of zebrafish swimbladder: The requirement of Hedgehog signaling in specification and organization of the three tissue layers. Dev Biol. 331 (2), 222-236 (2009).

- Perry, S. F., Wilson, R. J., Straus, C., Harris, M. B., Remmers, J. E. Which came first, the lung or the breath?. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 129 (1), 37-47 (2001).

- Gratacap, R. L., Bergeron, A. C., Wheeler, R. T. Modeling mucosal candidiasis in larval zebrafish by swimbladder injection. J Vis Exp. (93), e52182 (2014).

- Adatto, I., Lawrence, C., Thompson, M., Zon, L. I. A New System for the Rapid Collection of Large Numbers of Developmentally Staged Zebrafish Embryos. PLoS ONE. 6 (6), e21715 (2011).

- Manicassamy, B., et al. Analysis of in vivo dynamics of influenza virus infection in mice using a GFP reporter virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107 (25), 11531-11536 (2010).

- Lawrence, C. The husbandry of zebrafish (Danio rerio): a review. Aquaculture. 269 (1), 1-20 (2007).

- Lam, P. -. y., Harvie, E. A., Huttenlocher, A. Heat Shock Modulates Neutrophil Motility in Zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 8 (12), e84436 (2013).

- Shelton, M. J., et al. Zanamivir pharmacokinetics and pulmonary penetration into epithelial lining fluid following intravenous or oral inhaled administration to healthy adult subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 55 (11), 5178-5184 (2011).

- Sullivan, C., Kim, C. H. Zebrafish as a model for infectious disease and immune function. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 25 (4), 341-350 (2008).

- MacRae, C. A., Peterson, R. T. Zebrafish as tools for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 14 (10), 721-731 (2015).

- Brandes, M., Klauschen, F., Kuchen, S., Germain, R. N. A systems analysis identifies a feedforward inflammatory circuit leading to lethal influenza infection. Cell. 154 (1), 197-212 (2013).

- Narasaraju, T., et al. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to acute lung injury of influenza pneumonitis. Am J Pathol. 179 (1), 199-210 (2011).

- Pillai, P. S., et al. Mx1 reveals innate pathways to antiviral resistance and lethal influenza disease. Science. 352 (6284), 463-466 (2016).

- Stifter, S. A., et al. Functional Interplay between Type I and II Interferons Is Essential to Limit Influenza A Virus-Induced Tissue Inflammation. PLoS Pathog. 12 (1), e1005378 (2016).

- Vlahos, R., Stambas, J., Selemidis, S. Suppressing production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) for influenza A virus therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 33 (1), 3-8 (2012).

- Palic, D., Andreasen, C. B., Ostojic, J., Tell, R. M., Roth, J. A. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) whole kidney assays to measure neutrophil extracellular trap release and degranulation of primary granules. J Immunol Methods. 319 (1-2), 87-97 (2007).

- Renshaw, S. A., et al. A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood. 108 (13), 3976-3978 (2006).

- Mathias, J. R., et al. Characterization of zebrafish larval inflammatory macrophages. Dev Comp Immunol. 33 (11), 1212-1217 (2009).

- Pase, L., et al. Neutrophil-delivered myeloperoxidase dampens the hydrogen peroxide burst after tissue wounding in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 22 (19), 1818-1824 (2012).

- Drescher, B., Bai, F. Neutrophil in viral infections, friend or foe?. Virus Res. 171 (1), 1-7 (2013).

- Iwasaki, A., Pillai, P. S. Innate immunity to influenza virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 14 (5), 315-328 (2014).

- Kolaczkowska, E., Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 13 (3), 159-175 (2013).

- Summers, C., et al. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 31 (8), 318-324 (2010).

- Tate, M. D., Brooks, A. G., Reading, P. C. The role of neutrophils in the upper and lower respiratory tract during influenza virus infection of mice. Respir Res. 9, 57 (2008).

- Tate, M. D., et al. Neutrophils ameliorate lung injury and the development of severe disease during influenza infection. J Immunol. 183 (11), 7441-7450 (2009).

- Tumpey, T. M., et al. Pathogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus: functional roles of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in limiting virus replication and mortality in mice. J Virol. 79 (23), 14933-14944 (2005).

- Wheeler, J. G., Winkler, L. S., Seeds, M., Bass, D., Abramson, J. S. Influenza A virus alters structural and biochemical functions of the neutrophil cytoskeleton. J Leukoc Biol. 47 (4), 332-343 (1990).

- de Oliveira, S., et al. Cxcl8-l1 and Cxcl8-l2 are required in the zebrafish defense against Salmonella Typhimurium. Dev Comp Immunol. 49 (1), 44-48 (2015).

- Harvie, E. A., Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophils in host defense: new insights from zebrafish. J Leukoc Biol. 98 (4), 523-537 (2015).