Microiontophoresis and Micromanipulation for Intravital Fluorescence Imaging of the Microcirculation

Summary

Microiontophoresis entails movement of ions from a micropipette in response to a difference in electrical potential between the inside and outside of the micropipette. Biologically active molecules are thereby delivered in proportion to electrical current. We illustrate acetylcholine microiontophoresis in conjunction with micromanipulation to study endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the microcirculation.

Abstract

Microiontophoresis entails passage of current through a micropipette tip to deliver a solute at a designated site within an experimental preparation. Microiontophoresis can simulate synaptic transmission1 by delivering neurotransmitters and neuropeptides onto neurons reproducibly2. Negligible volume (fluid) displacement avoids mechanical disturbance to the experimental preparation. Adapting these techniques to the microcirculation3 has enabled mechanisms of vasodilation and vasoconstriction to be studied at the microscopic level in vivo4,5. A key advantage of such localized delivery is enabling vasomotor responses to be studied at defined sites within a microvascular network without evoking systemic or reflexive changes in blood pressure and tissue blood flow, thereby revealing intrinsic properties of microvessels.

A limitation of microiontophoresis is that the precise concentration of agent delivered to the site of interest is difficult to ascertain6. Nevertheless, its release from the micropipette tip is proportional to the intensity and duration of the ejection current2,7, such that reproducible stimulus-response relationships can be readily determined under defined experimental conditions (described below). Additional factors affecting microiontophoretic delivery include solute concentration and its ionization in solution. The internal diameter of the micropipette tip should be ˜ 1 μm or less to minimize diffusional ‘leak’, which can be counteracted with a retaining current. Thus an outward (positive) current is used to eject a cation and a negative current used to retain it within the micropipette.

Fabrication of micropipettes is facilitated with sophisticated electronic pullers8. Micropipettes are pulled from glass capillary tubes containing a filament that ‘wicks’ solution into the tip of the micropipette when filled from the back end (“backfilled”). This is done by inserting a microcapillary tube connected to a syringe containing the solution of interest and ejecting the solution into the lumen of the micropipette. Micromanipulators enable desired placement of micropipettes within the experimental preparation. Micromanipulators mounted on a movable base can be positioned around the preparation according to the topography of microvascular networks (developed below).

The present protocol demonstrates microiontophoresis of acetylcholine (ACh+ Cl–) onto an arteriole of the mouse cremaster muscle preparation (See associated protocol: JoVE ID#2874) to produce endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Stimulus delivery is synchronized with digitized image acquisition using an electronic trigger. The use of Cx40BAC-GCaMP2 transgenic mice9 enables visualization of intracellular calcium responses underlying vasodilation in arteriolar endothelial cells in the living microcirculation.

Protocol

1. Animal Care and Use

Following review and approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, male mice at least 12 weeks old are used. A mouse is anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Throughout surgical procedures and experimental protocols, anesthesia is maintained by supplements (10-20% of initial injection, i.p.) as needed (every 30-60 minutes; indicated by withdrawal response to toe or tail pinch). After completion of the experimental procedure the mouse is overdosed with pentobarbital (i.p.) and euthanized by cervical dislocation.

2. Micropipettes and Microiontophoresis

- Microiontophoresis micropipettes (internal tip diameter, ˜1 μm) are prepared from borosilicate glass capillary tubes using a horizontal pipette puller. Ours have a ˜5 mm taper for stiffness; longer tapers are more flexible.

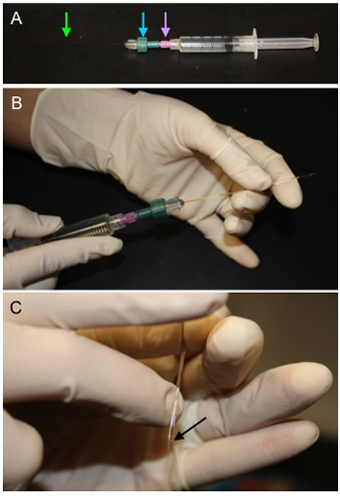

- Micropipettes are backfilled with 1M ACh (Figure1A-C) dissolved in 18.2 MΩ water. For backfilling, a microcapillary tube is connected to 0.2 μm filter coupled to a syringe containing the agonist of interest (Figure 1). These can be readily fabricated (below) or purchased from commercial vendors. The microcapillary tube is inserted into the back end of the micropipette and ACh solution is delivered into the lumen while withdrawing the microcapillary tube as the micropipette fills. Holding the micropipette with its tip pointing down, air bubbles are removed by gently flicking the micropipette.

- The micropipette is secured in a holder mounted in a micromanipulator (Figure 2). The holder has a silver wire connecting the ACh solution within the micropipette to an external pin, which in turn is connected to the positive terminal of a microiontophoresis programmer. A second silver wire secured at the edge of the tissue preparation is connected to the negative terminal to complete the circuit as the tip of the micropipette is advanced into the physiological saline solution over the preparation.

- A retaining current is applied to prevent vasodilation (or fluorescent response) when the micropipette tip is positioned adjacent to the arteriolar wall. Retaining current will vary with the size of the micropipette tip (internal diameter = 1 μm) and agonist concentration but is highly reproducible for defined parameters (we use ˜200 nA for 1M ACh, 1 μm tip). The retaining current ceases coincident with delivery of ejection current via the electronic trigger (Supplementary Figure 1) synchronized with the onset of image acquisition.

3. Micromanipulation

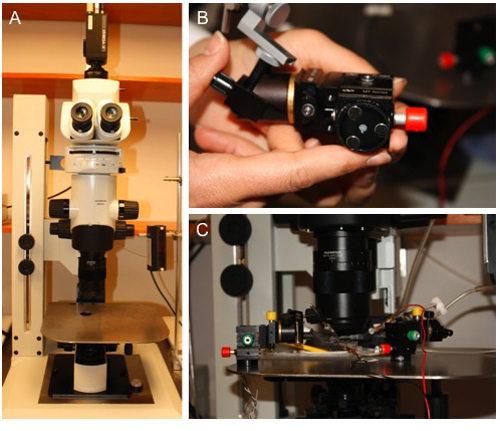

- A custom platform for an X-Y microscope stage was fabricated out of ferromagnetic stainless steel. Platform dimensions (1/8″ X 12″ X 13″) enable sufficient space to position micromanipulators around the experimental preparation as desired (Figure 2A). Micromanipulators secured to magnetic bases (Figure 2B) enable positioning as dictated by the preparation. These are placed directly on the fabricated platform around the preparation for positioning micropipettes at sites of interest (Figure 2C).

4. Representative Results

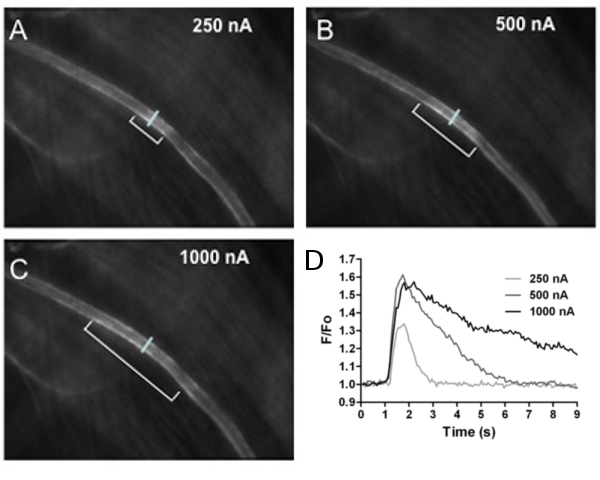

- With the micropipette tip positioned adjacent to an arteriole, there is fluorescence response to ACh (retaining current than adjusted to prevent ACh leakage). Below a threshold stimulus there was no effect. However, as stimulus intensity increased, endothelial cell calcium fluorescence increased over progressively greater distances along the arteriole, as did the intensity of fluorescence at the site of stimulation (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Method for Backfilling Microiontophoresis Pipettes. A) A microcapillary tube (green arrow) is secured in a compression fitting (blue arrow)

attached to a 0.2 μm filter (purple arrow) which is then attached to a syringe filled with 1M ACh. B) The microcapillary tube is fed into the

microiontophoresis pipette through the back end and solution is displaced to fill the lumen of the micropipette. C) Once the pipette is filled, hold the tip

down and gently flick above the taper to remove bubbles (black arrow).

Figure 2. Custom Platform for Micromanipulator Placement. A) A ferromagnetic stainless steel platform was placed on a custom MVX10 microscope base

containing an X-Y translational stage. B) Circular magnetic bases affixed to the bottom of compact 3-axis micromanipulators. C)

Micromanipulators positioned around the experimental preparation (See associated protocol: JoVE ID#2874) to study specific sites of interest. Their

compact size and versatility enable multiple micropipettes to be used simultaneously.

Figure 3. Calcium Fluorescence in Arterioles. Calcium fluorescence of endothelial cells lining the arteriolar wall increased with stimulus intensity.

The first 3 panels shown images of fluorescence responses to A) 250 nA, B) 500 nA and C) 1000 nA ejection current (all 500 ms pulse duration). The distance over which

endothelial cell calcium fluorescence increased is indicated by brackets in A-C (˜130, 270 and 400 μm, respectively). The reference line across the arteriole in each

panel indicates where fluorescence responses (F/Fo) to ACh were recorded at the site of stimulation. D) Recordings of F/Fo vs. time for increasing ACh stimuli. As

ejection current increased, F/Fo increased in amplitude and duration. Note that 100 nA stimulus was below threshold and had no effect.

Supplementary Figure 1. Circuit diagram for electronic trigger. This circuit is interfaced with a parallel port from a personal computer. When activated it provides a constant TTL pulse of 5V. The 7805 chip is a 5V voltage regulator connected to a 9-12V DC power supply (a battery of appropriate voltage is fine). Output from the 7805 provides power to the Quad Bilateral Switch and to the output of the circuit. Input across the 1K resistor is from the computer.

Discussion

The protocol described here demonstrates methods for preparing and implementing micropipettes for microiontophoresis. Delivery of acetylcholine is used to illustrate calcium signaling underlying endothelium-dependent vasodilation in arterioles of the anesthetized mouse. Our results illustrate that the distance over which ACh increases endothelial cell calcium fluorescence increases with the intensity of ejection current from the microiontophoresis micropipette (Figure 3). The lack of fluorescence increase under resting conditions indicates negligible leakage of ACh from the micropipette. The lack of response to 100 nA stimulus intensity (Figure 3, legend) illustrates that a threshold intensity of stimulation is required for endothelial cell calcium to increase. These techniques can be readily adapted to other vasoactive agents and tissue preparations.

Practical considerations: In working with microiontophoresis to study arteriolar reactivity, several things should be recognized. While it has proven difficult to determine the actual concentration of agonist delivered, stimulus-response curves are reproducible within and between preparations. These can be performed by holding pulse duration constant (e.g., 500 ms) and varying the ejection current (e.g., 250, 500 and 1000 nA; Figure 3). Alternatively, ejection current can be held constant (e.g., 500 nA) and pulse duration varied (e.g., 250, 500 and 1000 ms). For a reference to the actions of a defined agonist concentration, the preparation can be superfused with the appropriate solution5. Because the driving force for solute ejection is electrical charge movement, the agent to be delivered must carry a net charge to be displaced from the micropipette. To ensure that the agent of interest is the primary charge carrier, it is dissolved at high concentration (e.g., 1 M for ACh) to minimize electro-osmosis. When this requires manipulating the pH of the micropipette filling solution, vehicle controls are required to ascertain any nonspecific effects. Appropriate controls should also be performed for the passage of current alone (e.g., using micropipettes filled with isotonic saline). The effective distance for diffusion of the agent from its site of release should be ascertained and is most readily determined empirically by the disappearance of a physiological response (e.g., vasodilation or a rise in intracellular calcium upon ejection of ACh) as the micropipette is positioned at defined distances from the target site. In practice, the effective diffusion distance is greatly influenced by how the tip of the micropipette is positioned in the tissue; e.g. if the tip pressed down into the tissue and its tip is occluded, than ejection is impaired. Excessive connective tissue is particularly troublesome and should be removed from the tissue surface during surgical preparation. Attention should also be given to the possibility of depleting the tip of the designated agent. This is minimized by using relatively short pulses (e.g., ≤ 1 s). With sustained currents (e.g., several seconds), the agonist may be expelled from the tip more rapidly than it can be replaced by diffusion from the bulk filling solution in the micropipette.

Because negligible volume is displaced with microiontophoresis, if one is trying to change the local ionic milieu (e.g., to deliver a depolarizing K+ stimulus), this cannot be effectively accomplished with microiontophoresis but is readily achieved with pressure ejection of bulk fluid having the desired composition. For local stimulation of an arteriole, micropipette tips with internal diameters of 2-3 μm work well with ejection pressure 4-5 psi (28-35 kPa) and pulse duration (e.g., 1 second) controlled with a solenoid valve10. Where sustained delivery of an agent from a micropipette onto a microvessel is required, pressure ejection is preferred using micropipettes of appropriate internal tip diameter (e.g., ˜10 μm)11,12. A hydrostatic column of known height with a stopcock valve provides an inexpensive, well-defined on/off constant pressure head. Flow rates are determined by the inner diameter of the pipette tip and the driving pressure. As always, vehicle controls are essential to exclude nonspecific actions of pressure ejection.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R37-HL041026, R01-HL086483 and R01-HL056786 (SSS) and by F32-HL097463 and T32-AR048523 (PB) from the United States Public Health Service.

Materials

| Material Used | Company | Catalogue number | Comments |

| Borosilicate Glass Capillary Tubes | Warner Instruments | GC120F-10 | |

| Horizontal Pipette Puller | Sutter Instruments | model P-97 | |

| Acetylcholine Chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | A6625 | |

| adapter for Luer hub | Martech | AC1343 | To secure microcapillary tubing |

| 0.2 μm Nylon Titan filter | Sun Sri | 42204-NN | Low retention volume to minimize loss |

| 5 ml syringe | Becton-Dickinson Co. | 309603 | |

| Pipette Holder | Warner Instruments | E45W-M12VH | |

| Silver Wire | Warner Instruments | AG10W | 0.25mm diameter |

| 3-axis micromanipulator | Siskiyou Design Instruments | DT3-100, MXB, MXC, MGB/8 | Components for manipulator as shown |

| microiontophoresis current programmer | World Precision Instruments | Model 260 | |

| trigger device | Custom | custom | circuit provided in Suppl. Figure 1 |

| stainless steel plate | McMaster-Carr | 1/8″ X 12″ X 12″ | According to design |

| Intensified Digital Camera | Stanford Photonics Inc | XR/Mega-10 | Integrated with Piper Control software |

References

- Majno, G., Palade, G. E. Studies on inflammation. 1. The effect of histamine and serotonin on vascular permeability: an electron microscopic study. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 11, 571-605 (1961).

- Majno, G., Palade, G. E., Schoefl, G. I. Studies on inflammation. II. The site of action of histamine and serotonin along the vascular tree: a topographic study. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 11, 607-626 (1961).

- Grant, R. T. Direct Observation of Skeletal Muscle Blood Vessels (Rat Cremaster). J. Physiol. 172, 123-137 (1964).

- Baez, S. An open cremaster muscle preparation for the study of blood vessels by in vivo microscopy. Microvasc. Res. 5, 384-394 (1973).

- Bohlen, H. G., Gore, R. W., Hutchins, P. M. Comparison of microvascular pressures in normal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Microvasc. Res. 13, 125-130 (1977).

- Klitzman, B., Duling, B. R. Microvascular hematocrit and red cell flow in resting and contracting striated muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 237, 481-490 (1979).

- Hungerford, J. E., Sessa, W. C., &, S. e. g. a. l., S, S. Vasomotor control in arterioles of the mouse cremaster muscle. FASEB J. 14, 197-207 (2000).

- Figueroa, X. F., Paul, D. L., Simon, A. M., Goodenough, D. A., Day, K. H., Damon, D. N., Duling, B. R. Central role of connexin40 in the propagation of electrically activated vasodilation in mouse cremasteric arterioles in vivo. Circ. Res. 92, 793-800 (2003).

- Wolfle, S. E., Schmidt, V. J., Hoepfl, B., Gebert, A., Alcolea, S., Gros, D., de Wit, C. Connexin45 cannot replace the function of connexin40 in conducting endothelium-dependent dilations along arterioles. Circ. Res. 101, 292-1299 (2007).

- Milkau, M., Kohler, R., de Wit, C. Crucial importance of the endothelial K+ channel SK3 and connexin40 in arteriolar dilations during skeletal muscle contraction. FASEB J. 24, 3572-3579 (2010).

- Bagher, P., Duan, D., Segal, S. S. Evidence for impaired neurovascular transmission in a murine model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Appl. Physiol. 110, 601-610 (2011).

- Tallini, Y. N., Brekke, J. F., Shui, B., Doran, R., Hwang, S. M., Nakai, J., Salama, G., Segal, S. S., Kotlikoff, M. I. Propagated endothelial Ca2+ waves and arteriolar dilation in vivo: measurements in Cx40BAC-GCaMP2 transgenic mice. Circ. Res. 101, 1300-1309 (2007).

- Grant, R. T. The effects of denervation on skeletal muscle blood vessels (rat cremaster). J. Anat. 100, 305-316 (1966).

- Proctor, K. G., Busija, D. W. Relationships among arteriolar, regional, and whole organ blood flow in cremaster muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 249, H34-H41 (1985).

- Bagher, P., Segal, S. S. Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation: Role of conducted vasodilation. Acta Physiol. , (2011).

- Hill, M. A., Simpson, B. E., Meininger, G. A. Altered cremaster muscle hemodynamics due to disruption of the deferential feed vessels. Microvasc. Res. 39, 349-363 (1990).