Peripheral Vascular Exam

64,893 Views

•

•

Overview

Source: Joseph Donroe, MD, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) increases with age and is a significant cause of morbidity in older patients, and peripheral artery disease (PAD) is associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and tobacco use are important disease risk factors. When patients become symptomatic, they frequently complain of limb claudication, defined as a cramp-like muscle pain that worsens with activity and improves with rest. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) often present with lower extremity swelling, pain, skin changes, and ulceration.

While the benefits of screening asymptomatic patients for PVD are unclear, physicians should know the proper exam technique when the diagnosis of PVD is being considered. This video reviews the vascular examination of the upper and lower extremities and abdomen. As always, the examiner should use a systematic method of examination, though in practice, the extent of the exam a physician performs depends on their suspicion of underlying PVD. In a patient who has or is suspected to have risk factors for vascular disease, the vascular exam should be thorough, beginning with inspection, followed by palpation, and then auscultation, and it should include special maneuvers, such as determining the ankle brachial index. Maneuvers that make use of a handheld Doppler are demonstrated in a companion video.

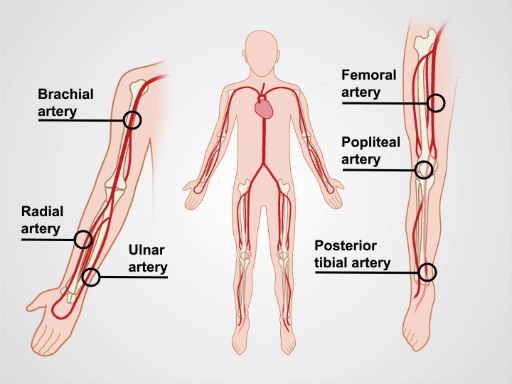

Figure 1. The major arm and leg arteries.

Procedure

1. Preparation

- Wash your hands prior to examining the patient.

- Have the patient put on a gown. This examination should never occur through clothing.

- Check the blood pressure in both arms.

2. The Upper Extremities

- Have the patient lie supine on the exam table, with the head raised to a comfortable position.

- Begin with inspection by exposing the entirety of both arms. Note symmetry, color, hair pattern, size, skin changes, nail changes, varicosities, muscle wasting, and trauma (Table 1).

- Palpate by using the back of the fingers to assess skin temperature. Examine from distal to proximal, comparing one side to the other.

- Assess capillary refill by applying firm pressure over the distal 1st or 2nd digit for 5 sec. Release pressure and count how many seconds it takes for the normal skin color to return. A normal capillary refill time (CRT) is less than 2 sec, and values greater than 5 sec increase the likelihood of vascular disease. Additionally, CRT may be prolonged in hypovolemia and cooler ambient temperatures.

- Palpate for edema over the dorsum of the hands using firm pressure for at least 2 sec. If present, palpate proximally, noting the extent and distribution of the edema, and whether or not it is pitting. Grade the edema as trace, mild, moderate, or severe.

- Palpate the major arteries and note the symmetry, the intensity, and the regularity of the pulse. Useful terminology to describe the pulse intensity includes absent, diminished, normal, or bounding. If unsure, compare the patient's pulse to your own pulse. Use anatomical landmarks to find the pulse. If no pulse is felt, vary the pressure, then adjust your position, as there is variability in the path of each artery.

- Palpate the radial arteries, which lie lateral to the flexor carpi radialis tendon.

- Palpate the ulnar arteries, which are just lateral to the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon.

- Palpate the brachial arteries in the antecubital fossa, medial to the biceps tendon. The artery can be followed proximally in the medial groove between the biceps and triceps muscles.

3. The Abdomen

- Lower the head of the table so the patient is lying flat.

- Inspect the abdomen for dilated veins. Dilated veins around the umbilicus may be due to portal hypertension or obstruction of the inferior vena cava (IVC).

- For dilated superficial veins, determine the direction of filling by using a finger to compress the vein proximally.

- Use a second finger to strip the blood distally from the vein and then leave the finger in place, thus compressing two points along the flattened vein.

- Remove the proximal finger and note the speed at which the vein refills.

- Repeat the process; however, remove the distal finger and compare the filling speed. Note the direction of the fast filling, which is away from the source of venous hypertension.

- Palpate for the abdominal aorta, just above the umbilicus and slightly left of the midline. Use 3 to 4 finger pads of both hands to apply slow and steady downward pressure. The hands should point cephalad and slightly toward each other.

- Once the pulse is encountered, gradually bring the fingertips closer together until the lateral walls of the aorta are felt. Measure the distance between the fingers.

- Next,auscultatefor bruits using the diaphragm of the stethoscope, applying moderate pressure. A bruit with a systolic and diastolic component is more likely to be pathologic than a systolic bruit alone.

- Auscultate the renal arteries above the umbilicus and 1" to 2" lateral to the midline.

- Auscultate the abdominal aorta above the umbilicus and to the left of the midline.

- Auscultate the iliac arteries below the umbilicus and 1" to 2" lateral to the midline.

4. The Lower Extremities.

- Begin with inspection by exposing the entirety of both legs, but leave the genitalia covered. Look for changes as described in Step 2.2 and Table 1.

- Palpate for temperature, CRT, edema, and arteries, as described in Step 2.3.

- Palpate the dorsalis pedis (DP) arteries, just lateral to the extensor hallucis longus tendon. One or both DP arteries may be congenitally absent in a small percentage of patients.

- Palpate the posterior tibialis (PT) arteries at the posterior-inferior aspect of the medial malleolus.

- Palpate the popliteal arteries, beginning with the leg slightly flexed at the knee. Place both thumbs on the patellar ligament and wrap your fingers around the knee, such that the fingertips land in the middle of the popliteal fossa. If there is difficulty identifying the pulse, gradually flex the knee in 15° intervals while continuing to palpate. If unable to encounter the pulse in this position, have the patient turn to the prone position, flex the knee, and support the lower extremity. Place your hands on either side of the knee and use the thumbs to palpate the popliteal artery.

- Palpate the femoral arteries, just inferior to the inguinal ligament, approximately midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis.

- Auscultate the femoral arteries using the bell or diaphragm of the stethoscope, using light pressure, so as not to artificially induce a bruit.

| Finding | Peripheral Arterial Disease | Chronic Venous Insufficiency |

| Edema | Absent or mild | Present, unilateral, or bilateral |

| Ulcers | Well demarcated, often distal leg, dorsum of foot, toes (trauma sites) | Irregular margins, often over anterior shin and medial malleolus |

| Hair Distribution | Decreased | No change |

| Color | Pallor (acute), dependent hyperemia (chronic), distal gangrene (severe) | Brown-red hyperpigmentation |

| Nails | Decreased growth, thickened | Thickened, darkened, onychomycosis |

| Varicose Veins | Absent | Present |

| Muscle Atrophy | May be present | Difficult to detect due to significant edema |

| Skin Appearance | Thin, shiny, atrophic | Thickened, scaly |

| Temperature | Cool | No change |

Table 1. Skin changes associated with peripheral vascular disease.

5. Special Maneuvers

- Use the Allen test prior to cannulating the radial artery to ensure adequate collateral flow through the palmar arch from the ulnar artery.

- Begin by palpating the ulnar and radial arteries on the side.

- Ask the patient to make a tight fist.

- Apply sufficient pressure over the ulnar and radial arteries to occlude them.

- Ask the patient to open the fist, and note the pallor of the palm.

- Release the ulnar artery. If sufficient collateral flow is present, the palm should become pink again within 3 to 5 sec.

- Use Buerger's test to assess for PAD of the lower extremities, and it may also be useful for predicting the severity of the disease. With the patient supine, elevate the legs to 60° for 2 min or until the pallor of the distal extremity is noted.

- Lower the legs and allow them to dangle below the table's edge. Observe for 2 min or until a hyperemia is observed over the dorsum of the foot, indicating arterial insufficiency.

- Perform the following maneuvers in patients with varicose veins to localize the site of incompetent valves.

- Perform the Brodie-Trendelenburg test with the patient in the supine position.

- Elevate the leg of interest and strip the blood proximally out of the great saphenous vein (GSV).

- Compress the GSV just below the sapheno-femoral junction (SFJ), and ask the patient to stand.

- Observe the filling of the GSV, which under normal circumstances, fills distal to proximal and takes 20 to 30 sec. Rapid filling with the GSV occluded suggests insufficiency of the perforating veins.

- Release the pressure over the GSV. Accelerated filling suggests venous insufficiency at the level of the SFJ.

- Perform the cough test to detect reflux at the SFJ. With the patient standing, palpate over the SFJ with light pressure.

- Instruct the patient to cough. A palpable thrill suggests retrograde flow and venous insufficiency.

- To perform the Perthes test, place a tourniquet around the leg, just below the knee.

- Instruct the patient to perform 10 heel raises. Emptying of the varicose veins suggests incompetence above the level of the tourniquet (SFJ, sapheno-popliteal junction, or thigh perforating veins). If the veins remain distended, the site of insufficiency is the calf perforating veins.

- Perform the Brodie-Trendelenburg test with the patient in the supine position.

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease increases with age and it is a significant cause of morbidity in older patients. The peripheral vascular exam plays a key role in bedside diagnosis of this condition.

Peripheral vascular disease, or PVD, includes peripheral artery disease, abbreviated as PAD, and chronic venous insufficiency, or CVI. PAD refers to the narrowing of the peripheral arterial blood vessels primarily caused by the accumulation of fatty plaques, or atherosclerosis. When patients with PAD become symptomatic, they frequently complain of limb claudication defined as a cramp-like muscle pain that worsens with activity and improves with rest. On the other hand, CVI is a condition in which peripheral vein walls become less flexible and dilated, and the one-way valves do not work effectively to prevent the reverse flow. Thus, leading to pooling of blood in the extremities. Patients with CVI often present with lower extremity swelling, pain, skin changes, and ulceration.

When the diagnosis of PVD is being considered, every examiner should follow the proper peripheral vascular exam technique, though the extent of the exam depends on the suspicion of the underlying PVD. This video reviews the general steps for the vascular examination of the upper extremities, the abdomen, and the lower extremities.

Let’s go over the steps involved in a comprehensive peripheral vascular physical examination. Prior to the examination, have the patient put on a gown. This investigation should never occur through clothing. Wash your hands thoroughly before meeting the patient.

Upon entering the room, first introduce yourself and briefly explain the procedure you’re going to conduct. Check the patient’s blood pressure is in both arms. After recording the blood pressure, start with the vascular exam of the upper extremities. Request the patient to lie supine on the exam table with the head raised to a comfortable position. Expose the entirety of both arms and begin with visual inspection. Note symmetry, color, hair pattern, size, skin changes, nail changes, varicosities, muscle wasting, and trauma.

Next, palpate by using the back of the fingers to assess skin temperature. Examine from distal to proximal, comparing one side to the other. Then, assess capillary refill by applying firm pressure over the distal first or second digit for five seconds. Release pressure and count how many seconds it takes for the normal skin color to return. Normal capillary refill time is less than 2 seconds. Following that, palpate for edema over the dorsum of the hands using firm pressure for at least two seconds. If present, palpate proximally, noting the extent and distribution of the edema, and whether or not it is pitting. Grade the edema as trace or mild, which is 1+; moderate or 2+; or severe that is 3+.

Next, palpate the major arteries of the upper extremities. Always use the surface anatomical landmarks to find the pulse. Start by locating the flexor carpi radialis tendon and lateral to that palpate the radial artery. While palpating, note the intensity, rhythm, and symmetry as compared to the other side. Intensity can be described as absent, diminished, normal, or bounding. If unsure, compare the patient’s pulse to your own pulse. Subsequently, locate the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and slightly lateral to it palpate the ulnar artery. Next, medial to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa, palpate the brachial artery. This artery can be followed proximally in the medial groove between the biceps and triceps muscles. For any artery, if no pulse is felt, vary the pressure, and then adjust your position, as there is variability in the path of each artery.

Lastly, if you planning to cannulate the radial artery, perform the Allen’s test. Ask the patient to make a fist and apply sufficient pressure over the ulnar and radial arteries to occlude them. Then instruct the patient to open the fist and note the pallor of the palm. Release the ulnar artery; if sufficient collateral flow is present, the palm should become pink again within 3 to 5 sec. Here we see a sluggish collateral flow, while on the other hand of the collateral flow was good. This concludes the vascular exam of the upper extremities.

Now let’s move to the abdomen. Start by lowering the head of the table so that the patient is lying flat. Adjust the gown to allow sufficient exposure of the abdominal area. First, inspect for dilated veins. If present, follow the procedure described in the text below. Next, locate the abdominal aorta, which is just above the umbilicus and slightly left of the midline. Then, palpate using three to four finger pads of both hands to apply slow and steady downward pressure. The hands should point cephalad and slightly toward each other. Once the pulse is encountered, gradually bring the fingertips closer together until the lateral walls of the aorta are felt. Approximate the distance between the fingers, which is normally less than 3 cm. Following palpation, use the diaphragm of the stethoscope to auscultate the aorta for bruits, while applying moderate pressure. Also, auscultate the renal arteries above the umbilicus and one to two inches lateral to the midline, followed by the iliac arteries below the umbilicus and one to two inches lateral to the midline.

The last part of the vascular exam involves the lower extremities. Begin with inspection, by exposing the entirety of both legs, leaving the genitalia covered. Similar to upper extremities, look for changes in symmetry, color, hair pattern, size, skin changes, nail changes, varicosities, muscle wasting, and trauma. Also, palpate for temperature, perform the capillary refill test, and palpate for the presence of edema. This patient had a non-pitting edema of left leg.

Thereafter, begin with the palpation of the major leg arteries. First, locate the extensor hallucis longus tendon, and palpate the dorsalis pedis artery, which lies just lateral to the tendon. Next, pinpoint the medial malleolus, and posterior and inferior to the malleolus you’ll find the posterior tibialis artery. After that, palpate the popliteal arteries. Place both thumbs on the patellar tendon, slightly flex the patient’s knee and wrap your fingers such that the fingertips land in the middle of the popliteal fossa. If there is difficulty identifying the pulse, gradually flex the knee in 15° intervals while continuing to palpate. If unable to encounter the pulse in this position, have the patient turn to the prone position, flex the knee, and support the lower extremity. Now place your hands on either side of the knee and use the thumbs to palpate the popliteal artery. Next, palpate the femoral arteries, just inferior to the inguinal ligament, approximately midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis. Lastly, auscultate the femoral arteries using the bell or diaphragm, while applying light pressure, so as not to artificially induce a bruit.

“This concludes the general peripheral vascular exam. There are other maneuvers that can be done for patients with suspected peripheral vascular disease. However, in reality, these are rarely performed in the office, particularly when imaging is available. These maneuvers include the Buerger’s test for peripheral artery disease. And the Brodie-Trendelenburg test, cough test and the Perthes test for patients with varicose veins. The procedures describing these maneuvers can be found in the accompanying text.”

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on the peripheral vascular exam. This video reviewed a systematic method and proper technique of vascular examination of the extremities and the abdomen. Like all aspects of the physical exam, practice is critical for improving accuracy of vascular assessment. In addition, an understanding of relevant anatomy is important for correct interpretation of the findings. As always, thanks for watching!

Applications and Summary

Peripheral vascular disease is an important cause of morbidity, particularly in older patients. The detection and subsequent treatment of PVD can improve quality of life and potentially mitigate cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. General screening for peripheral vascular disease of the extremities is not a current recommendation by the US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF). However, the USPSTF does recommend ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in males who have smoked and are aged 65 to 75. Additionally, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology recommends a comprehensive vascular exam in anyone at risk of PVD.

The most important findings that make PAD more likely in a patient include characteristic ulcers, asymmetric temperature difference in the foot, absent pulses, and limb bruits. The most important finding that argues against significant PAD is the presence of at least one pedal pulse on a given leg. A positive Buerger's test increases the likelihood of more extensive disease. Of the physical exam maneuvers to localize the site of reflux in patients with varicose veins, Perthes and Brodie-Trendelenburg tests are the most helpful for ruling out a particular location as the site of reflux. The overall accuracy of these venous reflux maneuvers is limited, however, and detection of the site of reflux is improved through use of a handheld Doppler.

This video reviewed a systematic method and proper technique of vascular examination of the extremities and abdomen, and included a review of special diagnostic maneuvers that should be performed if PVD is suspected. Like all aspects of the physical exam, practice is critical for improving accuracy, and an understanding of the relevant anatomy is important to a successful examination and interpretation of the exam findings.

Transcript

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease increases with age and it is a significant cause of morbidity in older patients. The peripheral vascular exam plays a key role in bedside diagnosis of this condition.

Peripheral vascular disease, or PVD, includes peripheral artery disease, abbreviated as PAD, and chronic venous insufficiency, or CVI. PAD refers to the narrowing of the peripheral arterial blood vessels primarily caused by the accumulation of fatty plaques, or atherosclerosis. When patients with PAD become symptomatic, they frequently complain of limb claudication defined as a cramp-like muscle pain that worsens with activity and improves with rest. On the other hand, CVI is a condition in which peripheral vein walls become less flexible and dilated, and the one-way valves do not work effectively to prevent the reverse flow. Thus, leading to pooling of blood in the extremities. Patients with CVI often present with lower extremity swelling, pain, skin changes, and ulceration.

When the diagnosis of PVD is being considered, every examiner should follow the proper peripheral vascular exam technique, though the extent of the exam depends on the suspicion of the underlying PVD. This video reviews the general steps for the vascular examination of the upper extremities, the abdomen, and the lower extremities.

Let’s go over the steps involved in a comprehensive peripheral vascular physical examination. Prior to the examination, have the patient put on a gown. This investigation should never occur through clothing. Wash your hands thoroughly before meeting the patient.

Upon entering the room, first introduce yourself and briefly explain the procedure you’re going to conduct. Check the patient’s blood pressure is in both arms. After recording the blood pressure, start with the vascular exam of the upper extremities. Request the patient to lie supine on the exam table with the head raised to a comfortable position. Expose the entirety of both arms and begin with visual inspection. Note symmetry, color, hair pattern, size, skin changes, nail changes, varicosities, muscle wasting, and trauma.

Next, palpate by using the back of the fingers to assess skin temperature. Examine from distal to proximal, comparing one side to the other. Then, assess capillary refill by applying firm pressure over the distal first or second digit for five seconds. Release pressure and count how many seconds it takes for the normal skin color to return. Normal capillary refill time is less than 2 seconds. Following that, palpate for edema over the dorsum of the hands using firm pressure for at least two seconds. If present, palpate proximally, noting the extent and distribution of the edema, and whether or not it is pitting. Grade the edema as trace or mild, which is 1+; moderate or 2+; or severe that is 3+.

Next, palpate the major arteries of the upper extremities. Always use the surface anatomical landmarks to find the pulse. Start by locating the flexor carpi radialis tendon and lateral to that palpate the radial artery. While palpating, note the intensity, rhythm, and symmetry as compared to the other side. Intensity can be described as absent, diminished, normal, or bounding. If unsure, compare the patient’s pulse to your own pulse. Subsequently, locate the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and slightly lateral to it palpate the ulnar artery. Next, medial to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa, palpate the brachial artery. This artery can be followed proximally in the medial groove between the biceps and triceps muscles. For any artery, if no pulse is felt, vary the pressure, and then adjust your position, as there is variability in the path of each artery.

Lastly, if you planning to cannulate the radial artery, perform the Allen’s test. Ask the patient to make a fist and apply sufficient pressure over the ulnar and radial arteries to occlude them. Then instruct the patient to open the fist and note the pallor of the palm. Release the ulnar artery; if sufficient collateral flow is present, the palm should become pink again within 3 to 5 sec. Here we see a sluggish collateral flow, while on the other hand of the collateral flow was good. This concludes the vascular exam of the upper extremities.

Now let’s move to the abdomen. Start by lowering the head of the table so that the patient is lying flat. Adjust the gown to allow sufficient exposure of the abdominal area. First, inspect for dilated veins. If present, follow the procedure described in the text below. Next, locate the abdominal aorta, which is just above the umbilicus and slightly left of the midline. Then, palpate using three to four finger pads of both hands to apply slow and steady downward pressure. The hands should point cephalad and slightly toward each other. Once the pulse is encountered, gradually bring the fingertips closer together until the lateral walls of the aorta are felt. Approximate the distance between the fingers, which is normally less than 3 cm. Following palpation, use the diaphragm of the stethoscope to auscultate the aorta for bruits, while applying moderate pressure. Also, auscultate the renal arteries above the umbilicus and one to two inches lateral to the midline, followed by the iliac arteries below the umbilicus and one to two inches lateral to the midline.

The last part of the vascular exam involves the lower extremities. Begin with inspection, by exposing the entirety of both legs, leaving the genitalia covered. Similar to upper extremities, look for changes in symmetry, color, hair pattern, size, skin changes, nail changes, varicosities, muscle wasting, and trauma. Also, palpate for temperature, perform the capillary refill test, and palpate for the presence of edema. This patient had a non-pitting edema of left leg.

Thereafter, begin with the palpation of the major leg arteries. First, locate the extensor hallucis longus tendon, and palpate the dorsalis pedis artery, which lies just lateral to the tendon. Next, pinpoint the medial malleolus, and posterior and inferior to the malleolus you’ll find the posterior tibialis artery. After that, palpate the popliteal arteries. Place both thumbs on the patellar tendon, slightly flex the patient’s knee and wrap your fingers such that the fingertips land in the middle of the popliteal fossa. If there is difficulty identifying the pulse, gradually flex the knee in 15° intervals while continuing to palpate. If unable to encounter the pulse in this position, have the patient turn to the prone position, flex the knee, and support the lower extremity. Now place your hands on either side of the knee and use the thumbs to palpate the popliteal artery. Next, palpate the femoral arteries, just inferior to the inguinal ligament, approximately midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis. Lastly, auscultate the femoral arteries using the bell or diaphragm, while applying light pressure, so as not to artificially induce a bruit.

“This concludes the general peripheral vascular exam. There are other maneuvers that can be done for patients with suspected peripheral vascular disease. However, in reality, these are rarely performed in the office, particularly when imaging is available. These maneuvers include the Buerger’s test for peripheral artery disease. And the Brodie-Trendelenburg test, cough test and the Perthes test for patients with varicose veins. The procedures describing these maneuvers can be found in the accompanying text.”

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on the peripheral vascular exam. This video reviewed a systematic method and proper technique of vascular examination of the extremities and the abdomen. Like all aspects of the physical exam, practice is critical for improving accuracy of vascular assessment. In addition, an understanding of relevant anatomy is important for correct interpretation of the findings. As always, thanks for watching!