- 00:07Descripción

- 01:26Principles of the MSMPR Model

- 03:58Experimental Preparation

- 04:59Crystallizer Start-up

- 06:27Sample Collection and Crystallizer Shut Down

- 07:39Data Analysis

- 08:57Calculations and Results

- 10:11Applications

- 11:21Summary

水杨酸的化学改性结晶

English

Compartir

Descripción

资料来源: 凯瑞先生和迈克尔 g. 本顿, 路易斯安那州立大学化学工程系, 巴吞鲁日, LA

加工生化涉及的单位操作, 如结晶, 离心, 膜过滤, 和制备色谱, 所有这些都有共同的需要分离大的小分子, 或固体从液体。其中, 从吨位的角度来看, 结晶是最重要的。由于这个原因, 它通常被用于制药、化学和食品加工行业。重要的生物化学例子包括手性分离,1纯化抗生素,2从前体分离氨基酸,3和许多其他药剂,4-5食品添加剂,6-7和农用化学品净化.8晶体形态和尺寸分布的控制是过程经济学的关键, 因为这些因素影响下游加工操作的成本, 如干燥、过滤和固体输送。有关结晶的更多信息, 请参考专业教科书或单元操作教科书。9

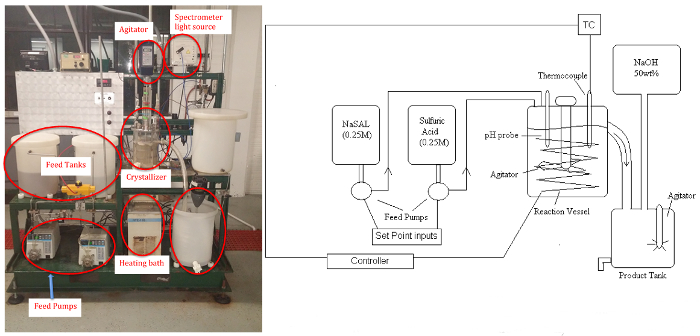

结晶器单元 (图 1) 能够研究: (a) 主要参数, 如过饱和和冷却/升温速率, 对固体含量, 形态和晶体尺寸分布的影响;(b) 和对结晶过程的在线控制。过饱和度可以通过搅拌速率和温度等改变条件来控制。不同的结晶分类包括冷却、蒸发、pH 摆动和化学改性。在这个实验中, 离线显微镜将测量从大小从10-1000 μ m, 一个典型的大小范围为生物制品。

图 1:& 标识示意图 (左) 和结晶器 (右图)。请单击此处查看此图的较大版本.

这项实验将显示 “化学修饰”, 或 “pH 摆动” 结晶, 以产生水杨酸 (萨尔) (前体阿司匹林) 晶体的水溶液的快速反应碱性水杨酸钠 (鼻), 这是基本的,硫酸 (H2,4) 在任何地方从 40-80 ° c。11

Na+萨尔+ 0.5 H24 SAL (ppt) + Na+ + 0.5 所以42-

副产物硫酸钠仍然是可溶解的。该装置由两个进给罐, 三变速 (蠕动) 泵, 结晶器 (搅拌槽, 以接近均匀的温度和浓度, 〜5升), 一个循环浴缸的温度控制, 功率控制器, 产品罐, 和用氢氧化钠溶液进行饲料再生的化妆箱 (如果需要)。用紫外-可见光谱仪对水杨酸的残留可溶性离子进行分析, 并对水杨酸结晶产物进行干燥和称量。pH 探针可用于确定反应条件改变时的稳态。

Principios

Procedimiento

Resultados

Figure 2 presents representative data that suggests modest deviations from the crystal size distribution of the MSMPR ideal even at relatively high speeds and low feed concentrations.

Figure 2. Crystal size distribution for 0.16 M NaSAL feed, 540 rpm, 60 ° C

The crystals that form from this experiment are typically needle shaped, and the length distribution can be determined microscopically. Sample lengths with size dimensions (in microns) of typical crystals are shown in Figure 3. The normal and preferred range of crystals is 100-1000 microns.

Figure 3. Magnified salicylic acid crystals. The sizes are in microns. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Assuming the equations of the MSMPR crystallizer (1-4), and using a mass balance on salicylate, runs the concentration of solid crystals in the magma (CSAL), the residence times (τ), growth rate functions G, amounts of supersaturation in the aqueous phase ΔC on a molar basis, nucleation function B0, and the crystal yields on both a product and a feed basis were determined. The G-function was computed from Equation (3) using the size distribution. And the supersaturation and mass balance equations are:

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

where Q1 is the volumetric flow rate of the NaSAL solution, Qt is total volumetric flow rate, (CNaSAL)0 is the feed concentration of NaSAL in Q1, and CNaSAL and CSAL are the product concentrations of soluble salicylate and crystals, respectively. Ceq is the equilibrium (interfacial) concentration of salicylate, which was ~2.2 g/L over the temperature range used in this demonstration.

The yield was defined on a feed basis as:

(7)

(7)

And on a product-only basis as:

(8)

(8)

If the % error in the mass balance on salicylate is large, then it is likely that either CSAL or CNaSAL are in error, as both are difficult to measure accurately. By looking at the values of Y1 and Y2 (at which gives a more reasonable trend), the primary source of the error can be determined.

From the values for G and B0, the powers "g" and "b" in Equation (4) were estimated using linear regression. Franck et al. reports a power "g" of ~3 and "b" of ~6 for this system11 using highly sterile conditions and high agitator speeds. Determining the differences between the experimental powers "g" and "b" and those of Franck et al. is useful in identifying factors that might be influencing the growth and nucleation functions. Representative data for a 50°C crystallization with feed concentrations of 0.35 M (NaSAL) and 0.25 M (H2SO4) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Crystallization Data

| Flow rate, mL/min | τ |  |

CNaSAL | CSAL | Y1 | Y2 | |

| NaSAL | H2SO4 | min | mm | mol/L | g/mL | % | % |

| 119 | 59.5 | 23.3 | 700 | 0.063 | 0.022 | 69 | 72 |

| 85 | 42.5 | 32.6 | 876 | 0.059 | 0.026 | 81 | 76 |

| 51 | 25.5 | 54.3 | 1190 | 0.055 | 0.026 | 81 | 77 |

These data were also used to solve for G and B0 and linear regression was performed to determine the powers "g" and "b" using the linearized Equation (4). Linear regression of the log functions (an example is shown in Figure 4) gave g = 1.1 and b = 2.4. While the trend in the powers (b about twice as large as g) was the same as observed in Franck et al., the powers themselves differed significantly, and the dependences on supersaturation ΔC were much smaller. This suggests that factors other than ΔC could be affecting the growth and nucleation rates, such as inadequate mixing, the relatively high pH's (for equimolar feeds the pH's are between 2.2-2.4), and ionic impurities introduced in the water (the municipal supply). These experimental powers would be used in any scale-up calculations, because other than ΔC, these factors would presumably be present in both the pilot-scale and industrial designs.

Figure 4. Linear regression of growth rate G as a function of supersaturation ΔC

Applications and Summary

This experiment demonstrated how to take raw concentration, flow and temperature measurements and use MSMPR theory to estimate the key parameters needed to design a large, complex crystallizer system. The critical role that residence time plays in obtaining high crystal yields and in controlling the average size of the crystals, was explored. Often there is an optimal residence time because very large crystals are seldom desirable. The same is true for mixing – mixing must be sufficient to keep the solid crystals from settling to the bottom, but at the same time the agitator speed is often a significant operating cost.

Some of the problems often experienced with this unit – partial blockages due to particle agglomeration, difficulties in obtaining uniform supersaturation due to imperfect mixing, and long times to reach steady state – are common to even well designed industrial crystallizers. This is why crystallizer designs seen in the manufacturers' literature are often amazingly complex.

This process is similar to crystallizations of other biologicals, such as L-ornithine-L-aspartate, which is used to treat chronic liver failure.5 The precursor L-ornithine hydrochloride costs >$300/kg and is difficult to recycle, so design for high crystal yields is critical. An example of an antisolvent, as opposed to pH-swing, biological crystallization is the refinement of danazol, a synthetic steroid used to treat endometriosis.13 Many drugs are hydrophobic with poor solubility in water. By dissolving the raw danazol product in ethanol and then re-crystallizing it by mixing with water, a purer and smaller particle size crystal product can be obtained. Crystallization of proteins is another important application, one example being lysozyme production.14

Industrial crystallizers can be designed to produce very narrow crystal size distributions through the application of fines removal (e.g., a pumparound heat exchanger that slightly raises temperature to dissolve the smallest crystals) and size classification (e.g., an "elutriation leg" that separates particles on the basis of their terminal velocities, collecting only the largest in the population). These design concepts were developed for inorganic salt crystallization but are now moving into the biological realm.

Materials List

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Agitator, 150 W | Caframo | BDC 3030 | on reactor |

| Circulating heater | Neslab | RTE 110 | 0-100°C, for reactor |

| Peristaltic pumps (2) | Cole-Parmer | Masterflex L/S 7550-60, 1.6-100 rpm, 0.1 hp | For both NaSAL and H2SO4 feeds |

| Centrifugal pump | Cole-Parmer | 7553-00, 6-600 rpm | For product recycle |

| UV-Vis spectrophotometer | Ocean Optics | USB 2000 | For soluble NaSAL analysis |

| UV-Vis power supply | Ocean Optics | DT1000 CE | For use with USB 2000 |

APPENDIX A – USING THE SPECTROMETER

- Open the SpectraSuite software. Switch on both the UV and VIS lamps on the source. Be sure to turn the lamps off after using. Set the acquisition mode to Scope (blue S button on toolbar).

- On the toolbar change the Integration Time a 250 ms, the Scans to Average a 25, and the Boxcar Width a 2. Check the boxes for Strobe/Lamp Enable, Electric Dark Correction, and Stray Light Correction.

- Prepare Dark Spectrum and Reference Spectrum files. The spectrometer requires the generation of a Dark Spectrum file and a Reference Spectrum file.

- Immerse the probe into a test tube filled with DI water.

- To create a Dark Spectrum file, unplug the probe from the light source (white box). The graph should nearly trace the x-axis. To save your newly created Dark Spectrum, click on the grey light bulb, then File -> Store -> Store Dark Spectrum.

- To create a Reference Spectrum file, plug the probe connection back into the light source. Some peaks should appear on the graph in SpectraSuite. To save this Reference Spectrum, click on the yellow light bulb, then File -> Store -> Store Reference Spectrum.

- If ANY settings are changed (e.g., Integration Time, etc.), both the Dark Spectrum and Reference Spectrum must be generated again.

- Switch from Scope a Absorbance (A) mode. For NaSAL solutions, the absorbance should be observed at ~300 – 330 nm.

Quantification is only possible if NaSAL/salicylic acid solutions follow the Beer-Lambert law (A is in the “linear region”). For the salicylate ion, this region is A < ~0.9 – 1. Given past results, this criterion suggests that NaSAL solutions MUST be diluted (with DI water) to 0.05 g/L or less for quantification. Then, the unknown solutions can be quantified by comparing to the absorbance of an appropriately diluted standard solution:

where C is concentration, A absorbance, “u” an unknown, and “s” a standard solution of NaSAL. Note that BOTH “u” and “s” must show absorbance inside the linear range.

In spectroscopy, the absorbance depends on two factors, the type of chemical and its concentration, and the path length in the fluid. Change the concentration by dilution.

Referencias

- C. Wibowo, L. O’Young and K.M. Ng, Chem. Eng. Prog., Jan. 2004, pp. 30-39.

- W.J. Genck, Chem. Eng. Prog., Oct. 2004, pp. 26-32.

- S. Takamatsu and D.D.Y. Ryu, Biotechnol. Bioeng., 32, 184-191 (1988).

- F. Wang and K.A. Berglund, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 39, 2101-2104 (2000).

- Y. Kim, S. Haam, Y.G. Shul, W.-S. Kim, J.K. Jung, H.-C. Eun and K.-K. Koo, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 42, 883-889 (2003).

- K. Hussain, G. Thorsen and D. Malthe-Sorenssen, Chem. Eng. Sci., 56, 2295-2304 (2001).

- H. Gron, A. Borissova and K.J. Roberts, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 42, 198-206 (2003).

- F. Lewiner, G. Fevotte, J.P. Klein and F. Puel, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 41, 1321-1328 (2002).

- For example: W.L. McCabe, J.C. Smith, and P. Harriott, “Unit Operations of Chemical Engineering”, 7th Ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2005, Ch. 27, or C.J. Geankoplis, “Transport Processes and Unit Operations”, 3rd Ed., 1993, Ch. 12.

- P. Barrett, Chem. Eng. Prog., Aug. 2003, pp. 26-32.

- R. Franck, R. David, J. Villermaux and J.P. Klein, Chem. Eng. Sci., 43, 69-77 (1988).

- J. Garside, Chem. Eng. Sci., 40, 3-26 (1985).

- H. Zhao, J.-X. Wang, Qi-An Wang, J.-F. Chen and J. Yun, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 46, 8229-8235 (2007).

- J.S. Kwon, M. Nayhouse, G. Orkoulas and P.D. Christofides, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 53, 15538-15548 (2014).

Transcripción

Industrial crystallization is applied for the separation and purification of compounds and mixtures. In order to design economical systems, various parameters have to be studied. Crystallization is used for the separation of chiral compounds and amino acids, or for purification of antibiotics, food additives and agrochemical compounds. Different means of crystallization include cooling, chemical modification, evaporation or pH swing. A crystallizer can be used to investigate key parameters affecting crystal development, such as cooling and rates or supersaturation. With the microscope, the crystal size and morphology can be monitored and dependencies of various factors observed. In this experiment, sodium salicylate is reacted with sulfuric acid, leading to precipitation of salicylic acid, which is a precursor of Aspirin. Samples are analyzed by UV vis, a gravimetric analysis and microscopy. This video will illustrate the concept, analysis and application of a crystallizer unit.

For a scale up of a crystallizer, it is important to estimate key parameters. These can be studied using an MSMPR unit. Although industrial crystallizers really behave like MSMPRs, the concept is still relevant for bench and pilot scale units. The MSMPR crystallizer is analogous to a continuous, stirred-tank reactor. It assumes perfect mixing of solid and liquid phases. MSMPRs are used to assess key crystallization parameters, such as the crystal nucleation rate, which is also known as the birth function and the crystal growth rate. The nucleation is catalyzed by existing crystals and solid surfaces such as the walls of the reactor. The general population balance model for a MSMPR crystallizer yields the number density N of the crystals, which is a probability density with respect to L, the primary crystal dimension. In an MSMPR, the number distribution is predicted to be an exponential distribution. The birth function and growth rate can be determined using the zeroth and first moments of this distribution. Most importantly, they can also be related to the supersaturation, which is the mass transfer driving force in crystallization, and which is, in turn, dependent on agitation rate and temperature. For a constant temperature and agitator speed, both the birth function and growth rate are directly related to supersaturation, and the powers B and G can be determined by linear regression. According to the MSMPR model, the number density of crystals decreases exponentially with length. A deviation from the exponential distribution would imply imperfect mixing of solids or liquids. In industrial applications, relatively narrow Gaussian distributions of crystal sizes are required, rather than exponential ones. Nevertheless, the MSMPR model is still useful, particularly in pilot plants, as it enables determination of growth and birth rates as well as the degree of supersaturation from raw data. Now that you are familiar with the MSMPR model, let’s apply the concept to the experiment.

Wear proper PPE when handling sodium salicylate and sulfuric acid solutions. Write down the basic physical properties of the salicylic acid for later use. Before your start, familiarize yourself with the crystallization system. The apparatus consists of two feed tanks, variable speed pumps, a five liter crystallizer-stirred tank, a circulating bath for temperature control, power controller, product tank and a make-up tank for feed regeneration, using a sodium hydroxide solution. The system is operated using a distributed control system and a graphical interface, from which valves can be operated to control the temperature and flow. A schematic output providing trends of flow rate and temperature is also available.

Check that all continuous controllers are set to the manual mode, and that all solenoid valves are either in the closed, two-way or in the recycle, three-way mode. Make sure the crystallizer is full with water and some salicylic acid slurry to the overflow level of approximately 4.15 liters, as indicated on the stirred tank. Add water and salicylic acid using the addition port if tank is not full. Turn on the agitator for the crystallizer and the thermostated bath and pumps. Set the temperature controller for the bath temperature to auto, and the set point to the desired temperature, usually approximately 53 degrees Celsius for a 50 degree Celsius crystallizer. Set the pump speeds to give approximately 25 to 35 milliliters per minute for the acid solution. For the sodium salicylate, the flow rate is determined by stoichiometric equivalents. Using the known feed concentrations, set the flow rates for stoichiometric equivalents. Make sure that the product tank is not full and the drain valve is closed. Then, turn on the spectrometer, and use a provided link in the control console to check that communication between the apparatus is established.

Switch to feed mode on both three-way valves. This sets time zero for an experiment. Periodically check the overflow line for any blockage. Use a piece of steel tubing to remote the line entering the product tank using the hole provided if blockage is detected. After one hour, use a wide-mouthed pipette and insert it into the sample port of the crystallizer. Collect enough sample to fill enough five pre-weighed 15 milliliter centrifuge or test tubes. Take two sets of samples 10 to 15 minutes apart. Vary the volumetric flow rates to control TOW and adjust for two other widely-spaced residence times. Maintain the stoichiometric equivalents and collect samples as before. When finished, set the pump output to zero per cent, the three-way valves to recycle. Return the temperature controller to manual at zero per cent output and shut off the pumps, agitators and thermostated bath.

The salicylate ion concentration can be determined using UV vis and the solid salicylic acid concentration can be determined gravimetrically as kilograms per meter cubed slurry. Before the analysis, first centrifuge samples for five minutes and decant the liquid. Record the total volume of sample retrieved. Combine the liquid samples from a given set and dilute by 50 to 100 times. For the liquid, measure the absorbance of the sodium salicylate and the salicylic acid using the UV vis spectrometer. The absorbance is assumed to be additive, since the same chromophore is detected for both samples. For the gravimetric determination, use the solids remaining in the centrifuge or test tubes. Dry the tubes upright in the convection oven at 70 degrees Celsius for two days. Then reweigh the cooled test tubes to determine the weight of the crystals and the concentration in kilograms per liter. Lastly, using a microscope, determine the length distribution of the needle-shaped salicylic acid crystals.

Compute the solid crystal concentration for all runs via the gravimetric method. Generate a mass balance on salicylate. Then, calculate the supersaturation and residence time. Next, determine the crystal yields on a feed and product basis, using the moles of the product, feed, and the dissolved salicylate product. Use the crystal concentration, crystal dimension, and residence time to solve for the birth function and growth rate. Then estimate the powers G and B through linear regressions of the log functions. Here is an example of a crystallization at 50 degrees Celsius. The power of B is twice as large as G, indicating that supersaturation is affecting the birth rate more than the growth rate. These powers would be used for scale up if supersaturation is unchanged. Comparisons to other experiments can identify factors that influence the growth and birth functions, such as inadequate mixing, pH and ionic impurities in the make up water.

Industrial crystallization is widely applied in pharmaceutical, chemical and food-processing industries for separation and purification of various compounds. Danazol is synthetic steroid which is used for the treatment of endometriosis. As with many other pharmaceutical compounds, Danazol is hydrophobic and poorly soluble in water. Therefore, the raw Danazol product is initially dissolved in ethanol and then recrystallized by mixing it with some water, which produces pure, small particle sized product crystals. Industrialized crystallizers can be used in the production of lysosomes. The apparatus can be designed to produce a very narrow crystal sized distribution through the application of a pump around heat exchanger, which slightly raises the temperature to dissolve the smallest crystals. The size distribution can be regulated by separating the crystal particles on the basis of their terminal velocities. This concept also finds application in the crystallization of inorganic salts.

You’ve just watched Jove’s introduction to industrial crystallization. You should now understand the MSMPR crystallizer model, how to operate the crystallization unit and how to analyze the results. Thanks for watching.