Cardiac Exam III: Abnormal Heart Sounds

88,287 Views

•

•

概述

Source: Suneel Dhand, MD, Attending Physician, Internal Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

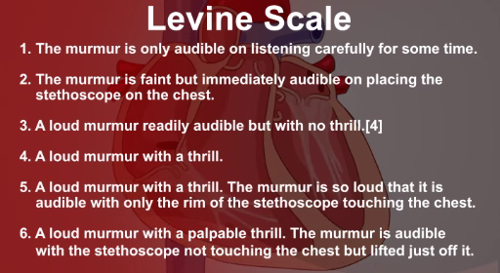

Having a fundamental understanding of normal heart sounds is the first step toward distinguishing the normal from the abnormal. Murmurs are sounds that represent turbulent and abnormal blood flow across a heart valve. They are caused either by stenosis (valve area too narrow) or regurgitation (backflow of blood across the valve) and are commonly heard as a "swishing" sound during auscultation. Murmurs are graded from 1 to 6 in intensity (1 being the softest and 6 the loudest) (Figure 1). The most common cardiac murmurs heard are left-sided murmurs of the aortic and mitral valves. Right-sided murmurs of the pulmonary and tricuspid valves are less common. Murmurs are typically heard loudest at the anatomical area that corresponds with the valvular pathology. Frequently, they also radiate to other areas.

Figure 1. The Levine scale used to grade murmur intensity.

In addition to the two main heart sounds, S1 and S2, which are normally produced by the closing of heart valves, there are two other abnormal heart sounds, known as S3 and S4. These are also known as gallops, because of the "galloping" nature of more than two sounds in a row. S3 is a low-pitched sound heard in early diastole, caused by blood entering the ventricle. S3 is a sign of advanced heart failure, although it can be normal in some younger patients. S4 is heard in late diastole and represents ventricular filling due to atrial contraction in the presence of a stiff ventricle. S4 is also heard in heart failure and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Procedure

1. Murmurs

- Position the patient at a 30- to 45-degree angle on the examination table.

- When auscultating a murmur, ask the patient to breathe in and out, as it can provide a vital diagnostic clue. Right-sided murmurs (pulmonary and tricuspid) are best heard on inspiration, as blood flows into the right ventricle when intrathoracic pressure decreases. Conversely, left-sided murmurs are heard best on expiration.

- Categorize murmurs according to the following criteria: intensity (loudness), pitch (e.g., high or low, harsh or blowing), configuration (e.g., crescendo-decrescendo), location, and timing in the cardiac cycle (e.g., early systolic/diastolic).

- Remember that not all murmurs are abnormal, and that systolic murmurs can be benign in younger people.

- Also remember that each murmur is usually loudest at the anatomical area that corresponds with the valvular pathology.

- Aortic stenosis: Auscultate with the diaphragm of the stethoscope on the aortic area, with the patient in supine position. Aortic stenosis is a harsh-sounding ejection systolic or crescendo-decrescendo murmur that occurs during systole, as the blood passes across the stenotic aortic valve. This murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and can be heard in the carotid area of the neck.

- Aortic regurgitation: Auscultate with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border, close to the tricuspid area, with the patient leaning forward. The murmur of aortic regurgitation is a soft-blowing early diastolic decrescendo murmur. It can be associated with a number of other physical examination findings (described in step 5 below).

- Mitral regurgitation: Place the diaphragm of the stethoscope on the mitral area. This murmur is a blowing pansystolic (or holosystolic) murmur. It classically radiates toward the axilla. Mitral valve prolapse can also be associated with a "mid-systolic click" sound.

- Mitral stenosis: Auscultate with the bell of the stethoscope in the mitral area. It is a low-frequency rumbling mid-diastolic murmur and can be accentuated by laying the patient on his/her left side. Mitral stenosis is a very rare murmur that is almost always the result of prior rheumatic fever.

- Right-sided murmurs: Remember that murmurs associated with the tricuspid and pulmonary valves are rare. Pulmonary stenosis, tricuspid regurgitation, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy manifest as systolic murmurs. Tricuspid regurgitation occurs in association with longstanding lung disease, such as emphysema or pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary regurgitation and tricuspid stenosis are diastolic murmurs. Congenital heart disorders, such as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), can also cause loud murmurs. In the case of PDA, a continuous "machinery-like" murmur is auscultated.

2. Gallops (S3 and S4)

- Auscultate for S3 and S4 in the mitral and tricuspid areas with the bell of the stethoscope pressed lightly on the patient's chest, and the patient lying on his/her left side.

3. Splitting of heart sounds:

The second heart sound can be "split" when the closure of the aortic and pulmonary valves do not occur together. The splitting of S2 during inspiration is normal and is known as physiological splitting (P2 occurs after A2). Fixed splitting can be heard with an atrial septal defect. If the splitting occurs during expiration, it is known as paradoxical splitting, which occurs when there is a prolonged left ventricular phase, such as in left bundle branch block or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

- Ask the patient to breathe in and out, and auscultate over the second intercostal space at the left sternal edge.

- Note at which phase of respiratory cycle the splitting occurs.

4. Rubs:

A pericardial friction rub, as seen in pericarditis, resembles a rubbing sound of two surfaces rubbing or grating against each other.

- Auscultate at the lower left sternal edge with the patient leaning forward.

5. Note if the following signs of valvular pathology are present:

- Quincke's pulse: seen in aortic regurgitation, resulting in alternating blanching and flushing of the nail bed.

- Corrigan's pulse, also known as Watson's water hammer pulse: a collapsing pulse that occurs in aortic regurgitation.

- de Musset's sign: a "bobbing" movement of the head, as seen with aortic regurgitation.

- Blood pressure: a small gap between the systolic and diastolic blood pressure (narrow pulse pressure), frequently found in aortic stenosis. A wide pulse pressure is characteristic of aortic regurgitation.

Having a fundamental understanding of normal and abnormal heart sounds is the first step toward distinguishing between them. Murmurs and gallops present two broad categories of abnormal heart sounds. Murmurs are sounds that represent turbulent and abnormal blood flow across a heart valve. On the other hand, gallops refer to the occurrence of more than two heart sounds in a row.

In this video, we’ll first review the phonocardiograms of, and the mechanism behind different abnormal heart sounds. Then, we’ll discuss the auscultation landmarks and the essential steps useful for identifying underlying cardiac pathologies

Murmurs are caused either by stenosis, that is valve area narrowing, or due to regurgitation, which refers to the backflow of blood across a valve. However, not all murmurs are pathological; systolic murmurs can be benign in younger people.

All murmurs are categorized according to the intensity or loudness, pitch-high or low, harsh or blowing, configuration-crescendo decrescendo, location, and timing in the cardiac cycle-systolic or diastolic. The murmur intensity is graded from 1 to 6 on the Levine scale, 1 being the softest referring to the murmur only audible on listening carefully for some time, and 6 refers to the loudest murmur with a palpable thrill, which is audible with the stethoscope not touching the chest but lifted just off it.

The most common cardiac murmurs heard are the left-sided murmurs of the aortic and mitral valves. Aortic stenosis is a harsh-sounding, systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur that sounds like this… This murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and can be heard in the carotid area of the neck. The murmur of aortic regurgitation is a soft-blowing, early diastolic, decrescendo murmur; take a listen… On the other hand, mitral regurgitation is a blowing, pansystolic or holosystolic murmur that sounds like this… This murmur usually radiates towards the axilla. Lastly, mitral stenosis produces a low frequency, rumbling, and mid-diastolic murmur… The right-sided murmurs, which are related to the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, are rare. Additionally, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is a genetic disorder leading to an abnormal thickening of the cardiomuscular wall, produces a systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur… Likewise, Patent Ductus Arteriosus-a congenital heart disorder in which the ductus arteriosus does not close-induces a continuous machine-like murmur…

Except murmurs, other atypical heart sounds include gallops S3 and S4. This is the S3 gallop…which is a low-pitched sound, heard in early diastole, caused by blood entering the ventricle. Whereas S4, which sounds like this…is heard in late diastole, and represents ventricular filling due to atrial contraction in the presence of a stiff ventricle. S3 is a sign of advanced heart failure, although it can be normal in some younger patients. And S4 is also heard in heart failure and in presence of left ventricular hypertrophy.

In addition to murmurs and gallops, splitting of normal heart sounds may occur. Each normal heart sound-S1 and S2-is composed of two components referring to the closing of the two valves, which make up that sound. Therefore, S1 is composed of tricuspid T1 and mitral M1 components. Similarly, S2 is composed of aortic A2 and pulmonary P2 elements. It’s hard to distinguish between the sounds produced by individual valves, as they close almost together. But if the pair of valves is not closing together, then a “split” might appear on auscultation.

S2 split during inspiration that sounds like this…is normal. It is referred to as the “physiological” split. However, if S2 split occurs during expiration, it called “paradoxical” split…which occurs when there is a prolonged left ventricular phase, such as in left bundle branch block or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. And if the split occurs throughout the respiratory cycle, then it is known as “fixed” split…which can be heard in case of an atrial septal defect.

The last abnormal heart sound that we’ll discuss is a result of pericarditis, which refers to inflamed pericardium. The sound is known as the “friction rub”, which occurs due to the rubbing of the inner and outer pericardium layers against each other

Now that we have reviewed the normal and abnormal heart sounds, let’s discuss the auscultation steps essential to distinguish them from one another. Remember, each murmur is usually heart loudest at the anatomical area that corresponds to the valvular pathology

When auscultating to specifically diagnose a murmur, ask the patient to breathe in and out deeply, as the murmur timing in the respiratory cycle can provide a vital diagnostic clue. Start by placing the diaphragm in the aortic area to detect murmur due to aortic stenosis. If present, auscultate the carotid area as this murmur classically radiates to this neck region. Always listen for at least 5 seconds to ensure that you’re not missing any subtle sounds. To detect murmur due to aortic regurgitation, request the patient to lean forward. Remind the patient to breath in and out constantly. Now, using the diaphragm, auscultate at the lower left sternal border, close to the tricuspid area. This is done to accentuate the murmur of aortic regurgitation. In the same position, if pericarditis is present, you might encounter sounds due to the friction rub.

Next, request the patient to lie back and using the diaphragm, listen to the sound in the mitral area to identify mitral regurgitation. If present, move the stethoscope laterally to confirm radiation to the axilla. In addition, using the bell of the stethoscope, auscultate the mitral area to check for the presence of mitral stenosis. Subsequently, using the diaphragm auscultate the pulmonic area. Here, you can clearly distinguish the second heart sound and sometimes you may hear the S2 split. Note at which phase of respiratory cycle the splitting occurs, as this can help in classifying the split as physiological, paradoxical or fixed. In addition, you may encounter the systolic murmur due to pulmonary stenosis or a diastolic one due to pulmonary regurgitation.

Next, auscultate the tricuspid area. Here, similar to the pulmonic area, you may come across the murmurs associated with tricuspid regurgitation and stenosis, which are systolic and diastolic in nature, respectively. Next, instruct the patient to lie on their left side and with the bell pressed lightly on the patient’s chest, auscultate in the mitral and the tricuspid area. In this position, you might hear the murmur of mitral stenosis, as well as the galloping S3 and S4 sounds.

Additionally, if you suspect hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, then using the diaphragm, auscultate between the apex and left lower sternal border. If you hear a systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur in this area then you should request the patient to sit straight and perform the Valsalva maneuver. One of the ways to this is by asking the patient to blow out with mouth closed. This maneuver is known to accentuate the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated murmur. Furthermore, if the rare patent ductus arteriosus or PDA is suspected, then auscultate the upper left chest region to listen for the characteristic continuous machine-like murmur.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on cardiac auscultation highlighting the abnormal heart sounds. In this video, we reviewed the phonocardiograms of commonly encountered abnormal heart sounds and the pathology behind their occurrence. We also highlighted the important steps that every physician should perform during cardiac auscultation so that the presence of abnormal sounds does not go undetected. As always, thanks for watching!

Applications and Summary

The ability to recognize and distinguish between the different cardiac murmurs develops with time and practice. The first step is to identify normal from abnormal. When a murmur is heard, an examiner should think about the following questions: What part of the cardiac cycle does it occur in – systolic or diastolic? Where is the murmur loudest? Where does the murmur radiate to? Is it loudest on inspiration or expiration?

An examiner should make sure the environment is quiet and that there is ample time to hear the murmur. Loud murmurs are often heard across the precordium, in which case, ascertaining where it is loudest and where it radiates to is crucial. Whenever a murmur is heard, the clinician should get into the habit of going through this systematic approach in order to correctly diagnose the underlying pathology.

成績單

Having a fundamental understanding of normal and abnormal heart sounds is the first step toward distinguishing between them. Murmurs and gallops present two broad categories of abnormal heart sounds. Murmurs are sounds that represent turbulent and abnormal blood flow across a heart valve. On the other hand, gallops refer to the occurrence of more than two heart sounds in a row.

In this video, we’ll first review the phonocardiograms of, and the mechanism behind different abnormal heart sounds. Then, we’ll discuss the auscultation landmarks and the essential steps useful for identifying underlying cardiac pathologies

Murmurs are caused either by stenosis, that is valve area narrowing, or due to regurgitation, which refers to the backflow of blood across a valve. However, not all murmurs are pathological; systolic murmurs can be benign in younger people.

All murmurs are categorized according to the intensity or loudness, pitch-high or low, harsh or blowing, configuration-crescendo decrescendo, location, and timing in the cardiac cycle-systolic or diastolic. The murmur intensity is graded from 1 to 6 on the Levine scale, 1 being the softest referring to the murmur only audible on listening carefully for some time, and 6 refers to the loudest murmur with a palpable thrill, which is audible with the stethoscope not touching the chest but lifted just off it.

The most common cardiac murmurs heard are the left-sided murmurs of the aortic and mitral valves. Aortic stenosis is a harsh-sounding, systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur that sounds like this… This murmur classically radiates to the carotid arteries and can be heard in the carotid area of the neck. The murmur of aortic regurgitation is a soft-blowing, early diastolic, decrescendo murmur; take a listen… On the other hand, mitral regurgitation is a blowing, pansystolic or holosystolic murmur that sounds like this… This murmur usually radiates towards the axilla. Lastly, mitral stenosis produces a low frequency, rumbling, and mid-diastolic murmur… The right-sided murmurs, which are related to the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, are rare. Additionally, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is a genetic disorder leading to an abnormal thickening of the cardiomuscular wall, produces a systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur… Likewise, Patent Ductus Arteriosus-a congenital heart disorder in which the ductus arteriosus does not close-induces a continuous machine-like murmur…

Except murmurs, other atypical heart sounds include gallops S3 and S4. This is the S3 gallop…which is a low-pitched sound, heard in early diastole, caused by blood entering the ventricle. Whereas S4, which sounds like this…is heard in late diastole, and represents ventricular filling due to atrial contraction in the presence of a stiff ventricle. S3 is a sign of advanced heart failure, although it can be normal in some younger patients. And S4 is also heard in heart failure and in presence of left ventricular hypertrophy.

In addition to murmurs and gallops, splitting of normal heart sounds may occur. Each normal heart sound-S1 and S2-is composed of two components referring to the closing of the two valves, which make up that sound. Therefore, S1 is composed of tricuspid T1 and mitral M1 components. Similarly, S2 is composed of aortic A2 and pulmonary P2 elements. It’s hard to distinguish between the sounds produced by individual valves, as they close almost together. But if the pair of valves is not closing together, then a “split” might appear on auscultation.

S2 split during inspiration that sounds like this…is normal. It is referred to as the “physiological” split. However, if S2 split occurs during expiration, it called “paradoxical” split…which occurs when there is a prolonged left ventricular phase, such as in left bundle branch block or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. And if the split occurs throughout the respiratory cycle, then it is known as “fixed” split…which can be heard in case of an atrial septal defect.

The last abnormal heart sound that we’ll discuss is a result of pericarditis, which refers to inflamed pericardium. The sound is known as the “friction rub”, which occurs due to the rubbing of the inner and outer pericardium layers against each other

Now that we have reviewed the normal and abnormal heart sounds, let’s discuss the auscultation steps essential to distinguish them from one another. Remember, each murmur is usually heart loudest at the anatomical area that corresponds to the valvular pathology

When auscultating to specifically diagnose a murmur, ask the patient to breathe in and out deeply, as the murmur timing in the respiratory cycle can provide a vital diagnostic clue. Start by placing the diaphragm in the aortic area to detect murmur due to aortic stenosis. If present, auscultate the carotid area as this murmur classically radiates to this neck region. Always listen for at least 5 seconds to ensure that you’re not missing any subtle sounds. To detect murmur due to aortic regurgitation, request the patient to lean forward. Remind the patient to breath in and out constantly. Now, using the diaphragm, auscultate at the lower left sternal border, close to the tricuspid area. This is done to accentuate the murmur of aortic regurgitation. In the same position, if pericarditis is present, you might encounter sounds due to the friction rub.

Next, request the patient to lie back and using the diaphragm, listen to the sound in the mitral area to identify mitral regurgitation. If present, move the stethoscope laterally to confirm radiation to the axilla. In addition, using the bell of the stethoscope, auscultate the mitral area to check for the presence of mitral stenosis. Subsequently, using the diaphragm auscultate the pulmonic area. Here, you can clearly distinguish the second heart sound and sometimes you may hear the S2 split. Note at which phase of respiratory cycle the splitting occurs, as this can help in classifying the split as physiological, paradoxical or fixed. In addition, you may encounter the systolic murmur due to pulmonary stenosis or a diastolic one due to pulmonary regurgitation.

Next, auscultate the tricuspid area. Here, similar to the pulmonic area, you may come across the murmurs associated with tricuspid regurgitation and stenosis, which are systolic and diastolic in nature, respectively. Next, instruct the patient to lie on their left side and with the bell pressed lightly on the patient’s chest, auscultate in the mitral and the tricuspid area. In this position, you might hear the murmur of mitral stenosis, as well as the galloping S3 and S4 sounds.

Additionally, if you suspect hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, then using the diaphragm, auscultate between the apex and left lower sternal border. If you hear a systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur in this area then you should request the patient to sit straight and perform the Valsalva maneuver. One of the ways to this is by asking the patient to blow out with mouth closed. This maneuver is known to accentuate the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated murmur. Furthermore, if the rare patent ductus arteriosus or PDA is suspected, then auscultate the upper left chest region to listen for the characteristic continuous machine-like murmur.

You’ve just watched JoVE’s video on cardiac auscultation highlighting the abnormal heart sounds. In this video, we reviewed the phonocardiograms of commonly encountered abnormal heart sounds and the pathology behind their occurrence. We also highlighted the important steps that every physician should perform during cardiac auscultation so that the presence of abnormal sounds does not go undetected. As always, thanks for watching!